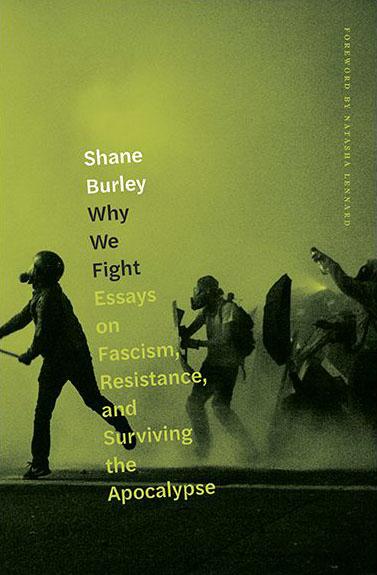

The following is an excerpt from Shane Burley’s 2021 book, Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse.

Over the last six years, the U.S. has seen a mass wave of nativism that has shifted the “Overton Window” of acceptable politics, making once-marginal aspects of anti-immigrant ideology a part of the mainstream GOP. This has changed the nature of politics, bringing the underlying consequences of colonialism and White supremacy to the surface and mobilizing a militant force against progress, both on the ground and in the halls of power. And it’s led to something else as well: the transformation of antifascism into a mass movement.

Prior to 2015, “antifa” was one of those radical brands you’d mostly see on t-shirts at anarchist book fairs, like Earth First! or the Industrial Workers of the World, but it was hardly a household name beyond those circles. Moreover, it was one of the movements least likely to raise eyebrows—it was Nazis they were fighting, after all. But over the last half-decade, antifascism has moved far past being a subculture and has become an intersecting movement with different strains, strategies, cultures, tactics, identities, and personalities. Instead of being a unitary movement it is a mass mobilization that converges on its one purpose: to stop fascism dead.

Antifascism called into question what most European and American countries said they were: publicly opposed to inequality and celebrating democracy, at the same time that White identity extended the violence of colonialism into modernity. Now everyone has a hand in fighting fascism, with groups popping up around the country, some using the “antifa” branding, some going with larger non-profits, and all finding a certain common language in the mass action. The Trump presidency brought the return of massive, city shuttering, street-blocking protests, from the Women’s March, to anti-Trump mobilizations, to the fight against racist police violence in 2020. These are all under the banner of antifascism, implicitly or explicitly, but it made sense to almost everyone because the impending threat of fascism was no longer ephemeral. People were collectively responding, not only to the seemingly impulsive violence of small White nationalist groups, but also to the massive growth of Trumpism as a street-level movement with violent potential; the growth of massive far-right organizations training for war; and a potentially captured state set on border imperialism, mass incarceration, and the validation of White supremacy.

Even more, “antifa” itself became a buzzword, and less for what the term actually meant and more because of the fears right-wing pundits could place on it. Thanks to far-right grifters like Andy Ngo and Tucker Carlson, the word “antifa” has been divorced from its meaning (militant antifascist organizing) and has now become the default word for all left-wing protests with an antiracist edge. Black Lives Matter, labor actions, mutual aid networks, immigration protesters, and abortion clinic defense have now all been painted as “antifa,” and antifa is a proxy for every fear that the Right has conjured up about what an insurgent Left is capable of.

The violence of the Right—itself a lethal pandemic that touches all of our lives—is reframed as self-defense when paired with a hollowed-out image of antifa. Reality has become malleable, and just as “Fake News” stole our shared understanding of events, so has edited video footage, viral tweets, and dishonest testimonials. Antifa is everywhere and nowhere, simultaneously bringing down society and composed of nothing but lazy millennials. Antifa is now a stand-in for every cultural trend the Right finds frightening. This would be ridiculous if it didn’t have such dire consequences, as senators and attorneys general vie to label antifascism as terrorist criminality, potential prosecutions become a viable threat, and the Far Right is egged on to murderous attacks.[1]

“At this moment the people are a real threat to their power and they’re desperate to discredit the movement because it’s growing and spreading so rapidly they can’t contain it,” says Effie Baum, an organizer with the antifascist group PopMob.[2]

Given the public perception and stigma that already exists against antifascists, we are an easy scapegoat. This scapegoating also works to create division between those who are outraged by police violence but may choose different tactics to show it. An authoritarian administration is always going to villainize those most opposed to the rising tide of fascism in the U.S. and internationally. By shifting the narrative away from police brutality and the rampant murder of Black and brown people by police, they can get public support from both sides fretting over broken windows, instead of focusing on the brutal police violence that we’ve seen over the last few years or the countless murders of Black men and women like George Floyd.[3]

Antifascists spent the years after 2016 fighting off accusations and innuendo, and the directionless attacks only expanded to journalists, politicians, community leaders, and the clergy. No one was spared from being discredited as another “antifa,” putting them outside the bounds of polite company. This labeling happened while antifascist groups continued to grow and meet the Far Right in event after event, even after absurd lawsuits and baseless criminal investigations attempted to dull their effectiveness. “Our community stands up to protect those who are targeted by White nationalists,” said David Rose (not his real name) of Rose City Antifa in Portland, Oregon. “In this unity comes the only sure defense against fascism and similarly violent nationalist ideologies. As a community, we need to say that this is unacceptable, that we will not allow immigrants, minorities, and activists to be attacked in our city.”[4]

To see antifascism—from liberal NGOs to radical groups—come to the forefront, for antifascism to become the default language for any mass resistance to the politics of this moment, is significant. Antifascism is a core response to the interrelated crises we currently face, from economic to ecological, which are crushing working class communities across the globe, and which are now defined in the mass consciousness as laced with fascist potential. The implicit understanding is that, as these crises deepen, the threat of fascism will as well, and all intersecting social movements will have to reckon with it. The “all hands on deck” approach will persist because there can be no success while the threat looms, and it is not going away anytime soon. Economic instability, the response from landlords and bosses as working people organize, the absolute decimation of wild lands… all of it is assumed to have fascism stamped on top of it as we have seen how capital will use nationalism to protect its interests.

Antifascism is the stopgap to very real and potential outcomes of the current crisis. To curb the crisis, to fight back against the destruction of our communities, to imagine a different future—these are now being recognized as requiring some degree of antifascism. There is no vibrancy without it, no grand vision of a different world is realistic without the awareness that defense against their preferred future is necessary. Crisis breeds the “mobilizing passions” to turn this way or that, towards one radical solution or another, and it requires an intervention to stop the borders and nativism from becoming the result.[5] Fascism is the worst possible scenario. It’s an approach to crisis that intervenes on the most catastrophic features of humanity, a false promise (prophet) that will lead to a perversion of peace and reconciliation. This crisis is an End Times narrative of its own, a kind of millennialism, as entire generations reckon with the fact that widespread fascism could become our reality. We are all millennialists now.

Antifascism is now the language we use to confront this tidal wave of misery. This “final battle” is now phrased in the most black and white of terms—us versus them—because fascism looks to transform diverse intersecting communities into tribal allegiances bent on confronting one another in desperate battle. If the apocalypse is now defined by fascism, our survival is built on antifascism, our ability to stave off the worst outcomes so something new is possible in its stead. This presents a strange challenge to antifascism then, to not just be a resistance to a possible future, but to be a future in its own right.

Endnotes

- Shane Burley, "The Right Wing Is Trying to Make It a Crime to Oppose Fascism," Truthout, April 9, 2019, truthout.org/articles/the-right-wing-is-trying-to-make-it-a-crime-to-oppose-fascism/.

- Author interview with Effie Baum, May 31, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Author interview with David Rose, August 13, 2019.

- Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Vintage Books, 2004), 41.