This April, Fox News’s Tucker Carlson elevated a narrative that has long festered on the Far Right to the conservative mainstream, when he used his show to promote the conspiratorial “Great Replacement” theory. That’s the idea that the so-called “radical Left” aims to change the racial or ethnic composition of the population through immigration, leaving White citizens and voters in the minority—in other words, “replaced.” In only slightly coded language, Carlson was promoting the same racist ideas as did the Unite the Right marchers in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, when they chanted in a torchlight parade, “Jews will not replace us.”[1]

After four years of Donald Trump and Stephen Miller’s malevolent war on migrants, more Americans are paying attention to the role of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies for mobilizing nativist or racist sentiments into a broad-based right-wing movement that aims to take political power. Although the mantra of a stolen election is a defining loyalty test for Trumpist Republicans, migration and the border remain among their principal lines of attack against the Biden administration as it attempts to reverse many of Trump’s most harmful policies.

But the U.S. is not alone in witnessing how far-right movements and parties exploit the global crisis of forced migration, as tens of millions of people flee violence, persecution, and extreme hardship, with millions seeking refuge and a livable life in the Global North.[2] Over the past five years, Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party has made dramatic gains, thanks largely to exploiting these tensions. Although the German Far Right has never been absent from the post-WWII political landscape, a new and more dangerous eruption occurred following Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis, to which the Far Right responded by inflaming anti-migrant and anti-Muslim fears and promoting ethno-cultural nationalism. Hate crimes and violence aimed at refugees and immigrants surged, alongside the AfD’s electoral successes, stunning the nation and challenging the popular belief that Germany had vanquished its racist-nationalist past. While far-right parties now contest power across Europe—and have won it in some Eastern European countries—what happens in Germany is a critical warning for the world about how migration can be exploited to rapidly shift the balance of power in a democratic state.[*]

Although the landscapes are different, there’s much that we in the U.S. can learn from what’s happening in Germany. Understanding the rhetorical stratagems of Germany’s Far Right—and how the country’s political leaders, parties and civil society have responded to it—is necessary as the U.S. confronts our own anti-migrant Far Right.[3]

War, Migration, and Angela Merkel’s Initial Welcome

By 2014, the catastrophic consequences for civilians of war and persecution in the Greater Middle East began to spill into Europe.[4] The ongoing civil war in Syria, along with the wars and repression in Afghanistan and Iraq, Yemen, Eritrea, South Sudan, and Congo, set off a flight for survival unseen in recent times. Syria alone suffered enormous casualties and the forced displacement of more than half of its pre-war population. Of those displaced, more than five million fled Syria to neighboring countries. Those who were able (about a million) pushed northward through Turkey and by small boats reached the nearby Greek islands.[5]

Greece’s left-wing government, which came into power in January 2015 and was struggling to overcome EU-imposed austerity measures, was in no position to accommodate the refugees. And so they moved northward over what came to be called the Balkan Route: through North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Austria. Despite extreme hardships and hostile, often violent government responses, most refugees pushed north toward potentially friendlier countries in hope of asylum, jobs, and housing. Their epic journey became an unfolding drama in the European media. In early 2015, two tragedies in the Mediterranean amplified the humanitarian crisis, as boats filled with migrants capsized, and hundreds of lives were lost. More disasters followed, leading Pope Francis and other European leaders to become more vocal: how could Europe stand by? By the summer of 2015, the “refugee crisis” and how to respond to it dominated public and political attention.[6]

Under growing pressure to act, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, leader of the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party, did something extraordinary. In late August 2015, she suspended the EU’s Dublin regulations, which stipulate asylum seekers must apply in the first country of arrival in the EU.[7] The suspension allowed Syrians—the largest group of refugees arriving in Europe in 2015[8]—to apply for asylum in Germany. A few days later, with thousands of refugees already crossing the German border, she announced her action to the nation, uttering the now famous phrase, “Wir schaffen das!” (“We can do this!”) Early that September, Germany temporarily opened its border with Austria, allowing tens of thousands of additional refugees to enter. These decisions and others would bring the total number of refugees entering Germany in 2015 to what has been widely reported as 1.1 million. (However, in September 2016 the German government claimed this number was inflated due to multiple registrations and revised the figure downward to 890,000.[9])

Merkel, while highly critical of other European governments for not sharing the humanitarian burden, asserted that Germany would step up to its moral responsibilities as a leader of a Europe committed to humanitarian principles. At the same time, she condemned the escalating anti-migrant violence occurring in eastern Germany and was emphatic that a clear line must be drawn against xenophobia and hatred.[10] Merkel’s decision included an outlay of billions of euros to provide emergency assistance and the promise to grant asylum to those who qualified.[11]

Some suggested that Merkel, the daughter of a pastor, was driven by religious and humanitarian instincts. Others emphasized that Merkel’s primary interest was in preserving the EU’s open borders policy. My research points to a more contextual explanation: that Merkel may have had Germany’s history and world image in mind. In contemporary Germany, the memory of the nation’s descent into fascism and responsibility for the Holocaust has become a vital part of civic and political culture.[12] In 2015, Germany’s then-President Joachim Gauck put it plainly: “There is no German identity without Auschwitz.”[13] Many Germans also understand that the universal human right of asylum, declared by the United Nations in 1948, was the direct result of Germany’s persecution of Jews, Roma, LGBTQ people, and others during the Third Reich. Many Germans had urged Merkel to act in recognition of this legacy, and when she did, her decision received broad public support, at least initially, with millions of volunteers offering their welcome with concrete acts of help across Germany.[14] Many others understood that an open response to the refugees was a rebuke to the anti-migrant violence that had already appeared in eastern German cities.

The “Refugee Crisis” and Far-Right Mobilization

Yet Merkel’s decision to allow the refugees into Germany was also controversial, sparking fierce opposition in the conservative media and among numerous politicians within Merkel’s CDU and the Christian Social Union (CSU), the center-right party in Bavaria aligned with the CDU. The CSU leadership, in particular, was critical, continuing that party’s longstanding practice of politicizing anti-immigrant anxieties and dispositions.[15] Germany had long been divided over immigration, dating back to the 1960s expansion of its “guest worker” program, which allowed some 750,000 mostly Turkish workers to move to Germany before the program ended in 1973. About half the Turkish workers remained in Germany and today “people of Turkish origin living in Germany” with their descendants now number about three million.[16]

The government’s initial unpreparedness was immediately observable and conservative critics were quick to draw attention to the real or imagined consequences of the sudden influx of refugees. Coverage in numerous media outlets became alarmist. The term “refugee crisis” took on a new meaning, shoving aside the earlier attention to the plight of the refugees: How could Germany absorb so many? Why weren’t other European governments doing more? How would the cost be paid for? Would Merkel’s generosity only encourage more to come? The criticisms mounted and by February 2016, a strong majority of those polled had come to believe that the government had lost control of the situation.[17]

Soon, the “crisis” came to be about the refugees themselves. Did they really deserve asylum? Were they trying to game the system? Were they merely economic migrants in disguise? Why hadn’t they applied for asylum in Greece, the country of first arrival, as required by the EU’s Dublin regulations? Most fatefully, did they pose a danger? Were the single young men who represented the bulk of migrants prone to crime? Had ISIS smuggled in terrorists?

In Germany and other European nations, no discussion can take place about migrants from the Middle East without the question of terrorism being in people’s minds. The January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris was followed by another Paris attack that November that claimed 130 lives, barely three months after Merkel’s decision. In 2016, attacks in Brussels and Nice added to the mounting insecurity. Then, in December 2016, a terrorist attack in Berlin killed 12 people. Growing anxiety about public safety and security, shamelessly exploited by anti-immigrant politicians and media, fed the emergent crisis narrative, transforming the “refugee crisis” into a “security crisis.”

Crime and sexual violence also became a widely shared concern. In Cologne on New Year’s Eve of 2015-2016, large groups of young, mostly immigrant men, intimidated and sexually assaulted hundreds of women. Many victims were robbed. Public outcry was immediate, sparking anti-immigrant demonstrations and violence. Media narratives added to the moral panic, portraying the young male immigrants as inherently violent and misogynistic products of a Middle Eastern, Islamic culture that proved integration would be impossible. Cologne became a metaphor for Merkel’s “mistake.” Anti-immigrant violence—already escalating with near-daily arson attacks on refugee housing—worsened, along with belligerent demonstrations in the east.[18] Together these events added to the growing perception of disorder. Welcome, for many, soured.

However, it was the virulently anti-refugee and far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), in radically challenging Germany’s centrist political order, which transformed the refugee crisis from something to be managed to a problem that required a definitive solution.

Founded in 2013 as a “Euro-skeptic” party, the AfD quickly made the arrival of refugees its mobilizing focus, with a simplistic keep-them-out/send-them-back narrative that found a receptive audience particularly in eastern Germany but also throughout the country.[19] In 2016, the AfD made substantial gains in several state and local elections. Then, in the 2017 federal elections, the AfD delivered a shock to the body politic, capturing 92 out of 709 seats in the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament. It was the first time since Nazi rule and the reconstruction of democracy that a far-right party had entered parliament.[20] Moreover, because the center-right and center-left parties had formed what is known as the “grand coalition,” the AfD became the largest opposition party in the federal legislative body. An unprecedented crisis of Germany’s post-war political order now gripped the country. Almost everyone I interviewed a year later expressed a palpable sense of danger about the immediate and potential consequences of the AfD’s electoral successes. No one could predict where they might end.

How this could have happened became one of the most urgent political questions in the country. For many center-right politicians, the popularity of the AfD’s anti-migrant/anti-immigrant campaign was evidence enough that the Chancellor had made a grave mistake that must be reversed.

There can be little doubt that Merkel’s “We can do this” optimism had misjudged Germany’s cultural capacity to rise to the challenge she put before them; that she had underestimated the problems that could accompany uprooted and unassimilated young men, including the fears and antagonisms that followed; and most importantly, that she had vastly misjudged the potential of the Far Right to exploit the situation for political gain.

However, the readily agreed-upon explanation that the political crisis was caused by “Merkel’s mistake” was too linear and reductionist. The declines of the center-right and center-left parties in elections following 2015 are likely to have several causes. Had other European governments agreed to a greater share of the responsibility for taking in the refugees, a goal that Merkel pursued mostly in vain, the pressure on Germany to act would have been eased. The same could be said about the tepid response of the Obama administration to the surge of refugees fleeing the Syrian civil war.[21] Further, right-wing populist parties were already on the rise or already in power in other parts of Europe, and in 2016, the election of an anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim U.S. president was hailed as a turning point for Europe. If Trump could win on a xenophobic message, so could the AfD.[22]

The Far Right’s Anti-Migrant and Anti-Islam Campaign

People rarely move to the Right for a single reason, and the emergence of populist far-right parties throughout Europe is no simple matter. Researchers emphasize the importance of resentments toward entrenched power and the remoteness of political, economic, and cultural elites.[23] In Germany, such resentments are exacerbated by feelings of second-class citizenship among Germans in the east, marked by increasing inequality, widening regional and rural-urban disparities, lack of public services, stagnation of wages, housing costs, weakening of unions, and increasing economic precarity. The financial crisis of 2008 and the austerity measures that followed only made this worse.

Germany’s Far Right skillfully exploited these resentments with political rhetoric that mobilized public antagonism against refugees and promised that only they could protect the nation from those who are said not to belong. When the AfD refocused its program on the refugee threat and began to promote a xenophobic and anti-Islam message, its electoral fortunes began to rise.[24]

Hateful and violent speech aimed at refugees and immigrants can be found across the Internet, in German media, at demonstrations and political rallies, electioneering billboards, state parliaments, and the national Bundestag. Typically, the rhetoric combines the language of invasion with familiar stereotypes of migrants as violent criminals, terrorists, and sexual predators. The AfD uses all these tropes, yet its emphasis on the threat of Islam stands out, as Islamophobia became the weapon of choice in what the party portrays as a struggle for survival of the German nation and Western civilization.

In late 2014, as the number of refugees entering Germany began to climb, a loose-knit group calling itself PEGIDA, or “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident,” organized weekly demonstrations in Dresden. On one occasion, PEGIDA mobilized 25,000 participants, including neonazis.[25] Although PEGIDA’s slogans covered a range of populist themes, its consistent focus was, as the name suggests, the threat of Islam.[26] Following the Cologne sexual assaults, the Leipzig branch of PEGIDA organized a 2,000-person demonstration in January 2016.[27] Participants held signs that read “Rapefugees Not Welcome,” alongside an image of Muslim men chasing a White woman with knives.[28] Although it still organizes some rallies, PEGIDA has now been eclipsed by the AfD. And AfD, for its part, acknowledges the group’s role in its success, with one party leader, Björn Höcke, noting, “Without [PEGIDA], the AfD would not be where it is.”[29]

It’s difficult to overstate how central anti-Muslim ideologies and politics have become in Europe. One of Europe’s most brazen anti-immigrant ideologues, far-right Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, claims to be defending his Christian “homeland”[30] from “Muslim invaders.”[31] His counterpart in Poland, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, openly declares his agenda is to “re-Christianize” Europe.[32] In France, Marine Le Pen’s powerful National Rally party portrays Muslim immigrants as a security threat and antithetical to French secularism; in 2010, she compared Muslim prayers in public spaces to the Nazi occupation.[33] In Holland, Geert Wilders, who founded the anti-Islam Party for Freedom, has been campaigning against Muslims and Islam since the 2000s, including by labeling Islam a “violent, imperialistic and fascist ideology” and referring to Muhammad as “the devil representing this ideology.”[34] He has also called the Quran “an evil book.”[35] In April 2015, Wilders spoke at a PEGIDA rally in Dresden, saying, “We have had enough of the Islamization of society.”[36] As more groups and parties promote anti-Islam themes, their influence and interconnections grow across the continent and beyond, including in the U.S.

In Germany, the AfD is now one of the most influential sources of anti-Muslim rhetoric in the public sphere. Like PEGIDA, the AfD promotes the specter of Islamization as a grave threat to the nation, both in cultural and demographic terms. The AfD’s nearly 100-page party platform claims that “Islam does not belong to Germany” and is “a danger to our state, our society, and our values.”[37]

It reads: Islam does not belong to Germany, women’s freedom cannot be traded.

One widely used AfD campaign poster features three Muslim women wearing niqabs and the words, “Stop Islamization/Vote AfD.”[38] Another portrays two White women in bikinis accompanied by the words, “Burkas? We Support Bikinis.”[39] These themes were combined in a now infamous 2019 poster, which included an image of an Orientalist painting from the 19th Century titled “Slave Market.” The painting portrays a naked, light-skinned woman surrounded and being examined by dark-skinned men in turbans. The poster reads, “So that Europe Does Not Become Eurabia/Europeans choose AfD.” The connotations are unsubtle, referring not only to sexual enslavement but also fears of Muslim sexual aggression. But beyond that, the poster also references the “replacement” narrative increasingly found throughout Europe and the United States: that unless something is done, Muslims and the culture they bring will overwhelm and replace “Europe”—people and culture alike.[40]

The “Great Replacement” theory stipulates that mass migration and demographic expansion of non-White and (in Europe) especially Muslim people will overwhelm White people or Christians.[41] The idea has been taken up by a variety of far-right groups, from Identitarians who claim they are merely defending their own culture, to those raising the specter of “White Genocide.”[42] The theory has also been employed as justification for mass violence against Muslims in Europe, New Zealand, and the U.S.[43] In 2011, a Norwegian replacement theory conspiracist claimed “demographic warfare” and the threat of liberal-left multiculturalism as justifications for the murders of eight people in Oslo and 68 more on a Labor Party youth retreat on a nearby island. In 2019, the shooter who killed 51 people in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, wrote a manifesto in which he proclaimed that immigration was “an assault on the European people,” adding, “This is ethnic replacement. This is cultural replacement. This is racial displacement. This is WHITE GENOCIDE.”[44] Also in 2019, the shooter who killed 23 and injured at least 23 more mostly Latinx people in El Paso, Texas, justified the attack by citing the Great Replacement.

The demographic/biological danger of Islamization is also portrayed in an AfD poster featuring a pregnant White German woman and the slogan, “New Germans? We’ll make them ourselves.”[45] The message is clear: If there are not enough of us and too many of them, they will replace us. The pregnant woman in the poster is doing her duty to the nation by “making” a genuine German, in clear contrast to imposters who can never be German. The AfD’s Björn Höcke has been explicit, warning in a 2018 book of “the death of the nation through population replacement,” and calling for a “remigration project” that will by necessity be carried out by force. “I am afraid that there will be no avoiding a policy of ‘well-tempered cruelty,’” he wrote. “Existence-threatening crises require extraordinary action.”[46]

Another AfD poster features joyful, White children skipping down a school hallway. The text reads, “Germany’s Leading Culture! Islam-free Schools!”[47]—a chilling resonance, in the use of the German phrasing Islamfrei, with the Nazi quest to make Germany Judenfrei—free of Jews.[**]

Since advocacy of a racial nation is forbidden in post-Nazi Germany, the AfD unsurprisingly denies its anti-Islam campaign is racist. In its 2017 “Manifesto for Germany” the party claims that immigrants must become integrated or assimilated to obtain permanent residence and warns of “counter-societies and parallel societies in our country.” But does integration translate into acceptance? Like the Conversos of 15th Century Spain—Jews who converted to Christianity under threat of death during the Spanish Inquisition—within AfD framing, Muslims in Germany will always be under suspicion and never fully belong to the sacred, bio-cultural community of the nation. In the same Manifesto the AfD declares, “Islam does not belong to Germany. Its expansion and the ever-increasing number of Muslims in the country are viewed by the AfD as a danger to our state, our society, and our values.”[48] This is an extraordinary declaration. If Islam does not belong to Germany, then the presence of Muslims is a transgression against the nation-state. Incompatibility is absolute. If history is a guide, the distance between the rhetoric of exclusion and compulsory removal is short, as the AfD’s Björn Höcke has already made clear in his advocacy of forced “remigration.”

Even more alarming, the claim of not belonging is not confined to the Far Right. Center-right politicians aiming to win back voters have adopted AfD’s anti-Islam slogan. Most prominent among them is former CSU leader Horst Seehofer, Germany’s Federal Minister of the Interior, Building and Community since 2018. Seehofer became well known for leading the challenge to Merkel’s 2015 refugee decision from within the center-right alliance, declaring that migration is “the mother of all political problems.”[49] Shortly after becoming Interior Minister, Seehofer adopted the AfD’s radical slogan, “Islam does not belong to Germany,”[50] in a bid to strengthen his credentials among AfD voters. Germans don’t have to vote for the AfD, Seehofer seems to have reasoned; they can rely on the center-right to more responsibly advance the same positions taken by the Far Right—such as the not belonging plausibly implied by policies like rejecting asylum applications, increasing deportations, and strategies to prevent migrants from reaching Germany.

Seehofer is not alone. Center-right political leaders, including then CDU/CSU parliamentary leader Volker Kauder[51] and Stanislaw Tillich, the CDU Minister-President of Saxony at the time, have proclaimed that Islam does not belong to Germany.[52] And CSU parliamentary leader Alexander Dobrindt has repeatedly echoed the phrase and further declared that Islam “has no cultural roots in Germany and with Sharia as a legal system, it has nothing in common with our Judeo-Christian heritage.”[53]

Nationalism Reinvented

The language of belonging and not belonging reveals the extent to which the AfD has attempted to transform the refugee crisis into a crisis of national identity. In 2015, the militant “Wing” faction of the AfD, in its founding document, declared itself to be a “resistance movement against the further erosion of German identity.”[54] “Foreigners out!,” the perennial slogan of xenophobes everywhere, can now be heard at far-right demonstrations.[55]

The Far Right’s conception of the national community it claims to defend promotes a cultural-ethnic nationalism that both hides and obliquely expresses racial meaning. In contemporary Germany, the AfD cannot openly proclaim the ideal of a racial nation, but that constraint does not prevent stigmatizing slanders against refugees that are clearly racist in both intent and content, even if the word “race” is avoided. Nor does it inhibit the AfD from promoting an exclusive conception of the national community that is at minimum ethnic and at the same time connotes race for those receptive to racial thinking.

First, consider the slogan Das Volk (the people), which appears frequently in AfD posters and other party statements. In current usage, Das Volk connotes German ethnicity or a sense of shared culture, language, and history. But the phrase also has deep historical meanings. Consider one AfD slogan, “Back then like today: We are The People,” used in Eastern Germany, which explicitly links past to present. In this case, it links the present to the 1989 revolution against East Germany’s Communist regime, when the phrase was a prominent chant during demonstrations.[56] However, the phrase is also known for its place in the lexicon of the Nazis, for whom it signified a racial national identity. The Nazi concept of Das Volk and Völkisch nationalism employed meanings of race that had developed over more than a century in Germany and elsewhere. As cultural historian George Mosse brilliantly observed in Toward the Final Solution, racial conceptions of national identity have always incorporated or “annexed” multiple meanings, including ideas of a mythical past; supposed metaphysical properties like Volksgeist (“the unchanging spirit of a people refined through history”); and ideas associated with class, gender, the land, and German national destiny. These absorbed meanings give racial or ethnic nationalism a cultural depth that binds the biological with the cultural.[57] In other words, ethnicity remains a salient category and the unacknowledged category of race is understood—at least by many—to be one of its defining characteristics. Moreover, in focusing on threats, Völkisch nationalism always implies both a demographic danger to bio-ethnic identity and to the culture believed to derive from that identity. “White” or “Aryan” may never be denoted when Das Volk, “German,” or “German culture” are used in an AfD campaign, but they are clearly implied. Note that only in 1999 did Germany finally abandon its reliance on descent as the principal criterion for citizenship (jus sanguinis) and adopt a definition of citizenship that thereafter included birth in the country (jus soli). Unsurprisingly, the AfD rejects the newer citizenship law and distinguishes the authentic “Bio-deutscher” from the “Pass-deutscher,” the latter referring to those who have acquired a German passport through migration.

Second, the AfD employs another theme drawn from Völkisch nationalism: the old German term Heimat. Too easily translated as “homeland,” Heimat more fully connotes feelings of belonging, attachment, and security of place, tradition, extended family, community, and the familiar. Yet as early as the late 19th Century and throughout the Nazi period, Heimat also became a term that signified racialized properties of Das Volk and was incorporated into the Nazi ideal of “blood and soil.”[58]

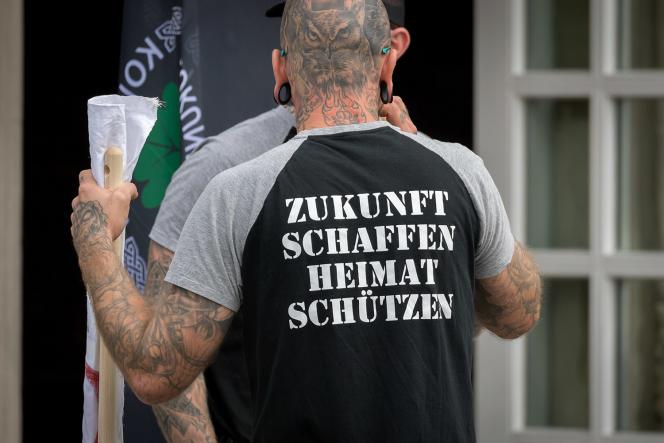

The AfD’s use of Heimat is thus a powerful signifier of the national cultural essence said to be threatened by uprooted migrants with their “foreign” ways and religion. One AfD poster reads “For a Secure Heimat, Stop Islamization,” blending security fears with the implication that German identity is also insecure. Stopping the invasion, it suggests, requires not only securing national borders but also the borders of identity.[59]

If there is any doubt of Heimat’s Völkisch meaning, consider the poster from a January 2015 PEGIDA protest in Dresden that reads, “Stop Multiculturalism—My Heimat Remains German.”[60] Here, Heimat is not only a national culture understood as “German,” but a culture that has always been and must always remain in the possession of those who claim it as their collective identity. Heimat belongs to Germans just as Islam does not. More broadly, multiculturalism is depicted as the enemy of German Heimat. The nation cannot be a shared cultural space, and the people cannot tolerate ideological enemies who promote a plural nation.[61]

Finally, German history is referenced by the AfD in other significant ways. There are longstanding resentments about the public culture of remorse and responsibility for Nazism, WWII, and the Holocaust.[62] AfD politicians denounce what they call Germany’s “shame culture.”[63] Referring to the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, AfD’s Björn Höcke said, “Germans are the only people in the world who plant a monument of shame in the heart of the capital.”[64] AfD co-founder and “honorary chairman” Alexander Gauland infamously asserted that the Nazi era was “just a speck of bird poop” on the glorious history of the German nation and its soldiers’ sacrifices on the battlefields of WWI and WWII.[65]

Moving Right to Contain the Right

In addition to the adoption of far-right rhetoric by prominent center-right politicians, a much broader consensus quickly emerged among centrist parties that the only way to win back voters who defected to the AfD was to cut off the oxygen that seemed to be feeding the far-right fire. That meant clamping down on further migration and on the refugees already in Germany who had been denied or not yet granted asylum. A human rights activist I interviewed characterized the prevailing thinking as, “Contain the flow of migrants or suffer the political consequences.” Similar advice came from Hillary Clinton in 2018: “I think it is fair to say Europe has done its part and must send a very clear message—‘We are not going to be able to continue to provide refuge and support’—because if we don’t deal with the migration issue it will continue to roil the body politic.”[66] In a 2018 Atlantic article, the neo-conservative David Frum, writing for U.S. readers, was blunter still: “If liberals won’t enforce the borders, fascists will.”[67]

The governing coalition’s reversal on migration is nothing short of astounding. As early as September 2015, Germany began closing its borders to additional refugees and reconfirming the Dublin regulations—the very regulations it had suspended in late August. Germany adopted border controls with Austria and other neighboring countries to prevent secondary or internal-EU migration of refugees.[68] In a 2018 public confrontation with Merkel, Interior Minister Horst Seehofer, the government’s most prominent immigration restrictionist, successfully pushed the government to adopt a hardline position, including expelling and temporarily incarcerating migrants who don’t qualify for asylum in so-called “transit centers.”[69] In arrangements worked out with Greece, Spain, and (more contentiously) Italy, migrants are now forcibly returned to those countries for asylum processing and residency or deportation. Most political leaders joined in supporting the tougher measures. After some opposition, then-Social Democratic Party (SPD) leader Andrea Nahles nodded her approval, stating that Germany “cannot accept all.”[70] Aiming to win back voters who had defected to the AfD, dissidents from the Left Party and SPD formed a political group known as Aufstehen or Stand Up that pushed a restrictionist line.

Most of the refugees who entered in 2015 and have not yet been approved for residency or asylum now face tightened criteria and fear deportation to their EU country of first arrival or, upon a negative decision, deportation to a “safe country of origin.”[71] Controversially, until August 2021, parts of Afghanistan had been designated as “safe” by the German government, allowing for large numbers of deportations.[72] When churches responded to deportations to Afghanistan or other destinations by providing sanctuary, they faced increased political and legal pressures from the government.[73] The German government’s principal strategy—a policy previously adopted and carried out by the EU—is to prevent migrants from reaching Europe by tactics designed to reinforce “external borders”[74]—tactics often referred to as “Fortress Europe.”[75] Since 2015, Germany has been a key player in support of an even stronger “fortress.” If migrants cannot reach Europe, there is no obligation under the Geneva Convention on Refugees to provide asylum to those who qualify and no obligation to abide by the requirement of not returning rejected asylum applicants to countries where their life or freedom would be endangered (the principle of non-refoulement).[76] Pressed by Germany, the EU implemented an agreement with Turkey in March 2016 to prevent migrants from crossing into Greece and Bulgaria.[77] Migration through Turkey was drastically reduced. The EU-Turkey deal—with its offer of money and other inducements in exchange for keeping migrants out of Europe—was modeled on an earlier deal between Italy and Libya that also included EU and Libyan sea patrols. Across the Mediterranean, EU patrols and returns carried out by Frontex, the EU’s European Border and Coast Guard Agency, have risen steeply since 2016.[78] Given the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan and another crisis of forced migration already developing, Germany and five other EU member states recently warned of a replay of 2015, worrying that “stopping returns sends the wrong signal and is likely to motivate even more Afghan citizens to leave their home for the EU.” [79]

On the frontline of exclusion, Fortress Europe strategies, especially the EU-Turkey deal and its replicas, have dramatically reduced the number of refugees able to reach Europe. In late 2019, Turkey temporarily suspended the EU deal and the number of refugees reaching Greece increased, a move that was quickly blocked by Greece’s new conservative government.[80] Even so, migrants still risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean or on the long trek across central Asia, encountering “push backs” from both national and Frontex patrols.

A struggle over the direction of the ruling parties in Germany continues. On the local level, instances of cooperation between center-right parties and the AfD are occurring with greater frequency. In February 2020, a spectacular violation of the informal rule that prohibits centrist parties’ cooperation with far-right parties occurred in the state of Thuringia when CDU politicians agreed to an electoral alliance with the AfD to remove a Left Party premier and install the leader of the small, pro-business Free Democratic Party.[81] These events, immediately condemned by Merkel[82] and resulting in the resignation of the FDP leader in Thuringia, triggered a crisis within the CDU, including the resignation of Merkel’s then-designated successor, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.[83]

There’s no evidence to support the claim that these rightward shifts have contained the rise of the Far Right. The restrictions on further migration adopted soon after 2015 failed to prevent AfD’s dramatic electoral gains in 2016[84] and 2017.[85] The AfD continued making gains in various state elections through late 2019[86] and didn’t begin to decline until Merkel’s ratings soared during the first several months of the pandemic crisis.[87]

More than one of my interviewees questioned the center’s strategic logic of coopting the far-right message on migration and Islam. Their views anticipated political scientist Tarik Abou-Chadi’s research that points to a similar conclusion: that “established parties that accommodate the positions and rhetoric of the radical right actually bring them into the mainstream.” Or as France’s Marine Le Pen put it, voters “always prefer the original to the copy.”[88]

The Green Party Challenge to the AfD

Compared to other center parties, the Greens have taken a more confrontational stance against the Far Right. In stark contrast to the CSU and the conservative faction of the CDU, the Greens have campaigned against the AfD’s anti-migrant, anti-Muslim vision of a purified German nation. “People are tired of the hate and the fear mongering,” said the Greens’ Bavarian co-leader Katherina Schulze.[89] A prominent party slogan reads, “Give courage instead of spreading fear.”[90] By challenging the AfD directly, the party aims to become an “alternative to the Alternative.”[91]

A prominent Green strategy is to oppose the AfD on its own symbolic turf: recognizing that the question of “who belongs” carries enormous significance in the era of mass migration, and that the AfD’s success at the polls is largely thanks to their providing a compelling answer. But the Greens are betting that many Germans are uneasy or outright opposed to the AfD’s version of nationalism and will be moved by a message of “positive patriotism”[92] with which they can identify. As Green Party co-leader Robert Habeck put it, “We see ourselves at the center of the nation, and that also means reclaiming the symbols of our country from the nationalists.”[93]

The “positive patriotism” theme is controversial, especially given that the strategy includes an effort to reclaim the politically loaded word Heimat.[94] “Politics must formulate an idea,” as Habeck put it, “an idea of Heimat, an idea of identity.”[95] In Green poster campaigns, Heimat is used to depict Germany as an open and diverse society—with people of varying cultural and ethnic backgrounds interacting joyfully together, or with Black and White hands clasped together below the slogan, “Heimat? Naturally. Vote Green against Racism.” The poster also connected the idea of Heimat to the Greens’ other policy platforms: “We struggle for better living conditions. Everyone wants to feel at home. And everyone has the right to a home.”[96]

Translation: Create the future, protect the home

Critics of the Green’s “positive patriotism” strategy, however, worry that the move risks lending credibility to nationalist sentiments no matter how they are reframed, and that the Far Right will out-maneuver its adversaries in struggles over the meaning of the nation or national belonging.

The Greens’ youth division, Grüne Jugend, tweeted “#Heimat is an exclusionary term. Therefore, it is not useful for fighting right-wing ideology. Solidarity instead of Heimat.”[97] Critics also point out that the government itself jumped on the Heimat bandwagon when it added “Heimat” to the name of the Ministry of Interior in 2018,[98] arguably as another demonstration of the center adopting a theme from the AfD. As far-right nationalist movements continue to grow, debates about whether they can be effectively countered on the symbolic turf of nationalism will multiply.[99] Yet in today’s Germany, although there is widespread uneasiness with the place of Islam in German society, the very legitimacy of the post-Nazi state depends on rejecting a definition of national belonging that is restricted to just one ethnicity or religion. The Green “progressive patriotism” strategy resonates with values supportive of diversity and attempts to mobilize national affection and pride in service of defending the constitutional order founded on democratic governance and protection of human dignity and rights. The strategy might therefore be seen as another manifestation of “working off the past” of racist nationalism and tapping into German fears of backsliding toward the Far Right.[100]

Civil Society and Grassroots Mobilizations

Over the past five years, acts of solidarity with migrants and grassroots organizing against the Far Right merged in German society and politics. From the initial outpouring of help as refugees streamed into Germany to the sustained advocacy and support provided by NGOs such as Pro Asyl (Germany’s largest pro-immigrant advocacy organization), religious congregations, neighborhood groups, and city administrations, Germans have responded to the refugee crisis with moral purpose and political activism. By one estimate, over nine million Germans have volunteered to help.[101]

At the same time, far-right anti-migrant protests and violence, and the electoral triumphs of the AfD, prompted hundreds of thousands of Germans to demonstrate against what many feared was a return of fascism. In October 2018, over 240,000 people took to the streets of Berlin for a protest march organized by a new grassroots group called Unteilbar (“Indivisible”).[102] A few weeks earlier there were similar protests in Hamburg.[103] Both demonstrations followed violent protests in Chemnitz in late August 2018, one of them 8,000-strong and led by identifiable neonazis.[104] In late August 2019, Unteilbar organized another demonstration in Dresden,[105] just before the elections in Saxony and Brandenburg, which drew an estimated 40,000 people.[106] More demonstrations followed the September elections,[107] as well as protests against the neonazi National Democratic Party (NPD), and again after the February 2020 far-right terrorist attack in Hanau on people with migrant backgrounds.[108] Also in early 2020, cooperation between the CDU and the AfD in a Thuringia state election[109] ignited street protests under the banner, “Not with us! No pacts with fascists anytime or anywhere!,”[110] and precipitated a shakeup at the highest level of the CDU.[111]

Anti-racist social media campaigns and other educational initiatives also proliferated, some supported by federal and local governments. One of the most prominent civil society organizations undertaking this work is the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, which hosts Belltower News, a website that monitors far-right developments. Legal aid and human rights organizations, as well as unions, political parties, religious groups, and progressive activists of various stripes all joined organizing against racism and the Far Right and in support of immigrant rights.[112] Support for migrants quickly became a matter of defending them in the political sphere, including advocacy for housing and other services and protection from deportation or far-right violence.[113]

Translation: No cooperation with AfD

Despite significant challenges, the solidarity movement remains strong. Demonstrations[114] involving thousands protested a proposed law[115] that would expand deportation and criminalize some pro-migrant activism. Other demonstrations protested deportation flights to supposedly safe countries of origin such as Afghanistan.[116] Solidarity groups from Germany joined a growing pan-European movement, aligning with groups like Seebrücke (“Sea Bridge”) to protest deaths in the Mediterranean[117]—an estimated 11,451 between 2014 and the end of 2020, with an additional 955 deaths in the first half of 2021[118]—and the criminalization of civil society rescue efforts. Periodic demonstrations[119] against the “living hell”[120] of the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos have been followed by additional protests after[121] the September 2020 fire that destroyed the camp.[122] Activist groups press the government to take in more refugees, especially those displaced by the fire. They have been joined by 170 German towns and cities that have indicated their willingness to take in refugees.[123] However, the situation for migrants who arrived in 2015 and 2016 and remain in Germany today is complex. While up to 250,000[124] have not been granted asylum and are therefore living under threat of deportation, the majority have begun to make a life in Germany, with considerable assistance from government agencies, civic groups, and ordinary Germans who continue to offer help.[125]

Developments During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The AfD has not fared well during the pandemic, with its approval ratings twice dropping below 10 percent (although this August, shortly before the September general election, it rebounded to 11 percent).[126] Most voters worried more about the virus than Muslim refugees, and Merkel’s bold public health measures won their approval.[127] Further, the AfD has become preoccupied with an internal struggle involving its militant “Wing” faction, which was formally dissolved after the Office for the Protection of the Constitution designated it a “proven extremist endeavor.” In reality, the Wing is still functioning and powerful.[128] The party has also been damaged by several incidences of far-right violence in the last two years that have attracted significant public attention. The first was the June 2019 assassination of Walter Lübcke, a prominent CDU official and vocal immigrants’ rights advocate, whose death marked the first far-right murder of a politician since WWII.[129] Then, in October 2019, on Yom Kippur, a far-right gunman intent on mass murder attacked a synagogue in Halle. The assailant was thwarted from entering the synagogue but shot and killed two people outside.[130] In February 2020, an assassin killed nine people with migrant backgrounds in Hanau.[131] After this attack, Germany’s Justice Minister declared that “far right terror is the biggest threat to our democracy right now.”[132] Recently, the domestic intelligence agency announced its intention to label the AfD as an “extremist” organization to be put under surveillance,[133] although a court has temporarily blocked the move.[134]

Desperate for a mobilizing issue, some AfD affiliates joined with other groups in May 2020 to protest against the first COVID lockdown and other government public health measures.[135] They did so again that August, when an estimated 20,000 marched in Berlin for “freedom” from government restrictions.[136] In late August 2020, an even larger demonstration, estimated at 38,000, protested Merkel’s COVID policies, their economic consequences, and the fear of future compulsory vaccination, followed by an alarming attempt to storm the Reichstag by a few hundred far-right protesters.[137] With the second-wave lockdown in winter, the AfD increased its efforts to capitalize on mounting economic hardships and pandemic exhaustion and to align itself with the demand for reopening the economy.[138] Yet there is no indication that the party has benefitted from this shift.

Whether the AfD will avoid significant losses in the September 2021 elections is unclear. In several recent state elections, the party has lost about a dozen seats.[139] But even if the party loses some representation in the Bundestag, it will remain a force with the ability to promote its nationalist and anti-Muslim/anti-migrant agenda. While new migration has been radically reduced,[140] the “asylum seeker protection rate” from 2015 to 2021 has been as high as 62.4 percent (2016) and as low as 34.4 percent (2021).[141] In a period of persistent high unemployment,[142] the AfD continues to target migrants for taking jobs that “belong to Germans” and for relying on public benefits. The appeal of this rhetoric for many Germans means that the AfD will likely be a serious contender in the electoral arena for the foreseeable future.

Other far-right groups promoting anti-migrant and anti-Muslim views remain active. PEGIDA, Identitarians, Reich Citizens, militant anti-lockdown and anti-vaccine groups, QAnon, and an unknown number of underground neonazi and other hate groups inclined to violence are active throughout Germany.[143] Threats and attacks on migrants, Jews, and migrant-supporting politicians continue to occur.[144] In the summer of 2020, a network of far-right members of the military, police, and veterans was identified as having plans to murder political enemies.[145] This spring, a closely-watched trial began for an active-duty soldier accused of plotting with a network of far-right actors to assassinate German political leaders and activists and bring on a collapse of the state in a revolt they named “Day X.”[146] The soldier’s 2017 arrest and revelations of his alleged plot have alarmed both German security agencies and the public to the extent of far-right infiltration of the military and other security units. Growing concern about far-right violence may contribute to AFD losses in the upcoming September election.

Beyond 2021, the success of Germany’s Far Right will depend on several developments related to migrants and migration. Fortress Europe may once again be breached by a new wave of mass displacement, such as the recent Taliban seizure of power in Afghanistan, or by Turkey pushing refugees toward Greece. Islamist terrorist attacks may fade or escalate. A severe economic downturn could easily reinforce nativist sentiments. Electoral victories by far-right and anti-Muslim parties in countries like France and Italy would likely contribute to a European political climate favorable to all far-right parties. Not least, the political direction of the United States and how border issues are handled will prove critical.

Beyond Germany: Migration and the Far Right

Four years of Trump’s violent and hateful speech and nativist policies, enthusiastically embraced by his White nationalist base, along with a sharp rise of violent bias crimes, and then the January 6 insurrection, have spawned a recognition that Americans face a grave threat from the Far Right. With Trump and his loyalists still in control of the Republican Party, danger signals continue to flash red. As in the past, migrants crossing the border will provide Republicans and right-wing media opportunities for a racialized politics of resentment and fear.

Anti-migrant politics in the U.S. display many of the same elements as can be found in Germany: the same reliance on images of “invasion,” similar stereotypes about migrants’ supposed innate and unassimilable traits and cultures, identical claims of threat to an existing culture said to be in danger of being “replaced.” The narrative of replacement in Germany, and Europe more broadly, focuses on Islam. In the U.S., anti-Muslim or anti-Islam politics are also widespread but often overshadowed by the perceived threat of a porous southern border. That might not last. Trump started off his presidency with his infamous “Muslim travel ban”[147] and continued to make anti-Muslim comments throughout his time in office.[148] Prominent Republican politicians have done the same,[149] and since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, well-financed anti-Muslim movements, like Act for America, have become more influential.[150] But replacement ideology is malleable: sometimes applied to Muslims (as in anti-Sharia campaigns), and other times to Latinx immigrants (as evidenced in the 2019 El Paso massacre); on some occasions to Jews (as in Charlottesville in 2017 or the 2019 shooting in a synagogue near San Diego), and to Black people any time, any place. White anxiety about being replaced was also recently found to be a major factor motivating the January 6 insurrectionists.[151]

How Democrats, the national media, and civil society respond are open questions. While Biden’s initial immigration initiatives are encouraging, a continuing flow of migrants seeking asylum will test his commitment in the context of Republican fear-mongering and public anxieties. When Kamala Harris travelled to Guatemala in early June, her “Do Not Come”[152] message signaled an administration already on the defensive about another border “crisis.” The continuing reliance on Title 42, which empowers border enforcement agencies to turn away migrants for public health purposes,[153] keeps the border closed to migrants who then seek to cross in more remote and dangerous areas. What should be clear is that migration has moved to the center of political conflict. The UN refugee agency estimates that the current population of forcefully displaced people now numbers over 80 million people.[154] Like Germans, Americans will have to grapple with their moral and political obligations toward people seeking refuge and a more secure life.

Consider the following questions: How will understandings of the nation and national community accommodate or fail to accommodate a world where forced migration continues to press nations in the Global North to respond? How many displaced people can Germany or the U.S. reasonably accept? What moral price are Germans or Americans willing to pay for exclusions and the inevitably coercive and often violent means employed to enforce them? Are the world’s powerful nations willing to confront how their foreign policies destabilize countries of origin and how their wars contribute to the human flow? Are they capable of reordering their systems of production and consumption in ways that do not contribute to worsening global inequality?

“Refugee crises,” or better said, humanitarian crises, will reappear. War and persecution-related displacements will not cease. Climate catastrophes will inevitably deepen the crisis for people living in poorer regions and drive them to seek safety in countries with resources for a sustainable life. The extraordinary number of deaths along migration routes,[155] along with inhumane conditions in the refugee camps and detention centers, will continue to trouble the conscience of Germans and Americans—at least among those who care to look. The temptation will be not to look, aided by strategies of remote control that rely on other countries to prevent migrants from reaching the German or U.S. border.

Germany, the United States and other destination countries will have to choose. Either meet the moral and political challenge with its enormous difficulties or give their countries over to anti-migrant nationalist closure. In opting for a version of the latter, center politicians might fall back on proclamations like “if liberals won’t control the borders, fascists will.”[156] By hoping to fend off the Far Right by moving Right themselves, they risk, as one observer put it, “becoming the beast they are fighting against.”[157]

The twin crises of forced migration and anti-migrant, far-right, nationalist movements are defining events of our times. How they are understood and responded to will determine Germany’s and America’s political, cultural, and moral futures, and those of destination countries everywhere. Not least, the fates of the world’s forcibly displaced people are at stake.

Endnotes

- Nikkie McCann Ramirez, “Tucker Carlson, the face of Fox News, just gave his full endorsement to the white nationalist conspiracy theory that has motivated mass shootings,” Media Matters, April 9, 2021, https://www.mediamatters.org/tucker-carlson/tucker-carlson-face-fox-news-just-gave-his-full-endorsement-white-nationalist.

- "Forced Migration or Displacement," International Organization for Migration (IOM), Migration Data Portal, Last Updated June 30, 2021, https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/forced-migration-or-displacement#:~:text=According%20to%20UNHCR%2C%20the%20number,million%20forcibly%20displaced%20people%20as.

- Susan Neiman, Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2019).

- Francis Markus, “Asylum claims from Syria, Iraq and other conflict zones rise in first half 2014,” UNHCR, September 26, 2014 https://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2014/9/54242ade6/asylum-claims-syria-iraq-other-conflict-zones-rise-first-half-2014.html.

- Phillip Conner, "Most Displaced Syrians are in the Middle East and about a Million are in Europe," Pew Research Center, January 29, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/29/where-displaced-syrians-have-resettled/.

- “Mediatization and Politicization of Refugee Crisis in Europe,” Special Issue, Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 16, 1-2 (2018).

- Amanda Taub, “Germany just did Something Huge for Syrian Refugees—and the Future of Europe,” Vox, August 28, 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/8/28/9220395/germany-migrant-crisis.

- "Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015," Eurostat News Release, March 4, 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6.

- Kate Brady, “German interior minister revises 2015 refugee influx from 1.1 million to 890,000,” Deutsche Welle, September 30, 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/german-interior-minister-revises-2015-refugee-influx-from-11-million-to-890000/a-35932746.

- Anthony Faiola and Stephanie Kirchner, “Merkel Condemns Rash of Neo-nazi attacks in Germany,” Washington Post, August 25, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/merkel-condemns-rash-of-neo-nazi-attacks/2015/08/26/8b485a28-bf16-4391-8214-597ec626d815_story.html; Sophie Hinger, Priska Daphi and Verena Stern, “Divided Reactions: Pro- and Anti-Migrant Mobilization in Germany,” Ch. II in The Refugee Reception Crisis in Europe, Ed. Andrea Rea, Marco Martiniello, Bart Meuleman (Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2019), https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/24581.

- “Germany Spent 20 Billion Euros on Refugees in 2016,” Deutsche Welle, May 24, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-spent-20-billion-euros-on-refugees-in-2016/a-38963299.

- Neiman, Learning from the Germans.

- “No German Identity without Auschwitz,” The Local, January 27, 2015, https://www.thelocal.de/20150127/no-german-identity-without-auschwitz-gauck.

- Perla Treviso,” German Volunteers Surmounts Refugee Backlash,” Coda, December 30, 2016, https://www.codastory.com/migration-crisis/integration-issues/volunteers/

- Bart Bonikowski and Daniel Ziblatt, "Mainstream conservative parties paved the way for far-right nationalism," The Washington Post, December 2, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/12/02/mainstream-conservative-parties-paved-way-far-right-nationalism/.

- “Turkish Guest Workers Transformed German Society,” Deutsche Welle, October 30, 2011, https://www.dw.com/en/turkish-guest-workers-transformed-german-society/a-15489210; Stephen Szabo, “Germany and Turkey: The Unavoidable Partnership,” Brookings, March, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/germany-and-turkey-the-unavoidable-partnership/.

- Damien Sharkov, “Over 80 Percent of German Think Merkel Has Lost Control of Refugee Crisis,” Newsweek, February 4, 2016, https://www.newsweek.com/80-percent-germans-think-merkel-lost-control-refugee-crisis-422945.

- “Flames of Hate Haunt a Nation,” Spiegel International, July 24, 2015, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-registers-sharp-increase-in-attacks-on-asylumseekers-a-1045207.html; “Germany hate crime: Nearly 10 attacks a day on migrants in 2016,” BBC, February26, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39096833.

- Frank Decker, “The ‘Alternative for Germany’: Factors Behind its Emergence and Profile of a New Right-wing Populist Party,” German Politics & Society 34, no.2 (January 2016): 1-16.

- Holly Ellyatt, “‘I am afraid’: First far-right party set to enter German parliament in over half a century,” CNBC, September 22, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/22/first-far-right-party-to-enter-germanys-parliament-in-over-half-a-century.html.

- Michael Ignatieff, “The Refugees and the New War,” The New York Review of Books, December 17, 2015, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2015/12/17/refugees-and-new-war/.

- Ed Pertwee, “Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43, no. 16 (April 2020): 211-230, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688.

- Federico Finchelstein, From Fascism to Populism in History, chapter 2 (Oakland, Ca: University of California Press, 2017).

- Shadi Hamid, “The Role of Islam in European Populism: How refugee flows and fear of Muslims drive right-wing support,” Foreign Policy, February 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/FP_20190226_islam_far_right_hamid.pdf; Liz Fekete, Europe’s Fault Lines: Racism and the of the Right (London: Verso, 2018).

- Malte Thran and Lukas Boehnke, “The Value-Based Nationalism of Pegida,” Journal For Deradicalization, No. 3 (Summer 2015), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301681559._

- Helga Druxes and Patricia Simpson, “Introduction: Pegida as a European Far-Right Populist Movement,” German Politics and Society, 34, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 1-16; David Coury, “A Clash of Civilizations? Pegida and the Rise of Cultural Nationalism,” German Politics and Society 34, no.4 (Winter 2016): 54-67.

- Naomi Conrad, “Leipzig, a city divided by anti-Islamist group PEGIDA,” Deutsche Welle, January 11, 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/leipzig-a-city-divided-by-anti-islamist-group-pegida/a-18972630.

- Carlo Angerer, “Cologne Sex Attacks 'Good for Us,' Anti-Refugee Protesters Say,” NBC News, January 17, 2016, https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/europes-border-crisis/cologne-sex-attacks-good-us-anti-refugee-protesters-say-n497376.

- Anti-Islam Pegida rally meets resistance in Dresden,” Deutsche Welle, February 17, 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/anti-islam-pegida-rally-meets-resistance-in-dresden/a-52411846.

- “Hungary, Poland to defend their Christian homeland, Orban says,” Reuters, April 6, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-election-poland/hungary-poland-to-defend-their-christian-homeland-orban-says-idUSKCN1HD1AV.

- Emily Schultheis, “Viktor Orbán: Hungary doesn’t want ‘Muslim invaders,’” Politico, January 8 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/viktor-orban-hungary-doesnt-want-muslim-invaders/.

- Michael Broniatowski, “Incoming Polish PM: We won’t bow to ‘nasty threats,’” Politico, December 9 2017, https://www.politico.eu/article/mateusz-morawieck-incoming-polish-pm-we-wont-bow-to-nasty-threats/.

- Kim Willsher, “Marine Le Pen faces court on charge of inciting racial hatred,” The Guardian, September 22, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/22/marine-le-pen-faces-court-on-charge-of-inciting-racial-hatred.

- Cnaan Liphsich, “Far-right Dutch Politician Brings His anti-Islam Rhetoric Back to Jerusalem,” Haaretz, January 11, 2008, https://www.haaretz.com/1.4978434.

- Freke Vuijst, “How Geert Wilders Became America’s Favorite Islamophobe,” Foreign Policy, March 1, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/01/how-geert-wilders-became-americas-favorite-islamophobe/.

- “Wilders’ Pegida Speech is Turnout Flop,” The Local, April 14 2015, https://www.thelocal.de/20150414/dutch-mp-wilders-rallies-pegida-protesters.

- Alternative für Deutschland, “Manifest for Germany: The Political Programme of the Alternative for Germany,” April 2017, p.48, https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2017/04/2017-04-12_afd-grundsatzprogramm-englisch_web.pdf.

- “Germany's AfD: How right-wing is nationalist Alternative for Germany?,” BBC, February 11, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37274201.

- Sarah Wildman, “The German Far Right is Running Islamophobic Ads Starring Women in Bikinis,” Vox, August 31, 2017, https://www.vox.com/world/2017/8/31/16234008/germany-afd-ad-campaign-far-right.

- Andrew Brown, “The Myth of Eurabia: How a Far-right Conspiracy Theory went Mainstream,” The Guardian, August 16, 2019, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/16/the-myth-of-eurabia-how-a-far-right-conspiracy-theory-went-mainstream.

- José Zúquete, The Identitarians: The movement against globalism and Islam in Europe (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018).

- Ben Lorber, “Taking Aim at Multiracial Democracy,” Political Research Associates, October 22, 2019, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2019/10/22/taking-aim-multiracial-democracy.

- Aristotle Kallis, “The Radical Right and Islamophobia,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Ed. Jens Rydgren (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018): 42-60.

- Jane Coaston, “The New Zealand Manifesto Shows How White Nationalist Rhetoric Spreads,” Vox, March 18, 2019, https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/3/15/18267163/new-zealand-shooting-christchurch-white-nationalism-racism-language.

- Sarah Wildman, “The German Far Right is Running Islamophobic Ads Starring Women in Bikinis,” Vox, August 31, 2017, https://www.vox.com/world/2017/8/31/16234008/germany-afd-ad-campaign-far-right.

- Hajo Funke, “Höche wants Civil War,” Zeit Online, October 24, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2019-10/rechtsextremismus-bjoern-hoecke-afd-fluegel-rechte-gewalt-faschismus. Translation by the author.

- Nick Robins-Early, “Germany’s New Far-Right Campaign Poster is Unsubtly Racist,” Huffington Post, September10, 2018, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/afd-poster-islam-free-schools_n_5b96a0f7e4b0cf7b00425ab7. Translation by the author.

- Alternative für Deutschland, “Manifest for Germany: The Political Programme of the Alternative for Germany,” April 2017, p.48, p.62, https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2017/04/2017-04-12_afd-grundsatzprogramm-englisch_web.pdf.

- Nicole Goebel, “Migration ‘Mother of All Political Problems, Says Interior Minister Horst Seehofer,” Deutsche Welle, September 6, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/migration-mother-of-all-political-problems-says-german-interior-minister-horst-seehofer/a-45378092.

- Rebecca Staudenmaier, “German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer: ‘Islam doesn’t belong to Germany,’” Deutsche Welle, March 16, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/german-interior-minister-horst-seehofer-islam-doesn’t-belong-to-germany/a-42999726. Notably, Merkel immediately responded to Seehofer by declaring “Islam belongs to Germany: “Merkel Contradicts Interior Minister, saying ‘Islam belongs to Germany,’” The Local, March 16, 2018, https://www.thelocal.de/20180316/islam-doesnt-belong-to-germany-says-interior-minister-horst-seehofer.

- “Merkel Ally says Islam not part of Germany,” Reuters, April 19, 2012, https://ca.reuters.com/article/uk-germany-islam-idUKBRE83I0D820120419.

- Karsten Kammholz and Claus Malzahn, “Stanislaw Tillich, ‘Islam Does Not Belong to Saxony,” Welt, January 25, 2015, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article136740584/Der-Islam-gehoert-nicht-zu-Sachsen.html.

- “‘Islam shouldn’t culturally shape Germany’-Alexander Dobrindt Claims,” Deutsche Welle, April 11, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/islam-shouldnt-culturally-shape-germany-alexander-dobrindt-claims/a-43335131.

- “AfD-The Difference between ‘Wing’ and the Rest of the Party,” Deutschlandfunk, October 29, 2018, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/afd-der-unterschied-zwischen-fluegel-und-restlicher-partei.1773.de.html?dram:article_id=462076. Translation by the author.

- “Ausländer raus,” Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, https://www.politische-bildung-brandenburg.de/themen/die-extreme-rechte/ideologie/argumente-und-parolen/auslaender-raus, Accessed August 16, 2021.

- “Against the Abuse of the Peaceful Revolution,” Deutschlandfunk Kulter, August 20, 2019, https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/erklaerung-von-ddr-buergerrechtlern-gegen-den-missbrauch.1013.de.html?dram:article_id=456846.

- George Mosse, Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978, 2020), p.xxvi and p.36.

- Emily Schultheis, “Heimat: Home, Identity and Belonging,” Institute of Current World Affairs, June 5, 2020, https://www.icwa.org/heimat-home-identity-and-belonging/.

- “Alternative for Germany Demonstration,” Getty Images, April 9, 2018, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/april-2018-germany-rostock-protestors-carry-a-banner-news-photo/976688068. Translation by the author.

- Marcel Fürstenau, “No Panacea for Pegida,” Deutsche Welle, January 26, 2015, https://www.dw.com/de/kein-patentrezept-gegen-pegida/a-18214772. English translation provided.

- Timothy Wright, “Visions of the Homeland: The AfD, Bavarian Identity, and the German Heimat Debate,” Medium, October 14, 2018, https://medium.com/@timw1814/visions-of-the-homeland-the-afd-bavarian-identity-and-the-german-heimat-debate-7bb9450769dc.

- Maja Zehfuss, Wounds of Memory: The Politics of War in Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Vincenzo Caporale, “The rise of German extremism: How shame culture catalyzes right wing extremism in Germany,” Foreign Policy News, April 13, 2021, https://foreignpolicynews.org/2021/04/13/the-rise-of-german-extremism-how-shame-culture-catalyzes-right-wing-extremism-in-germany/.

- Madeline Chambers, “German AfD Rightist Triggers Fury with Holocaust Memorial Comments,” Reuters, January 18, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-afd/german-afd-rightist-triggers-fury-with-holocaust-memorial-comments-idUSKBN1521H3.

- “AfD's Gauland plays down Nazi era as a 'bird shit' in German history,” Deutsche Welle, June 2, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/afds-gauland-plays-down-nazi-era-as-a-bird-shit-in-german-history/a-44055213.

- Patrick Wintour, “Hillary Clinton: Europe must curb Immigration to stop Rightwing Populists,” The Guardian, November 22, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/22/hillary-clinton-europe-must-curb-immigration-stop-populists-trump-brexit.

- David Frum, “If Liberals won’t enforce the Borders, Fascists Will,” The Atlantic, April 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/04/david-frum-how-much-immigration-is-too-much/583252/.

- Luke Harding, “Refugee crisis: Germany reinstates controls at Austrian border,” The Guardian, September 13, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/13/germany-to-close-borders-exit-schengen-emergency-measures.

- “Chancellor Angela Merkel and Horst Seehofer agree on a migration compromise,” Deutsche Welle, July 2, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/chancellor-angela-merkel-and-horst-seehofer-agree-on-a-migration-compromise/a-44485481; Philip Oltermann, “Germany to Roll Out Mass Holding Centres for Asylum Seekers,” The Guardian, May 21, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/may/21/germany-to-roll-out-mass-holding-centres-for-asylum-seekers.

- Cas Mudde, “Why copying the populist right isn’t going to save the left,” The Guardian, May 14, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/may/14/why-copying-the-populist-right-isnt-going-to-save-the-left.

- “Safe Countries of Origin,” Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2021, https://www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/Sonderverfahren/SichereHerkunftsstaaten/sichereherkunftsstaaten-node.html. Translation provided.

- Loveday Morris and Denise Hruby, “Europe’s contentious deportations of Afghans grind to a halt as Taliban surges,” August 14, 2021, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/afghanistan-asylym-europe-taliban/2021/08/13/c7118ae4-fabb-11eb-911c-524bc8b68f17_story.html.

- Alice Su, “As German Police Attempt to Deport Refugees, Hundreds of Churches are Trying to Shelter Them,” Washington Post, September 6, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/in-germany-churches-offer-unofficial-asylum-for-muslim-refugees/2017/09/05/1c068b68-88e6-11e7-96a7-d178cf3524eb_story.html?utm_term=.e279a103fd4f; Christoph Strack, “German Church Officials Face Charges for Helping Refugees,” Deutsche Welle, June 6, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/german-church-officials-face-charges-for-helping-refugees/a-57783108.

- “External EU Border,” European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/glossary_search/external-eu-border_en.

- “The Human Cost of Fortress Europe,” Amnesty International, July 9, 2014, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/EUR05/001/2014/en/.

- Rhona Smith, “A guide to the Geneva Convention for beginners, dummies, and newly elected world leaders,” The Conversation, January 30, 2017, https://theconversation.com/a-guide-to-the-geneva-convention-for-beginners-dummies-and-newly-elected-world-leaders-72155; David FitzGerald, Refuge Beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 5-6.

- Jennifer Rankin, “Turkey and EU agree outline of ‘one in, one out’ deal over Syria refugee crisis,” The Guardian, March 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/08/european-leaders-agree-outlines-of-refugee-deal-with-turkey.

- David FitzGerald, Refuge Beyond Reach, 2019, 197-201.

- Sabine Siebold and John Chalmers, “Six EU countries warn against open door for Afghan asylum seekers,” Reuters, August 10, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/six-countries-urge-eu-not-stop-deportations-afghanistan-belgium-says-2021-08-10/; Loveday Morris and Denise Hruby, “Europe’s contentious deportations of Afghans grind to a halt as Taliban surges,” The Washington Post, August 14, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/afghanistan-asylym-europe-taliban/2021/08/13/c7118ae4-fabb-11eb-911c-524bc8b68f17_story.html; Loveday Morris and Reis Thebault, “As Afghanistan collapse triggers desperate scenes, European officials vow to avoid another 2015, The Washington Post, August 16, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe-policy-aghan-refugees/2021/08/16/75b735a8-fe8b-11eb-87e0-7e07bd9ce270_story.html.

- “Explained: The situation at Greece’s borders,” Amnesty International, March 05, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/03/greece-turkey-refugees-explainer/.

- Holly Ellyatt, “Germany’s far-right AfD becomes kingmaker in regional election, promoting shockwaves in Berlin,” CNBC, February 06, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/06/shockwaves-in-berlin-as-far-right-afd-lends-support-to-mainstream.html.

- Joshua Posaner, “Merkel blasts ‘unforgivable’ Thuringia election,” Politico, February 06, 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-blasts-unforgivable-thuringia-election-far-right-afd/.

- Sam Denney and Constanze Stelzenmüller, “The Turingia Debacle resets the Merkel Succession—and prove the AfD is a Force to be reckoned with,” Brookings, February 28, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/02/28/the-thuringia-debacle-resets-the-merkel-succession-and-proves-the-afd-is-a-force-to-be-reckoned-with/.

- Alberto Nardelli, “German elections: AfD’s remarkable gains don’t tell the whole story,” The Guardian, March 14, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/datablog/2016/mar/14/german-election-afd-gain-remarkable-cdu-angela-merkel.

- Seán Clarke, “German elections 2017: full results,” The Guardian, September 25, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2017/sep/24/german-elections-2017-latest-results-live-merkel-bundestag-afd.

- Sheena McKenzie, “Germany’s far-right makes big gains in state elections,” CNN, September 02, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/02/europe/saxony-brandenburg-germany-state-election-results-grm-intl/index.html.

- Joseph Nasr, “Divided far-right AfD loses ground in east German stronghold,” Reuters, June 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/divided-far-right-afd-loses-ground-east-german-stronghold-2021-06-07/.

- Tarik Abou-Chadi, “Opinion: Why Germany-and Europe-can’t afford to accommodate the Radical Right,” The Washington Post, September 4, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/09/04/why-germany-europe-cant-afford-accommodate-radical-right/.

- Katrin Bennhold, “Migration and the Far Right Changed Europe. A German Vote Will Show How Much,” The New York Times, October 12, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/12/world/europe/germany-bavaria-election.html.

- Emma Snaith, “Merkel faces poll disaster as coalition support collapses and Greens surge ahead in German local elections,” Independent, October 12, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/germany-local-elections-latest-polling-angela-merkel-bavaria-vote-green-afd-a8581276.html.

- Katrin Bennhold, “Greens Thrive in Germany as the ‘Alternative’ to Far-Right Populism,” The New York Times, November 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/world/europe/germany-greens-merkel-election.html.

- Katrin Bennhold, “Greens Thrive in Germany as the ‘Alternative’ to Far-Right Populism,” The New York Times, November 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/world/europe/germany-greens-merkel-election.html.

- Katrin Bennhold, “Greens Thrive in Germany as the ‘Alternative’ to Far-Right Populism,” The New York Times, November 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/world/europe/germany-greens-merkel-election.html.

- Marc Saxer, “In Search of a Progressive Patriotism,” Medium, April 15, 2017, https://medium.com/@marc_saxer/in-search-of-a-progressive-patriotism-9fe0ebaac8e4.

- Christoph Hasselbach, “‘Heimat’ finds a Homecoming in German Politics,” Deutsche Welle, October 7, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/heimat-finds-a-homecoming-in-german-politics/a-40858357.

- Die Grünen Hessen, Twitter post, August 13, 2018, https://twitter.com/gruenehessen/status/1028936545024262144. Translation by the author.

- Grüne Jugend (@gruene_jugend), Twitter post, October 2, 2017, https://twitter.com/gruene_jugend/status/914802730367111171.

- Karen Attiah, “Opinion: Germany’s ‘homeland’ propaganda is making an inglorious return,” The Washington Post, February 10, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/02/10/germanys-homeland-propaganda-is-making-an-inglorious-return/.

- Marc Saxer, “Progressive Patriotism”; Marc Saxer, “Left Home. How the Progressives should occupy the Term Home for Themselves,” International Politics and Society, 2018, https://www.academia.edu/38075478/Linke_Heimat_Wie_die_Progressiven_den_Begriff_Heimat_f%C3%BCr_sich_besetzen_sollten; Ben Knight, “A Deeper Look at Germany’s new Interior and Heimat Ministry,” Deutsche Welle, February 12, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/a-deeper-look-at-germanys-new-interior-and-heimat-ministry/a-42554122; “Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum” (“Your Homeland is our Nightmare”), Transit 12, no. 2 (2020), https://transit.berkeley.edu/volume-12-2/. Translation by Transit editors.

- Neiman, Learning from the Germans.

- Timo Tonassi and Astrid Ziebarth, “Three Years into the Refugee Displacement Crisis: Where Does Germany Stand,” The German Marshall Fund, Policy Paper No. 36, 2018, p.13.

- Colin Dwyer, “Protesters Throng Berlin In Massive Rally To Support ‘Open And Free Society,’” NPR, October 13, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/10/13/657186450/protesters-throng-berlin-in-massive-rally-to-support-open-and-free-society.

- “Thousands protest in Hamburg against right-wing demonstration,” Deutsche Welle, September 06, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/thousands-protest-in-hamburg-against-right-wing-demonstration/a-45379946.