This article is based on a two-hour roundtable and has been edited for length and clarity. An excerpt of this article appeared in the Summer 2024 print edition of The Public Eye.

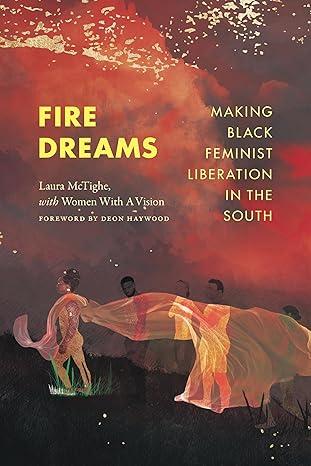

Fire Dreams: Making Black Feminist Liberation in the South (Duke University Press, 2024) tells the story of New Orleans-based Women With A Vision (WWAV) and the collective’s Black feminist liberatory praxis rooted in the U.S. South.

Since 1989, WWAV has organized with Black women, queer and trans communities of color, sex workers, drug users, and people living with HIV/AIDS against the criminalization of their communities. In 2012, on the heels of a major organizing victory, arsonists attacked WWAV’s office, destroying their longtime organizing home and physical records of their work. That could have stopped WWAV’s work—but it didn’t.

In the fire’s wake, WWAV decided to document the organization’s rebuilding. That led to Fire Dreams, a collaborative ethnography of WWAV that presents a living archive[1] of the group’s work and a toolkit for movement organizers.

As fires blaze across the U.S. and the world, what can movement builders learn from WWAV’s relational organizing for health and reproductive justice, and their practice of “research as survival”?

To find out, PRA spoke with WWAV’s executive director Deon Haywood; Fire Dreams coauthor Laura McTighe, an associate professor of religion at Florida State University and longtime WWAV accomplice; and Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson—then co-executive director of the Highlander Research and Education Center, which was firebombed in 2019—about surviving White supremacist and state violence.

PRA: Could you tell us about WWAV’s intersectional work and how this book came out of it? Why was it important to you to tell this story of making Black queer feminist-led liberation from the South?

Deon Haywood: I’m going to read something we wrote a week ago on my whiteboard to set the stage: “WWAV was founded at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis and the War on Drug Users. For 35 years, we have used the principles of harm reduction to care for our community. Today, it is no different. We are using tools like our Post-Roe Survival Guide[2] to ensure our community has the resources needed to survive regardless of lawmakers’ attacks.” I’m reading this as a reminder of where we come from and why we exist to this day.

The book came about because we were targeted. In 2012, I was getting multiple death threats on a weekly basis. I didn’t get that until we started looking at policy in post-Katrina Louisiana—how the criminal justice system was using our people as a pawn to get federal dollars, and making the connection to police violence, which we saw happening to so many sex workers, both cis and trans women. They experienced violence on an everyday basis and from police. Our lawmakers, with DOJ funding after Katrina, were saying, “We’re gonna catch all of these violent offenders.” They were targeting and picking on sex workers.

We spoke out and met with the DOJ to try to get a consent decree against the local police department here. We held community meetings with trans and cis women, and queer people who had experienced police violence. Sometimes it was standing room only.

Almost two months after we won the Crime Against Nature by Solicitation case [with a legal team who filed the case in partnership with WWAV, resulting in the removal of sex workers convicted under the law from a sex offender registry[3] – Ed.], we got a call about the arson attack at our office. We lost so much. Documents, WWAV’s history, our first bylaws, and unique, handwritten notes from our founding mothers [Catherine Haywood and Danita Muse]. The next day after the fire, our clients showed up to donate. They knew that people around the country were giving [and they wanted to help us rebuild]. That’s when we realized we were doing something special.

At the time, Laura was on the board. We decided we needed to capture this—to record the story of who we are and how we do this.

One of our community members said [that day], “We’re gonna rise like a phoenix.” Fire is destructive, but it can also be renewing. And in that moment, we decided that was just going to be how we captured and documented the work.

Laura McTighe: Everything WWAV does is rooted in relationships, which are the theory and method of change. Deon’s mom [Catherine Haywood], always says, “You have to build a relationship. When you have that, you can do anything. But if you don’t have that, you can’t do anything.”

Honestly, we weren’t trying to write a book. We were trying to ensure the next iteration of WWAV’s work. We’ve seen this with archives and libraries being destroyed as part of the genocide happening now in Gaza: When you want to destroy people’s future, you try to obliterate their past. That’s why WWAV’s space was attacked.

But we learned quickly that so much of what WWAV has done has been carried in relationships and in stories. Continuing to do this—sitting on the front porch, making harm reduction packets, talking to community—was the rebirth and renewal of WWAV’s work after the fire.

We knew we were living through something that most people didn’t survive, much less come out to be as strong, through Deon’s leadership and all the people who have carried this work forward. And that was a story we had to share. We were seeing fires like that multiply across our world, and people needed tools for how to get through this—not only intact, but with your principles guiding and opening a broader horizon for liberation.

Ash-Lee Henderson: Relationships are the capital that we’ve got in the absence of philanthropic dollars for the kind of lifesaving work that WWAV does.

It’s about survival. The work gets done because of those relationships. It shouldn’t be revolutionary, but it is. What makes relationships revolutionary is how WWAV develops relationships: interdependent, not codependent, relationship between a base-building organization that also does direct service and mutual aid and political education.

And I want to be clear: WWAV could sustain this work after the fire because of the way that Deon leads, how her mother did before her, and how she’s training her family to lead in organizing and her staff to be in organizing. There’s trust between residents of New Orleans and WWAV, because they do what they said they’d do and people respond in kind by saying, when you need something, we got you. But right now, there are not enough folks who are doing the work like Deon Haywood and WWAV.

PRA: In Fire Dreams, WWAV theorizes the “racial capitalism playbook” operating in our daily lives—and how Black women’s existence and organizing presents a counterplaybook that refuses this playbook’s logic. What lessons does the book offer to movement organizers and strategists for building the world otherwise in the face of unrelenting systemic violence and the resurgent Right?

Laura McTighe: When Andrea Ritchie did a book talk for Practicing New Worlds, she talked about the long view of her organizing work and how she realized that if she wasn’t in her own imagination, she was going to be in someone else’s.[4]That’s why it matters to us to name how racial capitalism is working in our everyday lives, to call those steps “a playbook,” because that is how the folks who are trying to destroy us work, and what WWAV does—through front porch strategy and our tools—is an entirely different process of worldbuilding.

We distilled the racial capitalism playbook’s steps in the wake of the arson attack to make sense of and name what WWAV’s foremothers and people before them have been living. Racial capitalism works by isolating people from necessary services, blaming them for the strategies they use to survive, criminalizing them for their survival, destabilizing their communities, erasing people from space, and taking their land.

That last part about space is critical. Space is the foundation that makes everything WWAV does possible: the space of front porches, the space of harm reduction outreach, and the spaces we make and defend in the face of the violence of racial capitalism.

In the book, we also theorize how WWAV works in space, and we offer several tools that have been honed through generations for making liberation.

The first tool goes back to what we were saying about relationships: We center accompliceship. WWAV’s foremothers worked as accomplices with drug users, sex workers, people who had nothing, and asked, “How can we support you in thriving?” Accompliceship is also central to how we think about the relationship that Deon and I have, and what it means to be for me to be working as a White queer abolitionist in service of Black women’s leadership.

The second tool is refusal, which is exactly what it sounds like. Deon can tell stories about our foremothers saying “We’re not doing that. We’re not going to play nice with systems that hurt our people.” That’s essential to why WWAV has been able to win things that no one else thought were [possible]. It’s also a fundamental piece of abolitionist organizing: [Refusal means that] you don’t separate “good” and “bad” people or make perfect “victims.” You move with people through their lived experience, unapologetically, and refuse anything that asks you to compromise that.

The third tool is otherwise—to not only imagine a world that could be, but to recognize that this world already exists around us every day in the possibilities and the joy that WWAV makes together in community. We try to connect those otherwise possibilities, to grow and strengthen them.

The last [tool in the book] is speech, which we center because of Deon’s leadership and the power of her voice. Speech attunes us to the importance of storytelling as another theory and method for us, and also to what it means to speak something into being—recognizing that there are certain words we will [not] put in our mouths, because words have power, and we will not continue to create worlds that are not about living and thriving.

[These tools] aren’t cookie cutter molds, but if you move all the pieces in formation, they build something different.

Deon Haywood: About the refusal part: It was modeled for me. Most leaders don’t know that you have the power to refuse. In the book we talk about my mom and Danita giving money back to people.

I knew it was okay to refuse and that I was still going to win. Everybody thinks you need money to win, but every single revolutionary moment that has happened in this country took place without money.

[An example of] when we win is having the first ever diversion program for sex workers operated from our office, not the court. Sex workers would not be rearrested within five to seven years, as long as they’re connected to us. That may not be a win to somebody, but guess what? Sex workers can be at home, with their kids, and live and work through stuff with our support. That’s winning and building revolutionary partners. The people most affected become the people who are fighting. They’re nobody’s victims. They’re the winners in it all.

Ash-Lee Henderson: Deon’s description of [refusal] is the answer to the question. For me, this book isn’t a counter to the right-wing agenda to impact folks with HIV/AIDS or some innovative new strategy. For the last 35 years, WWAV has been a proof of concept of what Black women have been doing for centuries to dispel what the right-wing White supremacist patriarchy has been trying to prove in response to the beloved community that we’ve been building.

Fire Dreams is not the counter play. It’s the play. The Right is doing the counter. This arson was an attempt to break the long-term win. They didn’t. Why would they have risked an arson charge if Women With A Vision was losing? Just think about it, right? If this little 30-year-old organization was doing nothing but getting rid of a 200-year-old law that didn’t really matter, then who cares what they’re doing?

WWAV was building a multitactical strategy with a multisectoral base. They were doing direct services, public health, and reproductive justice, and organizing a working-class, multiracial base in the belly of the Southern beast, amid converging and escalating crises and blowbacks.

WWAV’s prefigurative vision for New Orleans and the world is what we desire for our homes across the South and the country: how people would be treated, what relationship would look like, what mutual aid and community care could look like in states where the Democrats and Republicans alike have abandoned us. They modeled an understanding that if you build a strategy that is grounded in principles and values, you can bend time to make the prefigurative possible.

WWAV does this by building power for people to be able to change the material conditions of their communities. What might have felt to some like micro interventions in this multitactical, long-term strategy, is what helps us truly actualize more of those abolitionist fire dreams.

The Right has a strategy and the infrastructure to execute that strategy, but it’s in response to what we’re doing. We can be on the back foot and react to them, or we can stay focused on meeting people’s immediate needs—or harm reduction with short-term interventions—while keeping our eyes on the prize of where we’re going. Our role towards getting there is something our movements can learn from this book.

PRA: Ash-Lee, when you were talking about the book yesterday ahead of this conversation, you referred to it as a blueprint. Maybe that gets at its prefigurative vision?

Ash-Lee Henderson: It’s the blueprint for how to win things. One thing that I love about the book is it’s about what you should be doing before, during, and after the intervention. And while you’re doing all those things, be prepared for the blowback that comes. If you are and on mission, you can build momentum, regardless of what’s going on with the Right. While they’re doing fearmongering, we’re over here, saving lives. Y’all can get on board or not, but we’re going to this vision. We’re doing that.

So, I don’t think it’s counter to anything. I think it’s something that the Right is responding to—and has been for centuries.

This book is a trust that has a few decades of our history written on the page, while also instructing us on interventions we could make in a 21st-century context to build our power and ourselves in a way that is full of love and joy and resplendentness, while grieving our dead and protecting our living.

PRA: WWAV and Highlander both serve communities that have survived ongoing structural violence and White supremacist terror. Your organizations survived arson attacks that could have stopped your work, but they didn’t. What kept you all going and how is your vision for another world enacted in the work you did after the fires?

Ash-Lee Henderson: Deon and Laura have spoken about how WWAV’s experience is that they weren’t the first, last, or only group to get attacked. When Highlander was attacked, it wasn’t even the first time we had been firebombed. It was my first time, but it wasn’t our organization’s or our intersecting movements’ first time being under attack, even in that month. Black churches were being bombed by White supremacists all over the South during that time. Mosques and synagogues across the country were under attack. And in fact, [a few weeks after] the Highlander arson, the holy mosque in old city Jerusalem had been set on fire.

We were screaming canaries in the coal mine—we knew this movement was growing and they had tried to make a play for U.S. governance before. And we also saw global connections: the very symbol that they spraypainted in [Highlander’s] parking lot the morning of the arson was etched into the nozzle of the gun of the mass shooter in Christchurch, New Zealand.

We were telling people not to be shocked in 2024—it’s been a crisis and we’ve been saying this for a very long time. If folks would not only wear T-shirts that say, “Trust Black women,” but actually follow our leadership, it probably wouldn’t get this bad.

Second, I don’t want to dismiss the courage that it takes to keep working. But I also want to be clear: The mission is the mission is the mission. If the work isn’t done, it ain’t done.

[On the day of the arson] our people were going to the Hill for that weekend’s Appalachian People’s Movement Assembly. I said, “Y’all, we can turn people back,” because we didn’t know if [the arsonists] were coming back. They marched on Planned Parenthood Knoxville, which they went on to bomb, and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Our staff said, no, let’s do this. So, we did. When the threat was too high to manage, we wrapped up the work. We sent folks home before nightfall, and I decided to stay and wait. To stop doing the work would have given them a win that I just wasn’t willing to do.

Third, we had to do the work, but we also had to take care of people so they could do the work. There was no “get out of grieving” card. That sacred land, and the animals and beings on it were also impacted. We took that as seriously as our individual and collective self-care. I think we had to be intentional about making sure our spirits were mended enough to continue the work.

Fourth, we had to be intentional about not being the arsonists’ evangelists. We didn’t want them using this as a recruitment tool.

Finally, [Highlander’s co-executive director] Allyn and I knew we weren’t alone and didn’t have to be. It meant something that Deon called and that the co-executive directors of Project South drove up that morning. We had a community of people who had been through this before or were willing to learn how to go through it with us. To prioritize keeping each other safe, well, ready, and in this work, despite attacks from the Right. I don’t know that we would have known how without that comradeship.

Deon Haywood: The White supremacist playbook tells us to prove that we are good and kind, taking away our power to own the truths of our history in this country. What made us keep going is that we didn’t have that mindset.

The police didn’t investigate. People were surprised that we didn’t push back, but I don’t want their investigation. We know who did it.[v] The police know. They chose not to do anything. And WWAV continues to be attacked in so many ways, in this abortion ban moment.

We push forward. I lean on ancestors biologically connected and those connected through movement. Harriet ain’t stopped. Ida didn’t stop writing and witnessing and telling the story. What would it look like for me, for who I am, to say, “Well, I guess we’re gonna close our door.” No, the door will stay open, and we’ll continue to move. Let’s continue to do this work.

I am here for a purpose. And some of us are called. For those of us who are called, there is no shutting down.

We have to realize that White supremacy is still destroying us. It’s why we don’t have the funding we deserve. Funders are even having conversations about whether they should stay in the South. That’s White supremacy, because they can make the choice to leave. Those of us in it, there is no choice to leave. There’s the fire—or, the conditions we’re living in right now. For where we’re going, there must be a knowledge of history. The Civil Rights Movement was a beautiful playbook. There was synergy among Black people. Even when there was a fire or people were attacked, they continued to move.

Ash-Lee Henderson: When Highlander was under attack in the late ‘50s, it was another convergence of crises: White supremacy, Jim Crow, the Red Scare. Anti-Black and anti-Communist sentiment combined in a multitiered attack against Highlander for bringing Black and White people together with a class consciousness. Miss Septima Clark was running a youth program that got raided. They arrested people, including Miss Clark, and it became clear they were going to do everything in their power to shut us down, including a court case.[6]

To Laura’s point earlier, our network of relationships puts us in a position of being able to continue the work—sometimes, despite what other people in movements advise. Black women’s lived experiences, connectivity to our ancestral legacies and the strategies implemented by our elders, and access to limited resources are what kept us safe.

The lessons still come to this day out of what we did in the face of the 2019 arson. It’s also different from what others experienced because there is an ongoing federal investigation. Frankly, we weren’t considered the attack’s victim until very recently. So, Deon and I also have lessons about how to navigate being accused of the attack that was against you. We have questions about how to navigate the state in all of its layers. I don’t want to dismiss the importance of that, but what Deon said made me think of something that’s more important now: what it means to have to say yes to continuing that’s rooted in being dedicated to staying, fighting, and winning in a place as this fascistic authoritarian movement to take over the federal government is happening.

Deon Haywood: The fight will become different. It’s already different. And so there must be a plan in place. Without naming it outright, that’s what Fire Dreams names. We need a game plan because everybody can’t leave. And the reality is that to leave [the U.S.] is leaving for another form of White supremacy.

Ash-Lee Henderson: If we had let arson stop us from doing the work to fulfill our mission, then the Right had already won. We were both committed to not allowing that—not for the sake of being petty, but for the sake of building power for the bases that we’re accountable to.

PRA: What have you learned from each other’s responses to these attacks?

Deon Haywood: I was deeply inspired by and in love with Ash in that moment. As horrible as that moment was, it also felt good because Ash showed great love in that moment.

That moment for Highlander was, yes, hard. But I felt like, “Oh, they got this,” because I had been there and knew that everybody involved could do what was needed. When we went to Highlander at that time and saw security go around the truck, it reminded me of how people were looking out for WWAV. It was a reminder that all of this is so much bigger than we think. It’s so much bigger than some of us can hold. It’s the anger, the love, the confrontations, the growth. Something about that fire made us stronger. In that way, the answer to the people behind these attacks is: you did nothing. All you did was fuel our need to do the work we’re doing.

Laura McTighe: Arsonists attacked WWAV because we were winning—and it’s the same with Highlander’s continuing legacy. We’re also seeing the same thing in this political moment. Fascists are literally grabbing at straws, trying to stop the new world we are building from coming into being.

In the fire’s wake, WWAV had to interrupt the notion that the arson was a singular attack on one organization at a single moment in time. And we learned so much by doing that—by talking to and caring for one another and connecting to this land’s histories of struggle. It bent time and put us in touch with every other moment [when something like this had happened].

When people resort to that level of violent tactic against us, it means that we’re already on the road to doing something that’s gonna transform the world as we know it. And there is no stopping us, because we are moving with the strength of generations.

Ash-Lee Henderson: We learned so many things from WWAV—in relationship to the arson and otherwise. They are the blueprint.

By withstanding White supremacist, patriarchal, and state-sanctioned violence against their work, WWAV and Deon taught me that anything can be a platform to amplify the lifesaving work people are doing. Seeing that, I understood that I could decide to communicate about the enemy and what they did to us, or I could focus on how we have another option rooted in vision—one that’s not taking us back, like the right-wing playbook [is].

WWAV and Deon also taught me that it’s an opportunity to model what leadership should be like. It should be empathetic.

It wasn’t just about Highlander or WWAV. White supremacists wanted to destroy our infrastructure. Which is why it was important to talk about all of us when we had access to platforms. It’s an opportunity to continue to ring the alarm about the rise of the White supremacist, Christian nationalist, fascistic authoritarian movement in this country at a time when people were still saying that fascism is impossible in the U.S.

Despite being attacked multiple times, WWAV has been able to address the primary contradiction [of fascism’s ascent] in the moment while moving towards their vision. All of us should be as disciplined and rigorous. We were able to [follow their example] during the arson, so I’m convinced that they have proved the concept. And if we do that now, we might salvage even the performance of democracy in this country, which makes everything else, including reproductive justice, more possible.

PRA: What do you hope readers will take away from this approach to working with fire that you’ve written about so beautifully in the book, and how they can use it?

Deon Haywood: I hope people see themselves in the book, are inspired, and become our thought partner. It’d be nice if somebody reads the book and wants to be in conversation or create deeper relationships with people who we may not be in relationship with.

How can you engage? Find your organizing home, find your people. That could look different [than our groups], but we’re all engaged so that when the time comes, we know we gotta move. I just want people to be inspired and to know that the other world, the otherwise, is possible.

Laura McTighe: We come back throughout the book to doing the work and what that means. This book is an invitation to do exactly what Deon just shared.

What is so important about WWAV’s work is how it models building intergenerational struggle. The racial capitalism playbook tries, through mass incarceration and the destabilization of communities, to sever intergenerational movement relationships. This book offers a history of how we got here. It’s a literal “pull up a seat on the front porch” modeling of what it looks like to be moving through four generations. Through pictures, and naming and calling people, the book shows how this is possible. I think about the power of that for younger organizers who were severed from intergenerational movement, and our elders who are not getting their flowers—what it means to honor them.

This book holds so much love, and that invitation to love is important.

Also, because White supremacy and the fact that White people cannot follow Black leadership is destroying our movements, there’s something about our relationship that Deon and I also want to offer: about what it meant to be bringing our voices together in a collective “we,” where the center and force of the “we” is always Black women’s leadership. That is a central piece I want folks, especially White folks, to take away.

Ash-Lee Henderson: I hope this book inspires movement practitioners. I hope it reinvigorates the desire to be in deep study for the sake of experimentation that changes the material conditions of our people. That we can apply the lessons, but work [on] what didn’t [work], and repeat—in sum, practice. Don’t just read the book and then, to Laura’s point, not do the work.

I also hope people get out of this book that the form of your tactic should follow the function of your strategy, which should be building power for our people. That’s the metric, right? Did it build power for our people? If it didn’t, you’re not doing the work. And last but not least, I hope people recognize Deon’s leadership in this time and how important WWAV has been to the Southern freedom, Black liberation, and Black queer feminist movements. I’m glad that it is forever codified in the book’s pages.

Laura McTighe: We also want to extend an open invitation to be a part of this. We’re not doing a typical book tour because Fire Dreams is not just a book to be read; it’s a toolkit for building the world that must be. We’re partnering with organizers across the country and using this tour to connect with, support, and learn from their organizations. For anyone who is reading this: If you are working on a project—in-person or virtual—that is doing the work to build and grow the movement that will free us all, we want to support you. [This tour] will invest in everyone who reads this book to help you translate our tools into ones that you can use to build otherwise in your corner of the world.

Endnotes

- Women with a Vision, Born in Flames Living Archive, https://www.borninflames.com/, for more about the “living archive” from which the book emerged.

- Women with a Vision, Your Survival Guide to a Post-Roe Louisiana, November 2022, https://wwav-no.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Post-Roe-PDF.pdf.

- Center for Constitutional Rights, “Crimes Against Nature by Solicitation (CANS) Litigation,” accessed September 30, 2024, https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/crimes-against-nature-solicitation-cans-litigation.

- Andrea Ritchie presents Practicing New Worlds, Red Emma’s, Baltimore, MD, October 28, 2023, event attended by speaker.

- Haywood notes here that “Neighbors said there was a White male running from the scene.”

- The state of Tennessee revoked the Highlander Folk School’s charter in 1961 and seized its land and buildings, following years of government investigation and red-baiting. The school reopened the next day with its current name. Refer to Highlander Research and Education Center, “90 Years of Fighting for Justice,” accessed September 24, 2025, https://highlandercenter.org/our-history-timeline/.