Epicenter: Chicago

Introduction

In many ways, all eyes are on Chicago. The city increasingly finds itself at the epicenter of multiple discourses of violence and safety – from hubristic Presidential tweets claiming federal intervention is necessary to address Chicago’s murder rate, to hand-wringing national headlines calling the city the “gang capital” of the United States,1 to threats to send migrants seeking refuge at the border to Sanctuary Cities like Chicago, to everyday corner conversations about the latest shooting, whether by a police officer or community member.

Chicago is also a hub of resistance, fighting back against a number of national trends, including racial profiling, police violence, discriminatory “stop and frisk” programs, intensified gang enforcement and surveillance, criminalization of poverty, targeting of migrants, continuing residential segregation, gentrification, attrition of public housing, and privatization of public education and public services. Movements across the country are looking to Chicago’s uniquely intersectional organizing and recent wins on several fronts, including:

- securing reparations for survivors of police violence,

- re-establishment of a trauma center on the city’s South Side,

- Dante Servin’s forced resignation two days before a termination hearing. Unfortunately, by allowing Servin to resign the Chicago Police Department preserved his right to receive a full pension. This became the subject of a campaign by several organizations to remove Servin’s pension and reinvest it in Chicago State University, a predominantly Black institution,

- unseating former District Attorney Anita Alvarez in the wake of the police murder of Laquan McDonald and subsequent cover-up,

- a successful lawsuit forcing the City to enter into a consent decree focused on one of the nation’s most deadly and discriminatory police departments, and,

- a spirited youth-driven campaign challenging investment in building a $95 million police training academy in a community devastated by decades of residential segregation, structural economic abandonment, and school and mental health facility closures.

The midwestern Democratic stronghold has thus become something of a bellwether. Politicians of all stripes across the country are using the Windy City’s woes as justification for “tough on crime” measures, and have been carefully monitoring former Mayor Rahm Emmanuel’s political fortunes as he navigated debates, vigorous protests, and advocacy campaigns around policing, gun violence, immigration enforcement, gang policing, public education, and city budgets.

Now, in the wake of Emmanuel’s unexpected declaration that he would not run for a third term, Chicago is facing a new future under a new Mayor and newly configured city council on hotly contested political terrain.

Under the banner “Free the City, Heal the City,” Chicago’s cross-sectoral and intergenerational organizing community is calling on the new city leadership to adopt a whole new politic – one that conclusively rejects privatization of public goods, disinvestment from low-income communities and communities of color, and reliance on policing and criminalization as the primary response to social problems and substitute for social services and social goods. There is much we can learn from Chicago’s journey to this moment and the visions for the city that are emerging during this transition.

Andrea J. Ritchie, in collaboration with Black Lives Matter Chicago.

Graphics: Iván Arenas

Images: Love & Struggle Photography

Neoliberalism in Progressive Clothing

Chicago has long led a national trend of promoting and implementing neoliberal policies under the leadership of purportedly progressive city officials – a trend that is also notably in evidence in places like New York, Baltimore, Los Angeles, Houston, and Detroit. As long-time Chicago organizer Mariame Kaba explains, “policies Rahm [Emmanuel] pushed and tried to implement are so emblematic of what people mean when they talk about neoliberal politics. He was 100 percent about using the state to remake communities in favor of those with resources over those without. At every opportunity, he favored privatizing the commons.”2 In just a few words, Kaba captures the elusive concept of neo-liberalism, a set of policies rooted in the infamous Chicago School of Economics that have swept the nation and the globe over the past five decades - for which Chicago is both epicenter and exhibit A.3

Neoliberalism – a term widely used but not widely defined – at its most general refers to a collection of economic and social policies which proliferated in the U.S. under the Reagan administration (most popularly known then as “Reaganomics”) and globally (commonly referred to as “structural adjustment programs” imposed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund on nations of the Global South) over the past five decades. It serves as shorthand for shredding social welfare programs, privatization of public institutions and services, elimination of government regulation, and redistribution of resources into the hands of corporations and wealthy elites, all in the name of “fiscal responsibility.”

Ruthie Gilmore, Director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics at the City University of New York Graduate Center, has dubbed this process “organized abandonment,”4 while in the context of Chicago researchers Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper call it a “war on neighborhoods.”5 Whatever the moniker, the aftermath of neoliberalism looks the same: increasingly precarious employment, housing, health care, and care economies for a growing proportion of the population, hitting low-income communities of color and people already struggling to survive the hardest.6

Although neoliberalism depends on widespread internalization of the notion of “color-blind” operation of free markets, these outcomes necessarily fall unevenly along racial lines.7 They also exacerbate existing gender disparities, as the state targets social welfare programs essential to the survival of people experiencing the highest poverty rates in the United States – Native women, Black women, Latinxs, and people with disabilities. Additionally, many of the responsibilities downloaded by the state onto individuals and communities represent gendered labor, placing additional burdens on low-income women of color.8

The imposition of neoliberal policies is facilitated by cultural promotion and internalization of myths of “individual freedom” and “individual responsibility” that divide individuals into categories of “deserving” and “undeserving” without any regard for the ways in which structural racism and other systemic forms of discrimination and exclusion shape individual choices and life chances. Racialized communities are scapegoated based on projected and perceived moral failings without any systemic analysis of the ongoing impacts of long legacies of colonialism, slavery, segregation, racism, ableism, and patriarchy.9 Such myths are promulgated by right wing politicians like the current President, whose spokesperson Sarah Huckabee Saunders describe Chicago’s “crime problem” as “driven by morality,”10 as well as by politicians upheld as paragons of progressive politics – including former President Barack Obama, who continues to blame young Black men for their choices rather than address the conditions under which they struggle to survive,11 and who deported a record number of people by creating a narrative of “deserving” families and undeserving “felons.”12

While generally associated with fiscally and socially conservative forces, politicians who portray themselves as socially progressive, are in fact increasingly advancing the agenda of the Right through neoliberal policies and practices.

Neoliberalism’s Right-Wing Roots

In Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of a Prison State, queer theorist Stephen Dillion characterizes neoliberalism as “a school of thought and a set of policy recommendations that aims free the market from state constraints to give free rein to private profit by gutting public funding for social services, undermining union organizing, eliminating environmental, labor, health and safety regulations, price and wage controls, and privatizing public resources and institutions.” Ultimately, he concludes, neoliberalism operates on a logic that “prioritizes the mobility and proliferation of capital at all costs.”13

Created by a transatlantic association of economists starting in the 1930s, including Friedrich Hayek, Karl Popper, Henry Simons, Ludwig von Mises and Milton Friedman,”14 neoliberalism is promoted by politicians and think tanks theorizing the fiscal irresponsibility and autocratic nature of state collectivization of resources to provide for the common good. It emerged at the same time as, and in service of, widespread consolidation of power in the hands of transnational capital.15

But neoliberalism is far from a purely economic project. Neoliberalism evolved in response to domestic and global challenges to colonialism, racial capitalism, and structural discrimination mounted by anti-colonial, civil rights and Black power movements in the early 60s and 70s. As organized workers and communities of color in Chicago and in dozens of other cities across the country, including Los Angeles, Detroit, Newark, and Baltimore, called attention to and mounted effective challenges and resistance to structural racism and exclusion in access to employment, public and affordable housing, education, infrastructure and social benefits such as welfare, neoliberal policies and ideologies were deployed to bolster and maintain existing racial relations of power. Black people continued to be excluded from institutions, social programs, legal protections, and communities, whether explicitly through mob and state violence, or by more insidious means such as redlining and discriminatory eligibility requirements.16 As racial justice movements succeeded in achieving increased access for Black people, the state simply divested from public schools, hospitals, housing, social benefits and entitlements, while demonizing and projecting individual moral failure onto people who accessed them to survive in the wake of structural economic oppression and exclusion and growing deindustrialization.

In Chicago, and across the country, public officials responded to mounting protests and urban rebellions fueled by these conditions by declaring a “war on crime” informed by propaganda declaring dysfunctional “cultures of poverty,” and characterizing the “enemy” in highly racialized and gendered terms. For instance, the federal government’s Moynihan Report claimed that households headed by single Black women were a manifestation of formerly enslaved Black people’s inability to assimilate into white patriarchal mainstream society and a primary source of deviance in Black communities.17 Later, right-wing sociologists such as John Dilulio predicted the rise of a generation of “super predators,” shaped by growing up in “moral poverty,” roving the streets in gangs terrorizing communities.18 While Dilulio prescribed religion as the response,19 politicians painting themselves as progressive, including the Clintons and 2020 Presidential candidate Joe Biden, adopted a militarized “law and order” agenda rather than one which addressed economic conditions of widespread poverty and unemployment in Black communities and ongoing legacies of structural exclusion in housing, education, and public health. These tropes under-girded implementation of the 1994 Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act championed by Biden and the Clintons, which created hundreds of new federal crimes, imposed harsh “three strikes” penalties, and poured resources into law enforcement-based responses to everything from violent crime to domestic violence to drug offenses.20

The result: demonization and punishment of Black youth, Black mothers, and Black families through aggressive surveillance, policing, and incarceration while simultaneously divesting from Black communities. As researchers Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper observe in Chicago’s predominantly Black West Side Austin neighborhood, “the ‘bad choices’ of Austin residents are used to explain away huge gaps in wages, school quality, and investments in development. Meanwhile, the residents of advantaged areas…are often immune to criminalization, a fact that allows them to make their own bad choices – from using drugs with near immunity to more serious, white-collar crimes – without ever facing life-altering consequences.”21

Neoliberalism, and its constant companion, the “law and order agenda,” are thus deeply rooted in and advance right wing economic, political and social philosophies. They share dichotomous constructions of the world into the innocent, deserving, homogeneous “we,” and a racialized, dangerous, criminal, immoral, and undeserving “other,” mobilized to produce fear – of being “overrun,” deposed from positions of power, or of rebellion or physical attack.22The “classification of specific persons to the ‘we’ or the ‘others’ must be done via authoritative action, e.g. by blaming the ‘others’ for crimes.”23Neoliberalism deploys racially coded language like “get tough on crime” and “welfare handouts” to “reassert[] tropes of Black violence and laziness,” invoking “centuries-old racist themes: the criminal Black predator and the unqualified (presumably ‘lazy’ and underserving) Black worker.”24

Neoliberal logics also operate on the level of gender and sexuality, as embodied through racialized expectations and narratives of gendered relations of power. While superficially framed as promoting privacy and “individual freedom” from state regulation, neoliberalism attaches tremendous social importance to the lived realities of gender and sexuality, making them targets of cultural and policy interventions designed to bolster neoliberal agendas.

For instance, in order to ensure effective operation of neoliberalism, the stable order of the heterosexual reproductive family is essential in the face of state retrenchment – strong heteropatriarchal families, in which a male breadwinner earning a higher income supports a woman who is charged with reproductive and care labor for nuclear and extended family members in exchange for subsistence, become a substitute for state support. This produces a “push toward neoliberal familialism,” requiring compliance with racialized sexual and gender norms.25For instance, the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation advanced by former President Bill Clinton explicitly promoted marriage in the face of sharp slashes to entitlements, mobilizing a larger narrative of Black women’s promiscuity, dysfunctional family structures, and out of control reproduction to justify cuts and caps to benefits and forced compliance with sexual and gender norms.26

The relationships between neoliberalism’s social and economic projects thus “invoke a range of social relations including those of gender, race, sex, and nation.”27Ultimately, neoliberalism requires the establishment of racialized gender categories, and all who deviate—by raising a family without a male spouse, by relying on social entitlements, or by engaging in sexual or gender expressions outside of a racialized heteropatriarchal norm—are punished and deemed “undeserving” of social goods.28 Discipline and punishment for what are characterized as individual shortcomings, failures, and immorality is thus an essential feature of both explicitly right wing policies and their neoliberal counterparts. In this way, neoliberal narratives and policies paved the way for mass criminalization and mass incarceration.

The Cult of Criminalization

As Beth Richie and I argue elsewhere, criminalization is framed as a natural and neutral social and political process by which society determines, through passage of criminal laws, which actions or behaviors will be punished by the state to address individual or collective injury. Yet decisions about what kinds of conduct to punish, by who, how, and how much, are very much political choices, made in service of existing relations and structures of power.29 Police officers saturate public transit facilities to catch people who can’t pay fares under $5 while leaving people who swindle millions in taxes in peace. A neighborhood in which people struggle to survive is heavily policed as a “high crime area,” while Wall Street, arguably one of the highest crime areas of the country, is not. Even killing another human being is not universally criminalized – drone assassinations ordered by a President are deemed acts of patriotism and national security, police killings of people they are sworn to serve and protect are deemed justified, and the right to kill in self-defense is selectively bestowed on the George Zimmermans of the world while being denied to Black women like Marissa Alexander or Liyah Birru who defend themselves and their children against violence and abuse in their homes.

As Aislinn Pulley of the Chicago chapter of Black Lives Matter argues, what is labeled “criminal” is, in fact, the product of neglect and divestment from communities, criminalization of activities seen as characteristic of particular populations, and saturation of targeted communities with police officers armed with an arsenal of criminal offenses and full discretion to harass and criminalize specific populations.

Criminalization extends beyond discriminatory drafting and enforcement of laws and policies to more symbolic – and more deeply entrenched processes of creating categories of people deemed “criminals.” As a result, even as overtly discriminatory criminal laws change, the same populations continue to be targeted through enforcement of “neutral” criminal laws. This process is fueled by widespread and commonly accepted highly racialized, gendered and ableist narratives – whether they are about “thugs,” “crack mothers,” “welfare queens,” monstrous gang members, or “bad hombres” – which are used to fuel a generalized state of anxiety and fear, and to brand people labeled “criminal” as threatening, dangerous, and inhuman. In this context, violence, banishment and exile, denial of protection, and restrictions on freedom, expression, movement, and ultimately existence of people deemed “criminal” within our communities becomes a “natural” response.

Chicago’s infamous police torture scandal, in which a police commander fresh from the Vietnam War, equipped with instruments of torture deployed against “foreign enemies,” turned them against actual and purported gang members framed as “domestic enemies” in the “war on crime” for a period spanning over two decades, sending hundreds to prison and death row based on coerced confessions, with the tacit encouragement of the police department, the prosecutor’s office, the judiciary, civilian oversight agencies, and city officials right up to former Mayor Richard Daley, who notoriously used a confession he was aware was secured by torture to prosecute a man accused of killing two police officers, is but one particularly egregious example of the consequences of criminalization.30The more recent discovery of the disappearance of thousands of people arrested by the Chicago Police Department into the bowels of the Homan Square facility to be interrogated while being denied counsel, is another.31 Both practices, allowed to continue for decades as open secrets, represent prime examples of how criminalization normalizes the most egregious of abuses under “progressive” administrations claiming to simply be upholding the rule of law.

Criminalization, normalized as an objective process, ultimately, has become the default response to the impacts of organized abandonment, pushing entire communities into the maw of mass incarceration, detention, and deportation.32Communities, schools and health care facilities devastated by neoliberal policies are flooded with police, and shelters which take the place of affordable or subsidized housing, or drug treatment programs offered as the only alternative to incarceration, become sites of discipline.33The criminal legal system “has directly taken over the provision of myriad functions of the social state from social services to mental health… [and] the specter of criminal prosecution reaches further and further into the mundane messes of school or domestic disputes, small-scale drug possession, child truancy, or non-compliance with psychiatric medication.”34

In this context, “broken windows policing,” developed by conservative theorists James Q. Wilson and George Kelling as a response to the increasingly visible evidence of economic devastation wrought by neoliberal policies, is now touted by progressives as a “common sense” response to mounting “disorder” in urban areas, trading on images of unemployed youth of color “hanging out on the corner,” homeless people and panhandlers, and people engaged in the sex trades and other criminalized survival economies, as signs of “disorder” and precursors to crime who must be surveilled and rounded up to make way for the new neoliberal order.35Laws prescribing punishment for everyday activities as simple as standing on a corner or riding a bicycle on a sidewalk, as well as the predictable consequences of poverty, proliferate in service of this broader agenda.36To give just one example of how these seemingly innocuous laws area applied, an examination of the Chicago Police Department’s practice of ticketing cyclists found that more than twice as many tickets were being written in Black and Latinx communities than white ones.37

“Broken windows” policing has a long history and deep roots in Chicago: its gang-related loitering ordinance was passed in 1992 to allow police to “clean up the streets” by targeting groups of Black youth in public spaces. During the three years it was in effect, 40,000 predominantly Black and Latinx people were arrested under the law. Its widespread enforcement had no effect on reducing violence, in fact, gang-related homicides went up by 27% during this period. The ordinance was ultimately the subject of a successful Supreme Court challenge on the grounds that it allowed for indiscriminate targeting of Black youth,38only to be reinstated in a slightly different form, under which severe racial disparities in enforcement persist: 98% of people subject to the law in 2014 were Black or Brown.39A more recently passed “prostitution-related loitering” ordinance, enacted in 2018, offers police another tool to target Black and Brown communities while policing the lines of gender and sexuality.40

Image: Bruce Leighty / Alamy

Ultimately, neoliberalism, in Chicago and across the country, represents a shift from a welfare state to a carceral state,41producing mass surveillance, mass criminalization and mass incarceration as a substitute for structural change required to redress the nation’s long histories of racial, gender and economic oppression. Mayor Rahm Emmanuel’s budget priorities clearly reflected this approach: “we’re going to increase our investments with more police officers. Every other decision will be made around that priority.”42 Indeed, the substitution of policing and criminalization for social goods and services is a central feature of neoliberalism, yet the direct connection between the two is often obscured.43

As Ruthie Gilmore, the CUNY professor, points out, the rise of the neoliberal state has “depended on mass criminalization to mark certain people as ineligible for, as well as undeserving of, social programs.”44Criminalization serves as a shield behind which neoliberal agendas can advance, hidden behind universally palatable messages of “fighting crime” and creating “safer neighborhoods,” while simultaneously diverting resources from meeting community needs, and effectively undermining arguments for change with the specter of increased violence, crime, and harm to those deemed both “innocent,” and “deserving.”

Neoliberalism covers up its devastating impacts – declining school enrollment and high unemployment, increased homelessness and participation in criminalized survival economies, increased migration, and a growing population of people whose physical and mental health needs are not met – by labeling them a “crime problem,” produced by individual failure and immorality, often projected onto entire “dysfunctional” communities and racial groups. For instance, “Reaganomics,” which promoted deep cuts to social safety nets, and particularly welfare, as a growing number of people of color began to access these programs as jobs disappeared, was normalized through promotion of the racial caricature of the duplicitous, materialistic, and freeloading “welfare queen,” who simultaneously became the target of criminalization not only for “welfare fraud,” but for all manner of offenses related to poverty, parenting, promiscuity, and presence in public spaces, illustrating how racially gendered cultural tropes developed in service of neoliberalism simultaneously fuel criminalization and right wing economic agendas. Such policies and practices are not limited to right wing politicians – Clinton’s efforts to “end welfare as we know it,” for which none other than Emmanuel served as an advisor, represented “neoliberalism with a Democratic face,” continuing to trade in racialized and gendered narratives to fuel criminalization of Black women.45

Criminalization is thus an integral part and key weapon of neoliberalism. It is also as a primary mechanism for advancing right wing agendas. It is successful in both contexts in branding entire groups of people including in liberal and progressive minds as deserving of punishment and exclusion, and as unworthy of social goods.

We see how effectively these dichotomies are mobilized in the context of immigration – leaving so-called progressives negotiating increasing criminalization of migration and border enforcement in exchange for relief for a small group of “innocent,” non-criminalized migrants deemed worthy of relief. The same dynamics take place within our cities, encouraging us to trade programming for people who fit into narrow frameworks of of innocence and individual redemption – often offered through private, corporate, religious or non-profit interests for increased policing, punishment, and taxing of low-income communities of color, while avoiding a shift in the overall balance of power and structural exclusion.

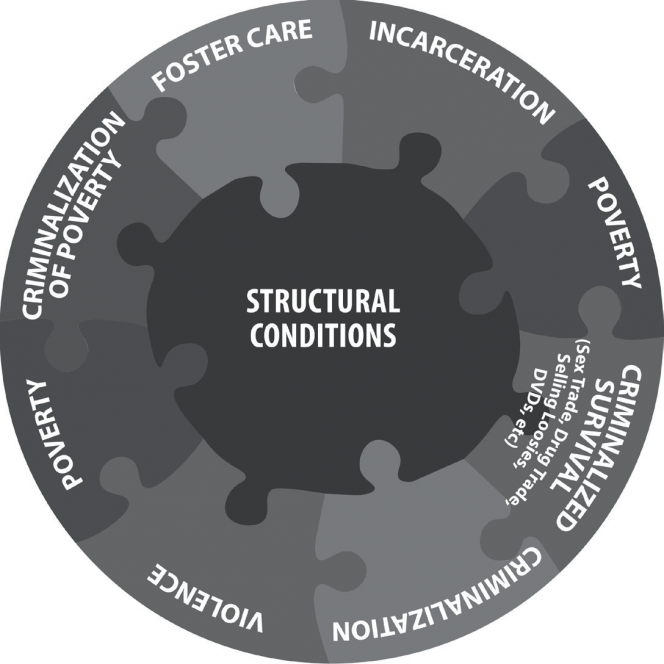

Not only are criminalized populations the first to be shut out of shrinking social programs, job markets, and society as a whole under this logic, but they are increasingly subjected to punitive fines, fees, bail, costs associated with incarceration and e-carceration.46Neoliberalism thus unleashes a vicious cycle of poverty and criminalization that further fuels the flow of resources out of low-income communities and into the hands of government, corporations and business interests.

A Vicious Cycle Of Poverty And Criminalization

The notion that municipalities derive a significant portion of their revenue from fees and fines imposed on criminalized communities of color catapulted into the national consciousness following the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigation of the Ferguson Police Department in the wake of the police killing of Mike Brown in August of 2014.47This trend of local governments mobilizing “systems that were made to ensure the public safety as revenue generators”48is not new. It is representative and a natural consequence of neoliberal policies which favor low taxation rates for the wealthy and hefty tax breaks for developers, corporations and powerful institutions, leaving municipalities to generate revenue through taxation of criminalized communities by way of fines and fees.

The City of Chicago raised over $350 million in fines, fees and forfeitures in 2016.49Meanwhile, this taxation of criminalized communities creates a vicious cycle driving them further into poverty and often into prison. The consequences for individuals and communities can be devastating, bankrupting hard working people whose inability to pay parking tickets or traffic fines snowballs into insurmountable debt, leading the city to seize what few assets they have, interrupt their ability to earn income, and ultimately, drive them to desperate measures. According to a Mother Jones investigation, the 3 million tickets for parking, red light violations, expired plates or failure to display a city sticker issued in Chicago every year – more, per adult, than Los Angeles or New York City “brought in nearly $264 million in 2016, or about 7 percent of Chicago’s $3.6 billion operating budget.”50

The impacts of the ticketing, like everything else in Chicago, fall unevenly. “Eight of the ten ZIP codes with the most accumulated ticket debt per adult are majority Black.” These communities “account for 40% of all debt, though they account for only 22% of all tickets issued in the city over the past decade,” largely because low-income residents are less likely to be able to pay tickets and more likely to incur fines for non-payment, vehicle towing and impound as time goes on.51

Once in ticket debt, individuals are barred from municipal jobs, contracts, licenses, grants – and even jobs as Lyft or Uber drivers – that would enable them to pay off the debt. They may lose their driver’s license, and their car may be immobilized by city employees deploying a device known as the “Denver boot.” Forced to choose between meeting basic needs and paying ticket debt, and facing losing access to vehicles in a city where public transit can require hours-long commutes to and from school and jobs, individuals and families are pushed into more and more dire circumstances. Declaring bankruptcy out of desperation often doesn’t solve the problem, and the City is working to undermine even the minor relief individuals can obtain by initiating bankruptcy proceedings to reclaim their vehicles.52

The use of traffic and parking enforcement to fill city coffers while driving communities further into poverty and structural exclusion is but one of many examples of how neoliberal policies and criminalization are intertwined and operate in service of one another, in Chicago and beyond.

Neoliberalism, Chicago-Style

In Chicago, neoliberal policies have taken the form of seizure of Mayoral control over the public education system, followed by the most massive closure of public schools in U.S. history over 50 public schools in 2013, affecting 30,000 40,000 students in the city’s predominantly Black and Brown West Side,53and over 150 public school closures or restructuring since 2001 – 88% of students affected are Black, 10% are Latinx, and 94% are low-income.54Public school closures have been accompanied by the proliferation of private charter schools, and siphoning of real-estate taxes from schools in low-income neighborhoods into the hands of private downtown developers.55Emmanuel’s neoliberal approach also manifested through the closure of half of the city’s mental health clinics and privatization of mental health care.56 Ongoing mismanagement of public housing and decline of affordable housing increased during his tenure – again mirroring national trends resulting in the disappearance of a quarter of a million public housing units since the early 2000s.57

Not coincidentally, each of these sectors has simultaneously seen a dramatic increase in policing and criminalization, which is in turn justified by narratives of increasingly out of control violence in communities which have been abandoned by the city and subject to deeper impoverishment through criminalization.

However, disinvestment, concentration of resources in the hands of private interests, deep cuts to public education and social programs, and entrapment in a vicious cycle of poverty – not personal failings and racial pathologies are the drivers of violence, whether it is state, structural, economic, or interpersonal violence, in Chicago’s communities and across the country. As Kaba puts it, “You should blame Emanuel for enabling systemic and structural violence that have been unleashed through his policies on to poor communities of color. But this is not the narrative about violence in Chicago that is uplifted nationally. It should be. Interpersonal violence mirrors structural violence.”58

Chicago remains nearly as segregated as it was 50 years ago, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. launched a campaign for desegregation of the city’s neighborhoods. Its population – roughly one third white, one third Latinx, and one third Black live in distinct parts of the city. According to the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Institute for Race and Public Policy, “where people live shapes their proximity to quality public education, the availability and variety of public amenities, their access to quality healthcare facilities and social services, their exposure to or insulation from pollutants and other environmental hazards, and their immediate access to jobs, among other factors associated with well-being and social mobility.”59It also shapes their experience of policing, criminalization, and safety.

The neighborhoods with the highest reported violent crime according to Chicago Police Department60are the neighborhoods experiencing the most devastating impacts of neoliberal policies.61

Localized Resistance to Neoliberal Agendas

There is much to be learned from Chicago organizers about resistance in a time of state seizure by the Right and cooptation of “the resistance” by “progressives” advancing neoliberal agendas.

Long-time organizer Kaba points to an important lesson of Chicago organizing: “It isn’t about Democrats versus Republicans. Chicago is a democratic city; there is only one Republican on the city council. I think a lesson is to focus on issues instead of focusing on political parties.”62In other words, the goal should be to fight implementation of both right-wing ideologies and neoliberal policies, and the criminalizing cultural norms that underlie them both, as well as their vast and far ranging ramifications, no matter the source.

During the 2019 Mayoral election, the Grassroots Collaborative, a coalition of 11 Illinois labor and community organizations, issued a policy platform to #ReimagineChicago. Its comprehensive set of demands and recommendations include:

- reinvestment in neglected Black and Brown communities,

- fully funded public schools,

- an elected school board,

- universal public childcare,

- reopening public mental health clinics and increased investment in community-based health care, including mental health services,

- expanded public, affordable housing, and prevention of homelessness,

- increased transit access,

- an aggressive job creation program,

- $15/hour minimum wage,

- increased protections for low-wage workers,

- increased taxation of wealthy individuals and corporations,

- redistribution of revenue from real-estate taxes, and

- diversion of expenditures on policing into community needs.63

Central questions for the new Mayor and City Council include

- how they plan to invest in communities,

- what they will do to eliminate the security state,

- how they will rebuild the mental health and education infrastructure of the city,

- what they will do to interrupt the flow of real-estate tax dollars away from schools and services in low-income neighborhoods into downtown developments that don’t benefit communities,

- how they will demonstrate a commitment to affordable housing, and

- what they will do to bring Chicago’s violent police force under control.

While the rest of the country is looking toward the 2020 election cycle for an opportunity to ask these questions on a national scale, Chicago activists are pointing out that while elections are important points of intervention and opportunities to collectively raise and debate these questions, electoral organizing alone is far from sufficient to contest neoliberal agendas. The R3 Coalition (Resist, Reimagine, Rebuild), which brings together many of the city’s activist communities, organizers, unions, and progressive academics, is calling for a movement to “Free the City, Heal the City” beyond the election. While not directly affiliated with the national Freedom Cities campaign started by BAJI, ENLACE and the Ella Baker Center, or the campaign of the same name subsequently launched by the ACLU, the R3 Coalition is inspired by the concept of a Freedom City, by the Right to the City movement which emerged in the 2000s in response to the wave of neoliberal policies in cities like New York and Miami, and by a global movement toward what has been described as “radical municipalism,” in which communities work through and beyond electoral politics toward radical democracy, local autonomy and self- determination, interdependence, economic and transformative justice. Central to these visions is the interruption of gentrification and displacement, the affirmation of a universal right to access public space free of criminalization, the reclamation of abandoned property in the public trust, and defense of the right to healthy communities.

A number of ongoing campaigns in Chicago and beyond are building toward these goals. For instance, over the past year, a vigorous youth-driven campaign challenged Emmanuel’s plan to build a $95 million dollar police training academy in West Garfield park, one of the communities that has been among the primary sites of organized abandonment under neoliberal policies over the past four decades, as the city’s sole response to the wide-ranging systemic and structural problems with policing and criminalization in Chicago identified by the U.S. Department of Justice and Emmanuel’s own Police Accountability Task Force.64While Emmanuel succeeded in ramming through the plan in his waning weeks in office, the #NoCopAcademy campaign succeeded in challenging the neoliberal underpinnings of the project.65Emmanuel was once again responding to the consequences of disinvestment and increased awareness of its racially disparate impacts with more investment policing and criminalization, all the while reinforcing notions that the issues facing West Garfield Park are rooted in a failure of individual responsibility. Canvassing residents of the West Garfield Park Community, the #NoCopAcademy campaign collected over 1000 recommendations for investment in the community instead of the police training facility, over 50% of which focused on investment in schools and youth.66Similar campaigns to prevent construction of police facilities, jails, and youth detention centers in progressive enclaves like Seattle,67San Francisco,68and Los Angeles,69as well as in St. Louis, MO70have similarly highlighted, confronted and forced public debate about investments in community needs and public goods over investments in policing, criminalization and incarceration under #NoNewJails #CloseTheWorkhouse and #BlocktheBunker campaigns.

The Sanctuary for All campaign,71led by local chapters of national organizations BYP100 and Mijente, and Chicago-based Organized Communities Against Deportation (OCAD), is focusing on divestment from “good” “bad” dichotomies, narratives of individual responsibility, and mechanisms of surveillance. Organizers are calling on Chicago widely acclaimed as having one of the most progressive “Sanctuary City” laws in the country to eliminate exceptions to the city’s Welcoming Cities Ordinance that exclude criminalized migrants from its protections, and to confront and undermine criminalization of all of Chicago’s Black and Brown communities, migrant and U.S. born, through elimination of the Chicago gang database, “broken windows policing,” and criminalization of poverty and survival. Recently, the #ErasetheDatabase component of this campaign scored a significant victory through passage of legislation at the county level calling for an investigation into the uses and harms of the gang database, as well as its permanent decommissioning.72Organizers plan to seek introduction of similar legislation at the city level under the new administration. Youth organizers in Los Angeles73and Providence, Rhode Island74 have similarly challenged the use of gang databases and civil injunctions limiting the freedom of those placed in them, and New York City organizers have taken up the challenge to the NYPD gang database.75

A third thread of Chicago organizing is taking up the consequences of deep investments in policing and criminalization by aggressively pursuing and negotiating a consent decree with the City of Chicago in the wake of the Department of Justice investigation and subsequent withdrawal from oversight following the 2016 federal election.76Led by Black Lives Matter Chicago, Women’s All Points Bulletin, and organizations representing families of people slain by Chicago police, Chicago community-based organizations successfully filed suit seeking meaningful input and oversight over the City’s policing policies and practices. Simultaneously, survivors of Chicago’s infamous police torture and of police violence across the city are coming together through the Chicago Torture Justice Center, secured through the city’s historic reparations ordinance, to build comprehensive visions of police accountability and community safety.77

Organizers are also resisting the neoliberal deregulation of labor markets through the Fight for $15, a campaign that originated in 2012 among Chicago retail and restaurant workers under the rubric of the Workers Organizing Collective of Chicago, which has since spread across the country and around the globe.78The campaign recently succeeded in passing state legislation in Illinois increasing the minimum wage to $15/hour, in spite of Emmanuel’s support of a watered down City level bill offering workers $13/hour. Chicago’s labor movement is now aiming to strengthen the power of local unions, and particularly to rebuild the city’s teacher’s unions, who have been the subject of repeated attacks and retrenchments orchestrated by Emmanuel. Teachers at the city’s charter schools recently went on strike in the context of contract negotiations,79and hospital workers are intensifying their organizing efforts. Chicago teachers’ unions, parents and communities are working to build toward education justice for all Chicago’s youth, regardless of where they live.

Chicago communities are also challenging development projects like the Obama Presidential Center and the Lincoln Yards project80that will benefit from real estate taxes siphoned from low-income neighborhoods to build high priced condos. The Obama Community Benefits Agreement Coalition, made up of 7 South Side organizations, is working to call attention to the communities that will be displaced by the development and to secure an agreement that will promote reinvestment in affected communities.81The question of a Community Benefits Agreement was placed on the ballot in 24 precincts, ensuring that the newly elected representatives from affected wards will be forced to fight for one.

The CBA campaign is but one of many in which communities are demanding accountability – and in some cases reparations from institutions that advance neoliberal policies, including the University of Chicago, one of their primary sources and proponents, as well as a beneficiary of slavery and ongoing gentrification and divestment from surrounding communities. In 2016, organizers successfully forced the University to reinstate a Level 1 trauma center to serve the city’s South Side, reflecting a successful challenge to the health care deserts that exist in so many of Chicago’s Black and Brown communities.82Faculty and students are now turning their attention seeking reparations for the University’s involvement in slavery.83

Finally, communities are organizing to interrupt violence – and calling for greater investment in programs such as violence interrupters and community-building programs such as Mothers Against Senseless Killing (MASK).84

Bringing together the threads of these organizing campaigns, R3 engages communities in conversation beyond the election around questions such as:

- What would Chicago look like if it were a Freedom City? What would make you feel free in Chicago?

- What does transformative justice look like?

- What would have to change in terms of policies and resource allocation to bring these visions into being?

These questions echo those of asked by proponents of radical municipalism: “What does it mean to be a human being? What does it mean to live in freedom? How do we organize society in ways that foster mutual aid, caring and cooperation?”85

In order to answer these critical questions, we need to confront the purposes currently served by criminalization, and ask ourselves how we will undermine the deeply entrenched narratives that fuel it, excise the powerful imperative to punish, exile, and deny the humanity of criminalized people and communities, and foster truly transformative approaches to violence and harm.86We can no longer take as a given the legitimacy of the process of criminalization while tinkering with its more visible problematics and injustices. We need to upend it, and the right wing neoliberal policies that drive it, at their roots, regardless of whether they are advanced by blatant white supremacists or purported progressive politicians. Our survival and liberation depend on it.

Endnotes

- Lincoln Blades, “Trump’s Obsession with Chicago, Explained,” Teen Vogue, July 6, 2017, available at: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/trumps-obsession-with-chicago-explained (last visited April 30, 2019).

- “Social Movements Brought Down Rahm Emmanuel – Now They Can Transform Chicago,” In These Times, September 18, 2018, available at: http://inthesetimes.com/article/21426/rahm_emanuel_mariame_kaba_protest… (last visited September 18, 2018).

- Stephan Pühringer & Walter O. Ötsch, “Neoliberalism and Right Wing Populism: Conceptual Analogies,” Forum for Social Economics, 47:2, 193-203 (2018); Michael Omi and Howard Winant, “How Colorblindness Co-Evolved With Free-Market Thinking,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Organized Abandonment and Organized Violence: Devolution and the Police,” lecture at the Humanities Institute at the University of California Santa Cruz, 11.9.15, available at: https://vimeo.com/146450686 (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper, The War on Neighborhoods: Policing, Prison and Punishment in a Divided City, Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2018.

- Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Michael Omi and Howard Winant, “How Colorblindness Co-Evolved With Free-Market Thinking,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- Elizabeth Bernstein, Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of Freedom, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018, 171; Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013); Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Jean Hardisty, “From the New Right to Neoliberalism: The Threat to Democracy Has Grown,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Barnard Center for Research on Women, “What is Neo-Liberalism?” available at: http://sfonline.barnard.edu/gender-justice-and-neoliberal-transformatio…; Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013); Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013); Sandra K. Soto, “Neoliberalism and Attrition in Arizona,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013). Notably, Bernstein and Jakobsen point to the U.S. backed overthrow of socialist Salvador Allende and imposition of the autocratic Pinochet regime in Chile as one of the origin stories of neoliberalism.

- Lincoln Blades, “Trump’s Obsession with Chicago, Explained,” Teen Vogue, July 6, 2017, available at: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/trumps-obsession-with-chicago-explained (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Derecka Purnell, “Why Does Obama Scold the Black Boys?,” NY Times, February 23, 2019, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/23/opinion/my-brothers-keeper-obama.htm… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Adrian Florido, “Immigration Advocates Challenge Obama’s ‘Felons Not Families’ Policy,” NPR, available at: https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500264042/immigration-advocates-challeng… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Stephen Dillion, Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of a Prison State (Durham, N.C.: Duke Univeristy Press, 2018).

- Stephen Dillion, Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of a Prison State; Jean Hardisty, “From the New Right to Neoliberalism: The Threat to Democracy Has Grown,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Stephen Dillion, Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of a Prison State; Jean Hardisty, “From the New Right to Neoliberalism: The Threat to Democracy Has Grown,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper, The War on Neighborhoods: Policing, Prison and Punishment in a Divided City, Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2018; Institute for Race and Public Policy, A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report, 2017; Natalie Y. Moore, The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation, St. Martin’s Press 2016; Michael Omi and Howard Winant, “How Colorblindness Co-Evolved With Free-Market Thinking,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Whet Moser, “Housing Discrimination in America Was Perfected in Chicago,” Chicago Magazine, available at: https://www.chicagomag.com/city-life/May-2014/The-Long-Shadow-of-Housin… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016, 59; Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, .

- John Dilulio, “The Coming of the Superpredators,” The Weekly Standard, November 27, 1997, available at: https://www.weeklystandard.com/john-j-dilulio-jr/the-coming-of-the-supe… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Ibid.

- Andrew Kaczynski, “Biden in 1993 speech pushing crime bill warned of ‘predators on our streets’ who were ‘beyond the pale,”’ CNN.com, available at: https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/07/politics/biden-1993-speech-predators/ind… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper, The War on Neighborhoods: Policing, Prison and Punishment in a Divided City, Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2018, 24.

- Stephan Pühringer & Walter O. Ötsch, “Neoliberalism and Right Wing Populism: Conceptual Analogies,” Forum for Social Economics, 47:2, 193-203 (2018).

- Stephan Pühringer & Walter O. Ötsch, “Neoliberalism and Right Wing Populism: Conceptual Analogies,” Forum for Social Economics, 47:2, 193-203 (2018).

- Michael Omi and Howard Winant, “How Colorblindness Co-Evolved With Free-Market Thinking,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- Elizabeth Bernstein, Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of Freedom, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018, 60, 65; Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Kaaryn S. Gustafson, Cheating Welfare: Public Assistance and the Criminalization of Poverty, New York, NY: NYU Press, 2011.

- Elizabeth Bernstein and Janet Jakobsen, “Introduction: Gender, Justice and Neoliberal Transformations,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Barnard Center for Research on Women, “What is Neo-Liberalism?” available at: http://sfonline.barnard.edu/gender-justice-and-neoliberal-transformatio…

- Andrea J. Ritchie and Beth E. Richie, The Crisis of Criminalization: A Call for a Comprehensive Philanthropic Response, New Feminist Solutions Series No. 9, Barnard Center for Research on Women, 2017.

- Joey Mogul, “Lawyer for Chicago Torture Victims: A Model for Responding To Police Brutality,” Time.com, May 12, 2015; Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, “Timeline of the Burge Case,” https://www.chicagotorture.org/?page_id=92(last visited April 30, 2019).

- Spencer Ackerman, “The disappeared: Chicago police detain Americans at abuse-laden ‘black site,’” The Guardian, February 24, 2015, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/feb/24/chicago-police-detain-a… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Andrea J. Ritchie and Beth E. Richie, The Crisis of Criminalization: A Call for a Comprehensive Philanthropic Response, New Feminist Solutions Series No. 9, Barnard Center for Research on Women, 2017

- Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013).

- Andrea J. Ritchie, “Black Lives Over Broken Windows,” The Public Eye, Spring 2015.

- Andrea J. Ritchie, “Black Lives Over Broken Windows,” The Public Eye, Spring 2015.

- Mary Wiesnewski, ‘Biking while black’: Chicago minority areas see the most bike tickets,” Chicago Tribune, March 17, 2017.

- Dorothy Roberts, “Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of OrderMaintenance Policing,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 89(3):775-836, (1998-99): available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?artic… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Police Accountability Task Force, Recommendations for Reform: Restoring Trust between the Chicago Police and the Communities They Serve, 2016, 35.

- Andrea J. Ritchie and Brit Schulte, “Prostitution-Related” Loitering Ordinance Promotes Racial Profiling in Chicago, TruthOUT, July 24, 2018, available at: https://truthout.org/articles/anti-prostitution-ordinance-promotes-raci… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Elizabeth Bernstein, Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of Freedom, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018, 38-40; Liat Ben-Moshe and Erica R. Meiners, “Beyond Prisons, Mental Health Clinics: When Austerity Opens Cages, Where do The Services Go?,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- Fran Spielman, “Aldermen demand at least 500 — and as many as 1,000 — more cops,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 7, 2016, available at: https://chicago.suntimes.com/news/aldermen-demand-at-least-500-and-as-m… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Elizabeth Bernstein, Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of Freedom, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018, 38-40; Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); Teresa Gowan, “Thinking Neoliberalism, Gender, Justice,” Scholar & Feminist Online 11.1-11.2 (Fall 2012/Spring 2013); Liat Ben-Moshe and Erica R. Meiners, “Beyond Prisons, Mental Health Clinics: When Austerity Opens Cages, Where do The Services Go?,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Organized Abandonment and Organized Violence: Devolution and the Police,” lecture at the Humanities Institute at the University of California Santa Cruz, 11.9.15, available at: https://vimeo.com/146450686 (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Ryan Lugalia-Hollon and Daniel Cooper, The War on Neighborhoods: Policing, Prison and Punishment in a Divided City, Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2018; Michael Omi and Howard Winant, “How Colorblindness Co-Evolved With Free-Market Thinking,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014; Karen Gustafson, Cheating Welfare: Public Assistance and the Criminalization of Poverty, NYU Press, 2011.

- “E-carceration” is a term used to describe forms of electronic surveillance (i.e. ankle monitors) and incarceration (i.e. “house arrest”) offered as substitutes for incarceration in prisons and jails. See Challenging E-Carceration, “What is E-Carceration?” available at: https://www.challengingecarceration.org/what-is-e-carceration/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, March 4, 2015, available at: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachme… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Melissa Sanchez and Sandhya Kambhampati, “How does Chicago make $200 Million a Year on Parking Tickets? By Bankrupting Thousands of Drivers,” Mother Jones, February 27, 2018.

- Chicago is not Broke: Funding the City We Deserve, www.wearenotbroke.org.

- Melissa Sanchez and Sandhya Kambhampati, “How does Chicago make $200 Million a Year on Parking Tickets? By Bankrupting Thousands of Drivers,” Mother Jones, February 27, 2018; Institute for Race and Public Policy, A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report, 2017, 5 (“Black Chicagoans have the longest commute-to-work times in the city.”).

- Melissa Sanchez and Sandhya Kambhampati, “How does Chicago make $200 Million a Year on Parking Tickets? By Bankrupting Thousands of Drivers,” Mother Jones, February 27, 2018; Institute for Race and Public Policy, A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report, 2017, 5 (“Black Chicagoans have the longest commute-to-work times in the city.”).

- Melissa Sanchez and Sandhya Kambhampati, “How does Chicago make $200 Million a Year on Parking Tickets? By Bankrupting Thousands of Drivers,” Mother Jones, February 27, 2018; Institute for Race and Public Policy, A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report, 2017, 5 (“Black Chicagoans have the longest commute-to-work times in the city.”).

- Trymaine Lee, “Amid mass school closings, a slow death for some Chicago schools,” MSNBC.com, December 26, 2013, available at: http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/dont-call-it-school-choice (April 20, 2019); Liat Ben-Moshe and Erica R. Meiners, “Beyond Prisons, Mental Health Clinics: When Austerity Opens Cages, Where do The Services Go?,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/dont-call-it-school-choice

- Aaron Cynic, Backlash To Rahm Emanuel’s Education Record Impacts Chicago Mayor’s Race, Shadowproof.com, February 28, 2019, available at: https://shadowproof.com/2019/02/28/backlash-to-rahm-emanuels-education-… (last visited April 30, 2019); Aaron Cynic, “How Megaprojects Perpetuate Income Inequality Is A Major Issue For Next Chicago Mayor,” Shadowproof.com, January 14, 2019, available at: https://shadowproof.com/2019/01/14/how-megaprojects-perpetuate-income-i… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Liat Ben-Moshe and Erica R. Meiners, “Beyond Prisons, Mental Health Clinics: When Austerity Opens Cages, Where do The Services Go?,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- Liat Ben-Moshe and Erica R. Meiners, “Beyond Prisons, Mental Health Clinics: When Austerity Opens Cages, Where do The Services Go?,” The Public Eye, Fall 2014.

- “Social Movements Brought Down Rahm Emmanuel – Now They Can Transform Chicago,” In These Times, September 18, 2018, available at: http://inthesetimes.com/article/21426/rahm_emanuel_mariame_kaba_protest… (last visited September 18, 2018).

- Institute for Race and Public Policy, A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report, 2017, 1, 16, 21.

- Chicago Police Department CLEAR Map Crime Summary, http://gis.chicagopolice.org/clearmap_crime_sums/startpage.htm# (last visited April 30, 2019).

- The same information is not necessarily available for each of the neighborhoods listed.

- “Social Movements Brought Down Rahm Emmanuel – Now They Can Transform Chicago,” In These Times, September 18, 2018, available at: http://inthesetimes.com/article/21426/rahm_emanuel_mariame_kaba_protest… (last visited September 18, 2018).

- Grassroots Collaborative, #REIMAGINECHICAGO platform, <insert link when available>

- For more information about the #NoCopAcademy campaign, please visit www.nocopacademy.com.

- Benji Hart, How #NoCopAcademy Shook the Machine, Chicago Reader, April 26, 2019, available at: https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/how-nocopacademy-shook-the-machin… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- #NoCopAcademy: The Report, available at: https://nocopacademy.com/report/(last visited April 30, 2019).

- ‘Block the bunker’ activists vow to keep fighting stalled North Seattle police station, Seattle Times, September 16, 2016, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/block-the-bunker-bac… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- See https://nonewsfjail.wordpress.com/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- See https://lanomorejails.org/; http://justicelanow.org/jailplan/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- See https://www.closetheworkhouse.org/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- See https://mijente.net/expanding-sanctuary/; Mijente and BYP100, What Sanctuary Means is Something Different, Something For Everyone, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=syWPK0rwBc0 ( last visited April 30, 2019).

- See www.erasethedatabase.com.

- National Immigration Law Center, “AB 90: More Welcome Fixes to California’s Gang Database,” November 2017, available at: https://www.nilc.org/issues/immigration-enforcement/ab90-fixes-to-calif… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Key Points of the CSA, https://providencecommunitysafetyact.wordpress.com/about/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Alice Spieri, “NYPD Gang Database Can Turn Unsuspecting New Yorkers Into Instant Felons,” The Intercept, December 5, 2018, available at: https://theintercept.com/2018/12/05/nypd-gang-database/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- For more information, please visit Chicago Police Department Class Action Lawsuit, https://cpdclassaction.com/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- For more information about the Chicago Torture Justice Center, please visit: http://chicagotorturejustice.org/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- For more information on the Fight for $15, please visit: https://fightfor15.org/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Juan Perez, Jr., “Chicago Teachers Union suspends city’s second charter school strike after winning pay increases,” Chicago Tribune, February 18, 2019.

- John Byrne, Community groups to sue over Lincoln Yards tax subsidy, Chicago Tribune, April 16, 2019, available at:https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-met-lincoln-yards…; For more information on the Lincoln Yards Project, please watch https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=790309794682913 (last visited April 30, 2019).

- For more information, please visit: http://www.obamacba.org/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- SouthSide Together Organizing for Power (STOP!), Trauma Center Won! (For Real This Time), available at: http://www.stopchicago.org/2015/12/trauma-center-won-for-real-this-time… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- The Case for Reparations at the University of Chicago, Black Perspectives, May 22, 2017, available at: https://www.aaihs.org/a-case-for-reparations-at-the-university-of-chica… (April 30, 2019).

- Treat Gun Violence Like A Public Health Crisis, One Program Says, NPR, March 8, 2017, available at: https://www.npr.org/2017/03/08/519068305/treat-gun-violence-like-a-publ… (last visited April 30, 2019). For more information on MASK, please visit: http://ontheblock.org/ (last visited April 30, 2019).

- Debbie Bookchin, “The Future We Deserve,” ROAR Magazine , August 19, 2017, available at: https://truthout.org/articles/radical-municipalism-the-future-we-deserv… (last visited April 30, 2019).

- For more information on community-based transformative approaches to harm and violence, please visit: transform-harm.com, created by Mariame Kaba. (last visited April 30, 2019).