In November, the country breathed a sigh of relief when then-President Elect Joe Biden appointed a Coronavirus Task Force populated by experts, signaling a return to science and, hopefully, a critical change in managing the pandemic, even as the death toll continued to rise. On his first day in office, Biden enacted a series of COVID-19 related executive orders, including one establishing a federal mask mandate for all federal offices and properties, as well as certain forms of public transit, and incentives for states and localities to do the same.

But these moves also beg the question of who will enforce them and how? And at the same time, Biden is in the midst of shortchanging people on the $2,000 survival payments promised to voters in Georgia while the country faces a looming eviction and foreclosure crisis, unprecedented unemployment, and food insecurity.

As we enter the second year of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. stands at a crossroads. How will we move forward? With more pandemic policing and abandonment of Black, Indigenous, incarcerated, disabled, low-income, and unhoused communities to the ravages of a deadly pandemic? Or with deep investments in community supports, protection, prevention, and recovery?

What follows is an edited excerpt of the COVID19 Policing Project’s report, Unmasked: Impacts of Pandemic Policing, released in October 2020. Its findings offer a cautionary tale around public health enforcement and illustrates the need to pursue a different path forward, beyond policing and organized abandonment of the communities most devastated by the coronavirus pandemic.

— Andrea Ritchie

Unmasked: Impacts of Pandemic Policing

By Pascal Emmer, Woods Ervin, Tiffany Wang, Derecka Purnell, and Andrea J. Ritchie

As of this report’s release in October 2020, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 was approaching a quarter-of-a-million people, many of whom died trapped in jails, prisons, ICE detention centers, and nursing facilities, or from lack of medical care and widespread structural failures in prevention, detection, treatment, and economic support at every level of government.

We are living through multiple intersecting pandemics—the coronavirus pandemic; the unprecedented economic crisis it has precipitated, featuring record unemployment and looming mass evictions; the ongoing pandemic of police violence; and an intensifying climate crisis producing raging wildfires, mudslides, and storms around the globe. Instead of meeting these life-threatening conditions with investments in health, safety, and survival, policymakers have used the pandemic as a pretext for expanding policing, criminalization and surveillance, placing individuals and communities at increased risk of violence, illness, and death.

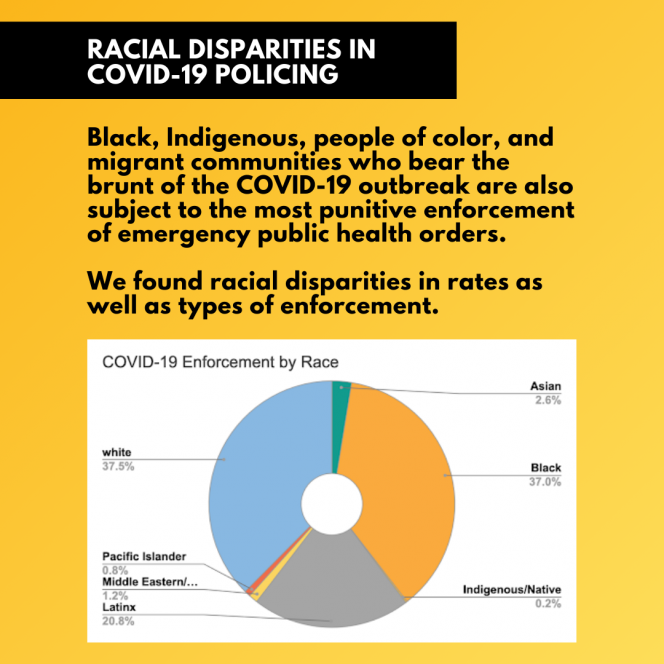

Criminalization is increasingly the default response to every harm, conflict, and need, and the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception.[1] As infection rates rose, jurisdictions across the U.S. and around the world began enforcing emergency “shelter-in-place,” “social distancing,” and quarantine orders through aggressive surveillance and policing tactics, steep fines, criminal charges, and harsh penalties. Consistent with existing policing practices, enforcement has focused on communities hardest hit by both the pandemic and economic crisis it has caused—Black, Indigenous and Brown communities, migrants, essential workers, low- and no-income, unhoused, young, and disabled people—while former U.S. President Trump, police, and white nationalist militias defiantly disregard public health orders and practices with impunity. [2] As the pandemic persisted, and a second, larger wave of infection was predicted, authorities doubled down on policing and punishment by continuing to impose exorbitant fines and offering people financial rewards to turn in community members who violate public health orders instead of reaching out to support them.

Delegating the task of protecting our communities’ health to law enforcement is counterproductive at best, and enables new forms and contexts of criminalization and police violence. Enforcement of mask and social-distancing orders involves police officers—who in many jurisdictions don’t or inconsistently wear masks—violating social distancing guidance to harass, ticket, and take people into custody in jail facilities that have experienced some of the highest infection rates in the country. Even a brief encounter with an officer or short detention in a police car can dramatically increase risk of infection, and that risk increases the longer a person spends in a holding cell or jail where social distancing is impossible, and there is little or no access to soap, water, and sanitizer. In a number of cases that have come to light, officers have enforced public health orders using physical violence, further threatening public health.

Instead of offering our communities the information and support we need to stay safe, policymakers are conflating public health with policing, slashing funding for medical care and social service programs while increasing or maintaining police budgets. The federal government allocated $850 million per state for local law enforcement from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, while offering individuals a one-time $1,200 economic stimulus payment intended to keep a faltering economy alive, instead of long-term income support enabling individuals to survive. Adding insult to injury, in addition to criminalizing non-compliance with public health orders, legislators seized on the pandemic to further penalize abortion, survival, and protest.

In many respects, police enforcement of coronavirus-related public health orders replicates and expands “broken windows” policing, a paradigm and set of policing practices focused on “order maintenance.”[3] The theory was first articulated by right-wing social scientists George Kelling and James Q. Wilson in a 1986 article in The Atlantic. Built on flimsy premises and since largely debunked, broken windows policing has nevertheless taken hold across the U.S. and globally. At its core, broken windows policing labels individuals, behaviors and communities as signs of “disorder” that must immediately be rooted out, policed, and punished on the baseless presumption that, if left unchecked, an escalation of violence will inevitably ensue. The theory specifically identifies youth of color, unhoused people, women standing on corners, street vendors, and drinking in public, among other things, as indicators of disorder that must be removed through enforcement of an ever-expanding list of offenses, criminalizing otherwise lawful conduct in public spaces. Throughout its existence, “broken windows” policing enforcement has disproportionately focused on Black, Brown, queer, trans, unhoused, street vending, and sex trading people and communities, as reflected in stark racial disparities in citations and arrests.

Pandemic policing has now superimposed a new presumption of “public health disorder” on the very people whose mere public presence is already framed as dangerous to the public health and “order” under the “broken windows” framework. This has led to widespread harassment, citation, and physical violence against Black and Brown people in the context of enforcing actual or perceived non-compliance with public health orders, while white people engage in identical behavior, often defiantly and aggressively, with impunity. It has also exposed Black people to harassment, charges and arrests for both appearing masked in public—long considered a broken windows offense—and not wearing a mask in public—a violation of current public health policies.[4]

Our analysis of media reports found multiple cases illuminating these parallels. At the height of enforcement of stay-at-home, social distancing and mask orders, police regularly stopped people for violating public health orders and then charged them with “broken windows” offenses. For instance, in New York City, police were repeatedly observed in predominantly Black working-class neighborhoods approaching people standing outside their homes, ostensibly to enforce mask or social distancing requirements, and then writing tickets for “open container” violations. In contrast, residents photographed NYPD officers in affluent white areas of the city handing out masks as people picnicked.[5]

In Chicago, police officers stationed on street corners in majority-Black and Latinx neighborhoods required people to show ID before being allowed to enter their own residential blocks. While this was justified as a measure to promote social distancing, it was actually an extension of a program to police so-called “criminal loitering” in the area. [6] Conversely, Black, Brown, Indigenous, migrant, disabled, queer, trans, sex working, and unhoused people whom police had initially arrested, cited, or stopped for broken windows offenses (such as disorderly conduct, drug possession, loitering, open container, or other “quality of life” crimes), were then subject to additional charges of violating social distancing, gathering limits, mask-wearing, and curfew mandates.

There is another way, beyond the binary of surveillance and punitive enforcement and abandonment of all public health efforts in a rush to reopen. Through public education; universal, no-cost, accessible, and high-quality health care; widespread dissemination of up-to-date and reliable public health information; safe housing; rent and mortgage cancellation; income support and unemployment benefits; worker protections; and resourcing community-based organizations, credible messengers and individuals, we can provide individuals and communities with the support necessary to protect ourselves, each other, and our communities, now and in the long term.

For more information and to download the complete report, please visit covid19policing.com.

The COVID19 Policing Project, co-founded by Andrea J. Ritchie and Derecka Purnell and housed at the Community Resource Hub, tracks coronavirus-related public health orders and enforcement actions, producing regular updates and policy recommendations relating to policing and criminalization in the context of the pandemic. For more information please visit COVID19policing.com.

Endnotes

- Beth Richie and Andrea J. Ritchie, The Crisis of Criminalization: A Call for a Comprehensive Philanthropic Response, Barnard Center for Research on Women, Report No. 9, 2017, http://bcrw.barnard.edu/wp-content/nfs/reports/NFS9-Challenging-Criminalization-Funding-Perspectives.pdf.

- Robyn Maynard and Andrea J. Ritchie, “Black Communities Need Support, Not a Coronavirus Police State,” Vice, April 9, 2020, https://www.vice.com/en/article/z3bdmx/black-people-coronavirus-police-state.

- Andrea Ritchie, “Black Lives Over Broken Windows: Challenging the Policing Paradigm Rooted in Right-Wing ‘Folk Wisdom,’” The Public Eye, Spring 2016, http://www.politicalresearch.org/2016/07/06/black-lives-over-broken-windows-challenging-the-policing-paradigm-rooted-in-right-wing-folk-wisdom.

- Blake Montgomery, “D.C. Police Charged Demonstrators With Wearing Masks Even Though Coronavirus Guidelines Require Them,” Daily Beast, June 2, 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/dc-police-charged-demonstrators-with-wearing-masks-even-though-coronavirus-guidelines-require-them.

- Poppy Noor, “A tale of two cities: how New York police enforce social distancing by the color of your skin,” The Guardian, May 4, 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/04/coronavirus-new-york-police-enforce-social-distancing.

- Pascal Sabino, “Chicago Police Required ID To Access West Side Blocks To Curb Coronavirus, But ACLU Says Move Might Violate Rights,” Block Club Chicago, April 5, 2020, https://blockclubchicago.org/2020/04/05/chicago-police-required-id-to-access-west-side-blocks-to-curb-coronavirus-but-aclu-says-move-might-violate-rights/.