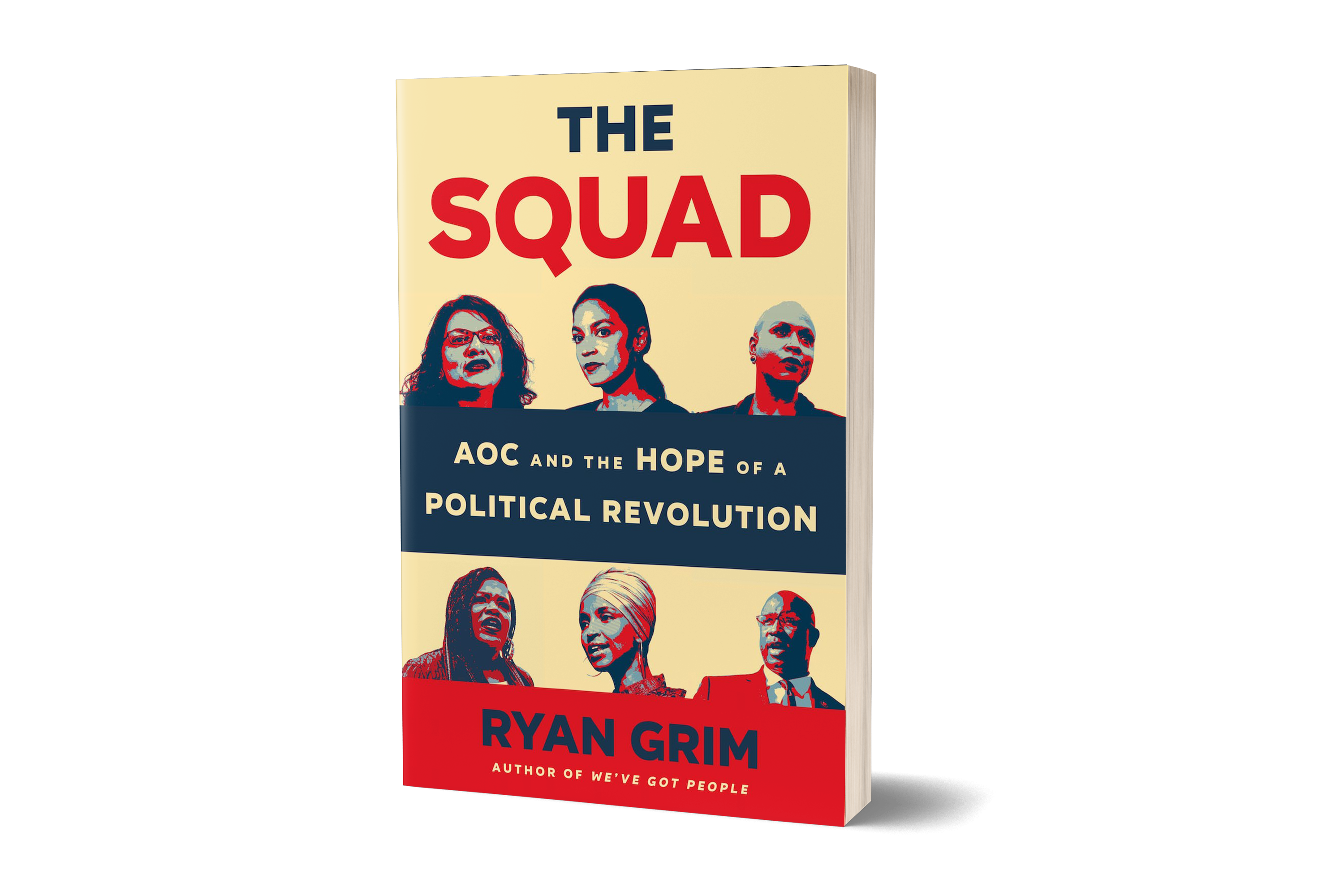

Author and journalist Ryan Grim has spent years covering progressives in Congress, most recently as The Intercept’s D.C. Bureau Chief after nine years with HuffPost. In his new book, The Squad: AOC and the Hope of a Political Revolution (Henry Holt and Company, 2023) Grim traces the rise of, and backlash to, a new progressive movement in U.S. politics. From the 1980s presidential campaigns to the 2018 election to Congress of four progressive women of color dubbed “the Squad”—Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), Ilhan Omar (D-MN), Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), and Rashida Tlaib (D-MI)—Grim shows how various political shifts in the last 40 years have transformed U.S. government and society. Grim spoke with PRA in December about what the Squad and other progressives have recently accomplished, and where they’ve faltered in the face of the Right’s shifting tactics. The Squad follows Grim’s 2019 book, which Naomi Klein called “an essential read”: We’ve Got People: From Jesse Jackson to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the End of Big Money and the Rise of a Movement (Strong Arm Press, 2019).

PRA: So the first question I have is: How has the Right changed tactics since you published We’ve Got People in 2019 and how has that altered the Squad’s approach?

Ryan Grim: The Right, beginning with the rise of AOC and then the rest of the Squad, really zeroed in on these women of color as people that they could elevate and then caricature, and then destroy. They continued to try to do that through George Floyd and now into the Israel-Gaza War, just constantly calling Rashida Tlaib an antisemite and trying to pressure other Democrats to denounce her. There’s a real divide-and-conquer strategy, where a lot of center-left Democrats absorb their understanding of the left wing of the Democratic Party through right-wing media and denounce their own colleagues. That has actually had the effect of, in some ways, driving the Squad closer to other Democrats, because they’re constantly in a defensive posture.

Regarding shifts in left-wing strategy, you also write that some immigrants’ rights activists in the Obama era “began linking immigrant justice with other efforts to combat oppression” in your 2019 book.[1] How useful was that shift and how has it affected other progressive movements?

It’s going to be really interesting, looking back on this history, maybe in five or ten years, if Democrats do end up just completely throwing immigrant justice groups under the bus. They seem like they want the Republicans to force their hand to do a crackdown. I think [immigrants’ rights groups] did as well as they could, and they did successfully push immigrant justice into the center of the Democratic Party’s agenda, which [the Party] then cynically weaponized against Donald Trump, accusing him, accurately, of being nativist and xenophobic. Yet they didn’t get any immigration reform done. Dreamers are in a better limbo than they were in before, but it’s still a limbo. The pendulum seems to be swinging backwards. And you have Republicans increasing their vote share among Latino voters. It’s been kind of a wild ride.

In The Squad, you describe the atmosphere in many contemporary progressive organizations as paralyzed by dysfunction. What do you see as the best way to break the cycle of infighting and make meaningful progress on key priorities?

The thing that seems to get people together is something to collectively fight for. If people feel like they’re all in something together and making progress, that’s when you’re able to put your differences aside. The main thing we’ve been seeing is these movements are in retreat. Because one of the things that was disrupting a lot of these organizations is that they have a particular mission and then whatever was hot in the moment, whether it was #MeToo or George Floyd or now Gaza, people would say, This is the burning moral question of our day; we need to reorganize our mission and go in that direction. They’re trying to find ways that you can keep an organization’s mission in place, but also give people the opportunity to do the things they feel morally compelled to do.

So how cohesive and effective has the Squad been as a force within Congress since their election in 2018?

That period is key. It’s the first six months where they’re making their mark and, almost that entire time, they’re getting battered. Ilhan Omar’s getting called an antisemite, Rashida Tlaib’s getting called an antisemite, and they moved to censure Omar on the floor of the House. Then as soon as that was over, there’d be another controversy that their antagonist, Josh Gottheimer [D-NJ], would poke at, and then Democrats would all be getting asked, Do you condemn this thing that Rashida Tlaib or Ilhan Omar just said?—and it really made it so that they’d look up and six months had passed. So [what] they had run on and [planned to] do together didn’t get done, because you’re just on your heels at the same time. You had this wild spectacle where they’re in this relentless war of words with Nancy Pelosi over Trump’s immigration policy, where Pelosi is just ramping up the rhetoric to the point where finally Trump jumps in and essentially says, Yes, Nancy Pelosi’s right. We should send them back, and I bet Nancy would love to pay for their ticket. And that was such a humiliating moment for Pelosi because she’s like, Oh, my God. All right. Now I’ve gone too far; this guy is cheering me on. And it sort of forged [the Squad] into a unit, even if they weren’t one to begin with, because they were all in the trenches together.

They’ve also expanded their ranks. You’ve got people like [Representatives] Delia Ramirez in Chicago, Greg Casar in Austin, Maxwell Frost from Orlando—who I write about and is an interesting case—and Becca Balint in Vermont. You can count up to maybe a dozen members—much safer, if there’s safety in numbers, than just four.

In The Squad, you write of 2019, “Congress was more than two months old and still focused primarily on the question of whether [Ilhan] Omar was anti-Semitic, rather than on any substantive legislative agenda or effort to challenge President Trump.”[2] How does this compare to the current discourse around the war in Gaza?

It really is amazing how much of a microcosm that first six months in 2019 was of this broader fight. It really felt like a way for Democrats and Republicans to kind of abstract away the threat that was represented by the Squad coming to Congress, instead of talking about [issues] on their terms—corporate corruption, Medicare For All, health care crisis, climate crisis, Green New Deal. And we’re doing something similar now with the war in Gaza—rather than talking about the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Gaza, we’ve abstracted it several layers away to just talking about antisemitism on college campuses here in the United States. It does all feel very similar but now playing out on a much bigger stage and scale.

In We’ve Got People, you write, “It was important for [Mitch] McConnell to show that the direct-action pressure campaign [to block Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination] didn’t work… Making public protest feel futile is essential to [the GOP’s] project” (300–301). What have you learned [since then] about how to combat the feeling and the reality that protest is often futile, even when your demands have strong majority support?

Sometimes the lessons are pointing to actual wins, even if they’re momentary ones. I don’t think it’s been really reported before the way that the American Rescue Plan unfolded, where there was so much public anger about the $15 minimum wage getting stripped from it. That [anger] gave the Squad the credibility to tell [Rep. Pramila] Jayapal, and gave Jayapal the credibility to tell [Sen. Chuck] Schumer, and gave Schumer the credibility to tell [Sen. Joe] Manchin that if Manchin tried to strip down the unemployment benefits or shrink the size of the checks that were left in the Plan, the Squad was going to walk. He was left between, I either take this entire bill down, or I capitulate. So he caved. Writing about the reaction to protest and to political insurgency is also a way of showing people that it actually does matter—the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) would not be spending $100 million for nothing. And No Labels would not be organizing against the Squad and the progressive caucus to the tune of tens of millions of dollars if there were no threat to power. You can, in some ways, judge a faction based on how powerful their enemies are. In some ways, what McConnell is doing is an admission that he does have some fear of it.

Reading The Squad, I was struck by the discomfort Ocasio-Cortez seemed to feel when encountering skepticism or hostility from colleagues. It was also “disorienting,” you write, “for people who considered themselves outsiders and agitators to be insiders” (p. 312). What does that discomfort mean for the Left and how can it be neutralized or overcome?

If you can recognize your power and your assets and find yourself on the inside and [remain] connected and rooted with the outside movements that propelled you there, then that’s incredibly powerful. Sometimes, out of fear of being seen as an insider, AOC or others would leave power on the table.

What are three big issues today on which there’s both significant pressure from outside left-wing groups and actual movement inside of Congress?

Israel’s assault on Gaza is reinvigorating [external organizing and internal debate], and the winding down, it seems, of the war in Ukraine is opening up space for a Left-Right coalition that is hostile to American imperialism and had been bubbling up before. [Republican Rep.] Matt Gaetz [thinks] anything in the Western Hemisphere is fair game for the U.S., but he has teamed up with Ilhan Omar on a bunch of efforts to bring troops home from the Middle East and Africa. There’s some energy there on climate. But there sort of isn’t a third one at this point. It’s waiting to be determined: Do labor rights take off? Does anti-trust take off? Police reform seems to have sputtered out on Capitol Hill. Reproductive rights are an issue that the entire Democratic Party is now pretty much united on; the Left is 100% there, but hasn’t really previously made it a central plank. The question is, how hard to fight on it and where?