This article is excerpted from The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics in a Burning World (London: Repeater Books, 2024), 11–15 and 33–36, and is reprinted with permission from the publisher. An earlier version appeared in The Baffler. The excerpt has been significantly edited for brevity and style.

One of the most common misconceptions concerning climate change is that it produces or even requires a united humanity. In that tale, the crisis in the abstract is a “common enemy,” and a perfectly universal subject is finally possible in coming to “experience” ourselves “as a geological agent,” through which a universal “we” is constituted in a “shared sense of catastrophe.”[1]

The story I am telling you is different. In this story, there is no universal “we.” Although there are so many stark political divides imaginable, the political divide of this moment is almost

the quintessential, perfectly political divide. It is literally zero-sum. The divide is not, as many still argue, between those who accept and those who reject the overwhelming evidence of climate science.[2] It is about those who stand to gain—both in this moment and in the future as traditionally conceived—from fundamental system preservation or other modes of right-wing climate realism, and those whose current exhaustion is part of the fuel for that system as much as any petrochemical or industrial agricultural process. Climate change is not the apocalypse, and it does not fall on all equally or, in at least a few senses, on everyone at all.

Right-Wing Climate Realism

The idea of right-wing climate realism can strike many as odd in the first instance. Since, the assumption runs, climate change is universal, since we can turn to a “scientistic” politics, there is only one “climate realism,” and the primary task is to communicate, persuade, and teach the science from which the one-true-politick will emerge. All that stands in the way of this is the intransigence of non-believers. This is, perhaps ironically, a familiar story: it is a Christian story of gospel and evangelism. But the science does not have a single politics. Right-wing climate realism encompasses a plausible and thoroughly realistic—in terms of power and in terms of ecology—set of positions in which a business-as-usual scenario is absolutely worth it. Even given the staggering social and ecological costs, it might even be salutary, and not in some short-term or self-deluded sense. Right-wing climate realism then, in its simplest form, is a political-ecological scenario of the concentration, preservation, and enhancement of existing political and economic power.

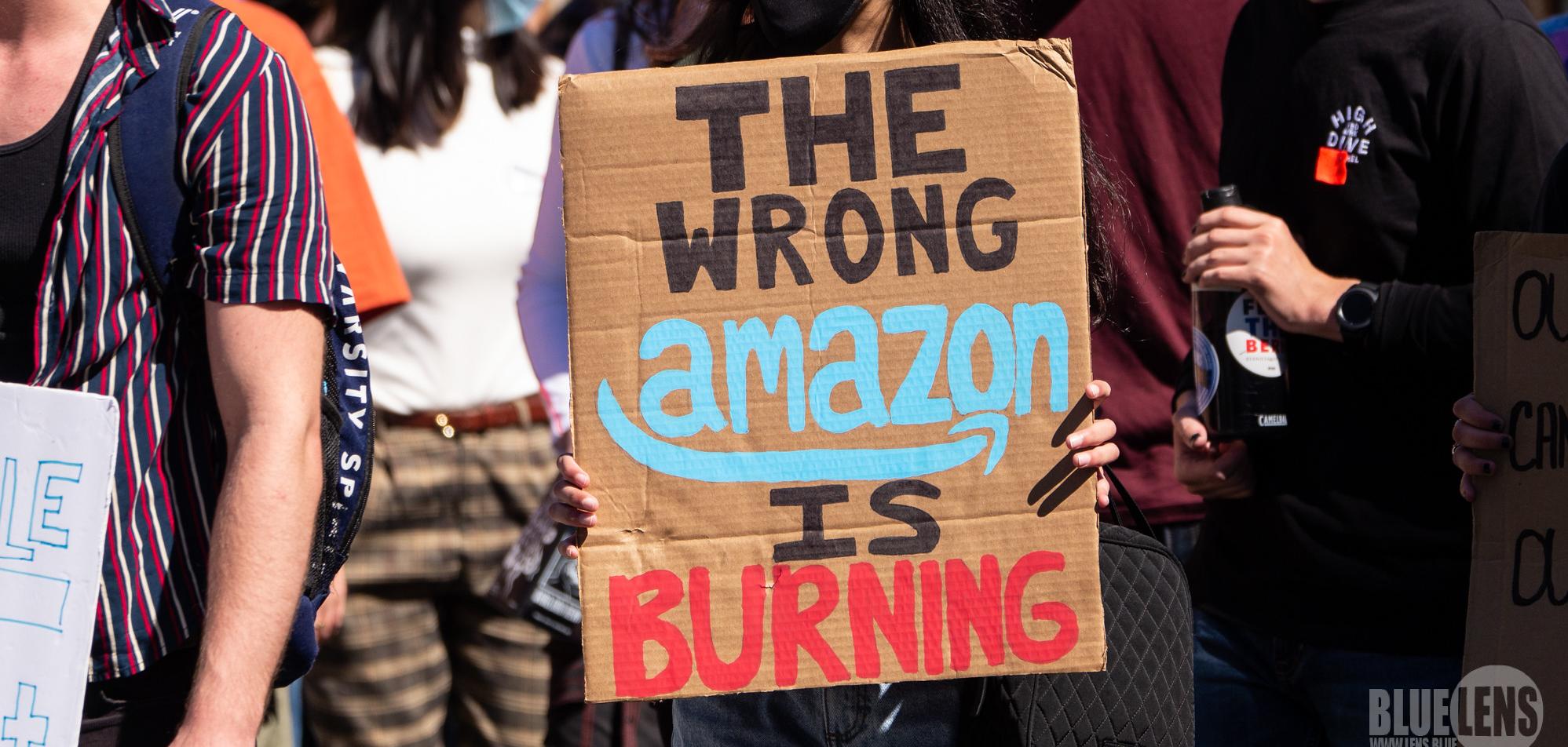

Although the threat of ecologically articulated right-wing politics is quite real, has historical antecedents, and is visibly present in fringe and radical right movements in this moment, much of what might be better understood as right-wing climate realism need not be articulated as ecological at all.[3] It can simply build from what the right has already formidably established and wishes to pursue further. This is not something we see only in the Pinkertons and other private security agencies investing in climate-related protection for the wealthy,[4] but something we can observe in tax policies that go far beyond neoliberal catechism, maximizing accumulation while disincentivizing investment of any kind. It’s not only a world in which what the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calls “phantom FDI”—foreign direct investment which goes towards no discernable actual investment but is rather just convenient avoidance of taxation and popular sovereign restriction—has shot up to 31 percent of all FDI.[5] It’s a world in which even that cannot fully explain the 40 percent of “missing profits” that are simply unaccounted for.[6] It’s not only the U.S. military preparing for climate security scenarios and buildouts, it’s the U.S.’s continued investment in the world’s largest existing migrant detention, surveillance, and expulsion network. It’s not only the development of what I call “detachable infrastructures”—luxury survival architecture built not only with internal power generation and potential for stockpiles, but to receive aerial deliveries and withstand floods or riots.[7] It’s Amazon’s infamous patented “airborne fulfillment center” which could connect far-flung supply chains with end-use consumption by drone delivery, furthering the development of ever-diverging narrow, luxury markets. […] This is not quite what people usually have in mind by “climate barbarism.”

[…] But, understood within a larger climate portrait, this is building or at least preparing for a world that is an extension of what I call the “extractive circuit”—that is, capitalism in the twenty-first century in its full socioecological expression,[8] working for fewer and fewer. Or one of vigilant, restrictive, hyper-nationalisms. Or even structurally “neofeudal,” a rather different “post-capitalist” vision for if or when the extractive circuit breaks. Or a world of all three. A world we can already see coming into its own in Fortress Europe or at the U.S. border and in increasingly direct and punitive anti-popular governance in places like Puerto Rico or Greece, Flint, or East Palestine. We can observe interstitial border states, like Turkey and Mexico, adopting the control of migrants as a geopolitical lever, but for a permanent “tier” below, providing a key service for the preservation of power in a world already experiencing migration on a scale not seen since World War II and projected to be in the hundreds of millions in the near term.

There is tremendous evidence that people deeply invested in fundamental system preservation do consciously proceed with “business-as-usual,” knowing with a reasonable degree of certainty the likely climate outcomes.[9] I often jokingly call this the “Rex Position,” named for Rex Tillerson, CEO of ExxonMobil from 2006–2016, and Secretary of State under Donald Trump for parts of 2017–2018. Tillerson famously proclaimed, “my philosophy is to make money. If I can drill and make money then that’s what I want to do.” Tillerson is not a climate denier per se. He just doesn’t share the urgency of his many critics. Tillerson is more than willing to talk about a shift to renewables, but there’s no rush. People will adapt to climate change, there are “engineering” solutions. It’s only those trapped within a different temporality who think otherwise. There are many clear and bright futures for business-as-usual in the meantime. There’s a certain clarity and precision in even Tillerson’s public arguments: “Our view reflects the reality that abundant energy enables modern life.”[10] The Rex Position is not one single positive political ideology but the convergence point of the politics of right-now for a panoply of right-wing climate realisms.

[…]

Whose Apocalypse When?

The argument is that whatever protections wealth and power afford will evaporate at some degree of a ΔX scenario. Of course, there is some X at which universal effects to such an extent really do begin. But that is not what we are talking about.

Some business-as-usual scenarios put the Earth on track for a Δ3–4°C change by the end of the twenty-first century, Δ5 accounting for the possibility that feedbacks might trigger a faster rate of warming or lock in a particular pathway. Somewhere around Δ4 seems likely with current business-as-usual.[11]

Add the already complex ecological picture to social systems—war, resource distribution, land-use—and it is even more difficult. A Δ4 or Δ5 scenario by 2100 is almost certainly characterized by mass deaths (direct and indirect), rampant disease in some regions, billions in food and water insecurity, vast numbers of climate refugees, resource conflict, and so on. But this is not “existential” in the mundane sense of the word; it is not extinction. As a recent study focusing on worst-case scenarios put it, “existential risk […] is not a solid foundation for a scientific inquiry.”[12] The authors instead focus on 10–25 percent mortality and fundamental institutional collapse—a world perfectly in line with the more neofeudal modes of right-wing climate realism. This is absolutely catastrophic—in no uncertain terms, that’s in fact the point of the research: “exploring severe risks and higher-temperature scenarios could cement a recommitment to the 1.5 °C to 2 °C guardrail.” But it’s not the perfect universal eschatology that informs so much thinking around climate change. Or, as Kate Marvel remarks, “it’s worth pointing out there is no scientific support for inevitable doom […] there is a real continuum of futures, a continuum of possibilities.”[13] Politically speaking, those possibilities have different weights, different logics, different existing or potential powers.

Climate change is not the apocalypse. Rather, coming to know right-wing climate realism and its worst possibilities is coming to know an enemy. To have a “clear-sighted” view of its concrete realities, its politics, and its passions, allows for the possibility that we might cultivate and externalize our own. This possible reactionary climate realism scenario is hardly certain. It could take differing forms across differing geographies. In some places we might see neofeudal company towns, but in others virulently and exclusive nationalist states; in some places massive “sacrifice zones,” as already exist around key points for the global extraction of rare earth metals or fracking; and in others, a rump state working in concert with private powers.

We can have Narendra Modi’s neo-fascist Hindutva “spiritual environmentalism”—which simultaneously dismantles India’s regulatory regime (99.82 percent of recent industrial projects have been swiftly permitted), boasts of its Paris commitments, pledges photovoltaic buildout, and preaches “special attention to yoga amidst discussions about climate change,” while pinning social and ecological crises on Muslims, Dalits, and “secularists” and pursuing adaptation and mitigation in ways that sometimes (literally) pave over them.[14] Or we can have Jair Bolsonaro calling for extractive genocide in the Amazon without much reference to ecology at all. We can have the burgeoning Green-Black ecofascist political formations coming back into European vogue that cite climate change as the reason for reactionary policies, from borders to eugenics. From the right-wing People’s Party of Austria (ÖVP) entering into a governing alliance with Austria’s Green Party and the French National Rally, with its own explicit fascist roots, saying that “borders are the environment’s greatest ally; it is through them that we will save the planet” to the Swiss People’s Party arguing “if you want to effectively protect the environment in Switzerland, you must fight mass immigration”—Green really is the new Black.[15]

It can be difficult to tell the difference between an ecofascist manifesto from a mass shooter, lamenting that the only politically “realistic” response to climate change is nationalist population control, and a “liberal” New York Times columnist commenting that “we have a real immigration crisis […] the solution is a high wall with a big gate—but a smart gate,” to allow in “desirable” people fleeing from economic, social, and ecological crises elsewhere.[16] But how different is this than the EU placing its notorious Frontex border control agency—which reiterates the new threats of climate migration — under the auspices of a commissioner to “protect our European Way of Life”? Or Dianne Feinstein saying it all just costs too much?

All of these are variations on a theme of right-wing climate realism—a cornucopia of Rex Positions generating similar visions of the preservation of power and security for a select few whose primary difference is intensity and audience. […]

The point is that, in some form, right-wing climate realism is not only plausible and possible, but probable. Such a world need not be characterized by some cataclysmic break with this one, nor would it be unrecognizable. Indeed, part of what makes this such a plausible outcome is that it is another intensification of the existing world.

Endnotes

[1] Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2 (2009), 197–222, here 220–222. Discussions about climate change as “apocalyptic” or human extinction are addressed elsewhere in the book.

[2] Data and analysis on climate denial can be found in the “Really Unreal?” section of the book.

[3] In his short article, “Survival of the Richest,” Douglas Rushkoff describes his experiences at a remote, exclusive mini-retreat for the ultrawealthy. During this retreat, at one point he is taken to an even smaller gathering in which issues such as how to pay private security in an economy in which resources have more value than money, or how to effectively prepare for mass rioting, migration, etc. resulting from climate and related crises, came up directly. I discuss both direct and indirect forms of right-wing climate realism in this book chapter.

[4] Noah Gallagher Shannon, “Climate Chaos is Coming — and the Pinkertons are Ready,” New York Times Magazine, April 10, 2019; refer also to Samuel Bowles and Arjun Jayadev, “Guard Labor: An Essay in Honor of Pranab Bardhan,” UMass Amherst Economics Department Working Paper Series (2004).

[5] The team led by the late atmospheric chemist Will Steffen (on the scientific basis for understanding the Anthropocene in general and the accelerating pace of climate change in particular), observe a direct correlation between FDI (among many other indicators) and anthropogenic climate change which establishes that “it is now impossible to view one [the socioeconomic] as separate from the other [anthropogenic climate change]. The Great Acceleration trends provide a dynamic view of the emergent, planetary-scale coupling, via globalisation, between the socio-economic system and the biophysical Earth System.” Steffen et al., “The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration,” The Anthropocene Review 2, no. 1 (2015), 1–18.

[6] On “missing profits,” see Thomas Tørsløv, Gabriel Zucman, and Ludvig Wier, “The Missing Profits of Nations,” NBER Working Paper no. 24701 (June 2018); on tax havens, see Gabriel Zucman, et al., The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens, (University of Chicago Press, 2015), 4–24. A team led by the Argentinian ecologist Sandra Díaz finds, among a general account directly linking “[t]he increase in the global production of consumer goods and the decline in almost all other contributions” to human ecological well-being, that “funds channeled through tax havens support most illegal, unreported, and unregulated” activity in areas like fishing, for example. Díaz et al., “Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change,” Science 366, no. 6471 (2019). Such activity is actually a widespread and cited feature of contemporary global capitalism, as discussed later in the book.

[7] On luxury survival architecture, see, for example, Proven Partners, “Resilient Design — The Newest Luxury in Real Estate?”; Icon Architecture, “Tempo: Cambridge, MA,”; Matt Shaw, “This Luxury Tower Has Everything: Pools. A Juice Bar. And Flood Resilience,” New York Times, April 29, 2020; and, for more extreme examples, Evan Osnos, “Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich,” The New Yorker, January 22, 2017, and Bradley Garrett, “Doomsday preppers and the architecture of dread,” Geoforum 127 (2021), 401–411. In a recent study, the Egyptian architects Bassent Adly and Tamir el-Khoury explore exclusive adaptation within “gated communities and enclosed neighbourhoods, gated enclaves, and private cities.” Palatial villas are retrofitted for energy efficiency—from insulation and orientation to private photovoltaic power supply (and private security).

[8] C.f. Ajay Singh Chaudhary, “Sustaining What? Capitalism, Socialism, and Climate Change,” in Philosophy and Politics—Critical Explorations (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022); Chaudhary, “Emancipation, Domination, and Critical Theory in the Anthropocene,” in Domination and Emancipation: Remaking Critique, ed. Daniel Benson (Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield, 2021); Chaudhary, “Toward a Critical ‘State Theory’ for the Twenty-First Century,” in The Future of the State: Philosophy and Politics, ed. Artemy Magun (Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield, 2020); Chaudhary, “It’s Already Here,” n+1, October 10, 2018, https:// nplusonemag.com/online-only/online-only/its-already-here/; Chaudhary, “The Climate of Socialism,” Socialist Forum, Winter 2019, https://socialistforum.dsausa.org/issues/winter-2019/the-climate-of-soc…; Chaudhary, “Subjectivity, Affect, and Exhaustion: The Political Theology of the Anthropocene,” Political Theology, February 25, 2019, https://politicaltheology.com/subjectivity-affect-and-exhaustion/.

[9] See Christopher Wright and Daniel Nyberg, Climate Change, Capitalism, and Corporations (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015), for a wonderful account of how “business-as-usual” discourse proceeds internally within firms. There we also see, alongside knowledgeable action, the choice not to know; see also Geoffrey Supran, Stefan Rahmstorf, and Naomi Oreskes, “Assessing ExxonMobil’s Global Warming Projections,” Science 379, no. 6628 (January 13, 2023) for a full account of, even with available records, just how clear climate outcomes were within firms like Exxon as far back as 1977.

[10] On the lack of urgency to shift to renewables, see Jesse Baron, “How Big Business Is Hedging Against the Apocalypse,” New York Times Magazine, April 11, 2019. Tillerson quotes are taken from Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital (New York: Verso, 2016) and Baron’s reporting.

[11] Luke Kemp et al., “Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios,” PNAS 199, no. 34 (2022); Steffen et al., 2018.

[12] On “existential risk,” see Kemp et al., “Climate Endgame.”

[13] For Kate Marvel’s remarks, see John Schwartz, “Will We Survive Climate Change?” New York Times, November 19, 2018.

[14] See Sam Moore and Alex Roberts, The Rise of EcoFascism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2022); Mukul Sharma, Green and Saffron (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2011); Anwesh Dutta and Kenneth Bo Nielson “Autocratic environmental governance in India,” in Routledge Handbook of Autocratization in South Asia (Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2021); almost all studies—academic and journalistic—treat such politics as deception or hypocrisy, which is fundamentally an error.

[15] On Austria, see Benjamin Opratko, “Austria’s Green Party will pay a high price for its dangerous alliance with the right,” The Guardian, January 9, 2020, and Oliver Noyen, “Secret deals with conservatives expose Austrian Greens,” Euraktiv, February 1, 2022. On France, see Aude Mazoue, “Le Pen’s National Rally goes green in bid for European election votes,” France24, April 20, 2019. On Switzerland, see Joe Turner and Dan Bailey, “‘Ecobordering’: casting immigration control as environmental protection,” Environmental Politics 31, no. 1 (2022), 110–131.

[16] Refer, for example, to “Full Text of Alleged Manifesto of El Paso Shooter,” https://web.archive.org/web/20190826155659/https://heartiste.org/2018/0…; Thomas L. Friedman, “Trump Is Wasting Our Immigration Crisis,” New York Times, April 23, 2019.