The Prochoice Religious Community May Be the Future of Reproductive Rights, Access, and Justice

“No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house.”

Matthew 5:15 NRSV

There is a vast prochoice religious community in the United States that could provide the moral, cultural, and political clout to reverse current antiabortion policy trends in the United States. Most, but not all, of this demographic are Christians and Jews. There are also deeply considered, theologically acceptable, prochoice positions and, therefore, prochoice people and institutions within all of major world religious traditions present in the United States, including Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Chinese traditions.1 Taken together, they have vast resources, institutional capacity, historic and central roles in many towns and cities, and cadres of well-educated leaders at every level—from national denominational offices to local congregational leaders, current and retired.

This cohort is often measured by reputable pollsters and may actually comprise the majority or near majority of the religious community. Nevertheless, it is not well identified or sought out by the organized prochoice community, the media, and elected officials. What’s more, this wide and diverse constituency is insufficiently organized by the prochoice religious community itself. But it could be.

This essay will show that this demographic, and the institutions and traditions that inform it, may be the best hope for restoring and sustaining abortion rights, access, and justice in the United States at a time when the Christian Right and its allies in state and federal government are undermining and seeking to eliminate them.

The Christian Right is indeed a well-organized minority that has achieved the heights of political power in the United States, but it could be dethroned. There may be a variety of ways to do this, but it stands to reason that any way forward ought to involve the prochoice religious community.

First, a word about terms: The term prochoice is admittedly used broadly, and it is inadequate for many reasons, a few of which are mentioned below. But being for or against choice to varying degrees is how most of the major religious bodies frame their positions, and it is how most polling is framed. So, it is necessary for the purposes of this essay.

A key limitation, as Presbyterian theologian Rebecca Todd Peters says in her 2018 book Trust Women: A Progressive Christian Argument for Reproductive Justice, is that it creates a false binary between prochoice and prolife when most people are both. Prolife in the sense that whatever their view, they recognize that whether or not to have a child is a moral decision, but prochoice in the sense that they also believe that abortion should be legal.2

Second, the broader view of reproductive justice is gaining traction in the religious community. A leading reproductive justice group, SisterSong, defines it as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”3 The reproductive justice framework also includes, as Loretta J. Ross and Rickie Solinger explained in their book, Reproductive Justice: An Introduction, the idea that individuals do not have the ability to make choices on equal terms, when factoring in economics as well as matters of family and community and a variety of life responsibilities.4

Peters told journalist Stephanie Russell-Kraft that embracing the idea of reproductive justice contextualizes rather than isolates abortion, thus providing what she calls a counter-narrative or a counter-framework.

“The three principles that the movement identifies are the right not to have a child, the right to have a child, and the right to parent the children that we have. I think what is so powerful about that framework is that it recognizes that the issue is about parenting and families and motherhood, and the right not to be a mother, and the right to be a mother, and the right to raise our children in healthy and safe environments,” Peters said. “A reproductive-justice framework highlights the difficulties women face when they do have children, in raising those children in a country that tolerates obscene levels of poverty, obscene levels of racism and damage to vulnerable children and families.”5

Cherisse Scott, the CEO and founder of SisterReach in Memphis, Tennessee,6 avers that based on her work as an organizer in the religious community generally and African American Christian communities in particular, discussing anything to do with reproductive matters, no matter what terms are used, can be a “barrier.” She says that navigating and seeking to enhance people’s levels of comfort in talking about sex, reproductive health, and sexuality can be sensitive, particularly in southern areas of the country and small, rural towns where everyone knows everyone and may even attend the same church.

Still, Scott says that among the various iterations of the “Christian Black Church,” some are more “conservative at least in doctrine” than others. However, she says that research conducted by In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda shows that Black women who “identify as Christian” nevertheless “align themselves with being able to make health decisions without hindrance.”

Because this is so, Scott suggests that there may be a need for a “strategy within a strategy” for bringing people along in ways that make the most sense for particular communities, so that no one is marginalized or left behind.7

We should also underscore that access to reproductive health care has both practical and legal implications, often impinging on choice, since, for example, even when abortion is legal, if abortion care is not available, the right to choose is rendered meaningless. In fact, making choice meaningless by making it inaccessible has been the stated antiabortion strategy of most of the Christian Right since the late 1990s.8 This strategy has been and continues to be quite successful.9 What’s more, lack of access to reproductive health care disproportionately affects people who are poor, people who are rural, people who are immigrants, and people of color.

This essay is not intended to resolve all these matters so much as to suggest that there are ways forward for a prochoice religious community that has yet to be fully engaged and organized. It is remarkable that this has not already happened, because it brings a history of deeply considered and evolving moral thought to the table, as well as leaders, institutions, and the legitimacy that comes from serving as central institutions both in communities and, more broadly, in American history.

The reality that vast numbers of religious people are prochoice may be a revelation to those who have been conditioned by the false narrative that people of faith—almost by definition—oppose abortion. The prochoice religious community needs to dismantle the false narrative that faith = antiabortion to offer the hope and possibility of meaningful, even powerfully fresh cultural and political visions, organizations, and actions. That the vast prochoice religious community is under-recognized, under-identified, and under-organized is both the challenge and the opportunity. Taking on this and other false narratives is the first task of this essay, before sharing lessons from a clear-eyed view of the Christian Right about how the religious prochoice community might organize its power post-Roe.

While this essay affords us an opportunity to cast a fresh eye toward a better future, it does not pretend to satisfy every concern. There are no panaceas for issues decades or longer in the making. But if it helps us to better consider how we got to where we are and to imagine a better way forward, it will have done its job.

The History and the Argument

The prochoice religious community has deep roots and a dramatic story in the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS). Initially comprising Protestant ministers and Jewish rabbis, its services were featured in a front-page story in The New York Times in May 1967.10 Many of these clergy had been active in the Civil Rights Movement and, writes Kira Schlesinger in Pro-Choice and Christian: Reconciling Faith, Politics, and Justice, they “connected their theological positions on race and dignity to their commitment to helping women and their families gain safe access to abortion.”11

CCS was the largest abortion referral service in the United States before Roe v. Wade, eventually involving about 2,000 religious leaders who, in addition to helping people obtain safe abortions in the United States and abroad, lobbied for the repeal of abortion laws. CCS members established their own clinics beginning in 1970 after abortion laws were repealed in several states.12

The founders of CCS focused more on the pastoral obligation to help people access safe, affordable abortions than the question of morality. The practical realities for people in need of appropriate abortion care were evident in the 1960s as thousands of people—disproportionately poor women of color in New York City alone—were dying annually from unsafe abortions.13 Meanwhile, people of greater means were able to travel to find ways to get legal abortions, even under the limited circumstances available under the law in New York at the time.14

One woman who saw the New York Times story about CCS contacted them at the Judson Memorial Church in Manhattan, where it was just getting started. They arranged an appointment for her with a doctor in Washington, DC. She took the bus alone. “I don’t know what I would have done without those contacts at Judson Memorial,” she told scholar Gillian Frank. “I think maybe their goal was to reach more impoverished people than I was, but I was just as desperate as any of those people would have been.” She added, “Later I had two healthy beautiful children and a marriage that’s been excellent, and I always felt that this fetus was a potential life, but I had, every month, the potential for life. And if I had gone forward with that pregnancy, the children I have now would not have come to be.”15

The historic role of CCS, and the tradition and function of churches as a sanctuary from oppressive societies and governments, may provide a model for a future in which Roe v. Wade is overturned and criminalization of abortion resumes in a number of states. That time is not yet, but the realities of abortion before and since Roe, and the frontline role of clergy, have all occurred within living memory. This provides a possible model for difficult times to come, including drawing on the wisdom and experience of women, clergy, and medical professionals.

Although the current leadership and engagement of progressive clergy and prochoice religious activists does not get much press coverage, that does not change the fact that it has continued, broadened, and deepened since the era of the CCS. For example, the Religious Institute, a think tank headquartered in Bridgeport, Connecticut, before closing in 2020, had some 15,000 religious leaders in its network and had consulted over the past decade with seminaries from a variety of traditions to help prepare young seminarians for the real world of counseling. These clergy are “first responders” that many turn to in a time of personal crisis.16 The Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC) and Catholics for Choice have also become prominent in state and Washington policy circles.

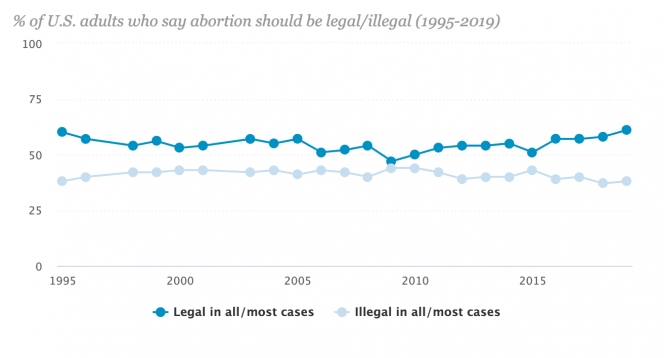

All of this is especially significant in light of the irrefutable fact that most Americans are prochoice. A long-term Pew study of views on abortion between 1995 and 2019 found that “public support for legal abortion remains as high as it has been in two decades of polling. Currently, 61% say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% say it should be illegal in all or most cases.”17 Pew and other reputable pollsters show increasing support for abortion rights.18

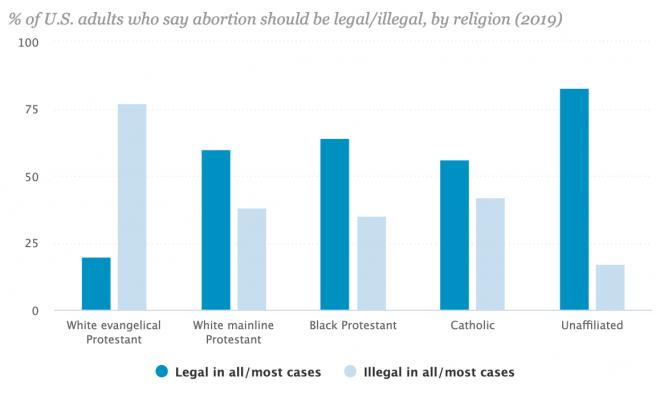

This undermines the false narrative that religious people necessarily oppose abortion access. The Pew data also show that a majority or near majority of the religious community in the Unites States is prochoice, while the Roman Catholic Church, by far the largest Christian group in the United States, is institutionally opposed to abortion in all instances. However, even among that religious community, Pew reported in 2019 that 56% of rank-and-file Catholics believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Moreover, while some mainline Protestant denominations are prochoice, some are not, and others have no position. Pew found that 60% of “White Mainline Protestants” and 64% of “Black Protestants” believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.19 Pew data also show that significant minorities of large antiabortion religious groupings, such as Mormons and White evangelicals, are also prochoice.

The chart below, based on the 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Study, shows prochoice majorities or near majorities in every category measured—except for evangelicals and Mormons, which also have significant prochoice minorities. While the numbers vary from year to year, the basic proportions do not.

Polling shows that support for reproductive rights in the U.S. religious community is broader and deeper than many might think. But polls alone cannot help organizers find the people who will help to build a movement. Fortunately, beyond the numbers, there are historic institutions and well-informed advocacy groups whose leaders and members have played important roles in advancing reproductive rights over the past half-century or so. These institutions include (but are not limited to) the leading denominations of mainline Protestantism as well as most of organized Judaism. It could make a profound difference to know which prochoice religious institutions exist, clarifying the role of other religious organizations, finding the right people within them, and assessing their respective capacities for defending and advancing reproductive rights, access, and justice.20 The sheer numbers, profound cultural resonance, and vast institutional infrastructure of these institutions and the communities they serve suggests great hope and possibility for a resurgent prochoice religious community of historic consequence.

The Challenge and the Opportunity

Once one shakes off the narrative that religious Americans are necessarily opposed to abortion, the political implications are clear. The Christian Right, made up of conservative Roman Catholics and evangelicals, is outnumbered by the growing majority of prochoice religious and nonreligious Americans.

A coherent, sustained political and cultural effort to identify and organize explicitly prochoice religious voters and to train and deploy electoral activists in a systematic way would be a dramatic departure from the way that the prochoice religious community has operated to date, and it would compel changes in its relationship to both allies and adversaries. It would not just be novel, but would arguably be transformational in the history of American politics.

Getting to this point of departure would require recognizing the strengths of the historically powerful and well-organized minority we call the Christian Right. These strengths include the decision of key partners in the antiabortion cause to set aside differences in the name of what antiabortion evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer called “cobelligerence”; the depth and breadth of its organizational capacity, the maturity of its strategy; the experience of its political practitioners; and its alliance with the Republican Party in such matters as gerrymandering and voter suppression.

This can be challenging because there is a tangle of rationalizations that work to preserve status quo thinking. For example, some believe the growing Latinx demographic will somehow organically counter the conservative White evangelicals and Roman Catholics that comprise the Christian Right. Polling by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) in 2019, however, should give pause to such optimism.21

PRRI reports that majorities of all religiously affiliated Hispanics say abortion should be illegal in most or all cases. Opposition is stronger among Hispanic Protestants (58%) than among Hispanic Catholics (52%) and rises to 63% among Protestant evangelicals.

Among younger Hispanic Protestants, just 48% of Generation Z (ages 18–24) and 27% of Millennials (ages 25–29) support legal abortion. The numbers are similar among Hispanic Catholics, of which 55% of Gen Z and only 38% of Millennials support legal abortion.

Thus, the trend is not particularly promising. This may be in part because the Christian Right has long sustained antiabortion organizing efforts in these communities, notably via the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference (NHCLC), an evangelical organization headed by Samuel Rodriguez and based in Sacramento, California.22

The creation of a sustainable prochoice religious movement, perhaps marked by a number of distinct and independent institutions or organizations that are not defined by the ups-and-downs of the electoral cycle or by the fortunes of individual politicians, or the tactical decisions of political parties, would be not just a departure, but also a difficult journey. Daniel Schultz, a minister in the United Church of Christ and author of Changing the Script: An Authentically Faithful and Authentically Progressive Political Theology for the 21st Century, said this could be messy, because democracy itself is messy. There is no “transcendent” path to social change, he insists. “Until the Kingdom come, those who want to create and sustain social change are stuck with morally ambiguous involvement in the world of partisan politics.”23

Wading into the messiness of democracy would mean making a broad assessment of the political landscape with an eye to the opportunities and obstacles.

A much-ignored part of the political landscape is that 100 million eligible voters did not participate in the 2016 election. This number represents those who were registered but did not vote combined with those who could have voted, but were not registered.24 The antiabortion Christian Right, however, is acutely aware of this large pool of potential supporters—and opponents—and over the last 40 years has aggressively sought to identify those most likely to be sympathetic and target them for registration, education, and electoral participation. The prochoice religious community has not.

“We projected that there would be potentially as many as 50 million Christians who … would stay on the sideline,” Jason Yates, CEO of My Faith Votes, a Christian Right voter engagement organization, said in 2016. “That is an overwhelming number and a huge amount of influence. So, we’re doing a number of things to really motivate and equip Christians to vote in these midterm elections.” Yates said that there are about 90 million evangelical Christians eligible to vote and between 25 million and 35 million who regularly do not.25

The Family Research Council, the premier political organization of the Christian Right with affiliates in 35 states, sustains projects across the election cycle to identify and develop their voter pool and turn their people out in election years.26

Not satisfied with their successes of the past decade—notably the election of Donald Trump—these groups continue to refine their methods. Christian Right pollster and strategist George Barna said that it is risky to assume that registering new voters in theologically conservative churches will necessarily net ideologically conservative voters. “Future registration efforts,” he said, “need to be carefully orchestrated to prevent adding numbers to the ‘other side.’”27

Barna’s point about taking care whom to register and activate is supported by a study of nonvoters by the Knight Foundation that found that most nonvoters are prochoice. The nearly 100 million eligible Americans who did not cast a vote for president in 2016 represented 43% of the eligible voting-age population. This is a sizeable minority whose voices went unheard. This happened, in part, because political groups, pollsters, and parties tend to focus most of their attention on already registered and “likely” voters. As a result, relatively little is known about those with a history of nonvoting. While the Knight study did not focus on religious affiliation, it did find that of 12,000 “chronic non-voters,” a clear majority—56%—believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. The number of supporters rises to 63% among young people ages 18–24.28

Still, it is important to note that a Pew study of “voting-eligible non-voters” in 2016 came to different conclusions about the composition of this group. While Knight found little demographic difference between the voting and nonvoting public, Pew reported “striking demographic differences” and “significant political differences as well.” “[N]onvoters were more likely to be younger, less educated, less affluent and nonwhite. And nonvoters were much more Democratic.”29 The discrepancy in the findings of these major studies underscores that while nonvoters are generally not well understood, there is nevertheless compelling data that suggest that a majority is prochoice, regardless of religious views. It also illuminates why Barna advises the Christian Right to seek nonvoters carefully—to avoid making unforced errors in something as basic as voter registration. Once again, it is important to underscore that the Christian Right makes extraordinary efforts to find voters likely to be sympathetic to their cause,30 while the prochoice religious community does not.

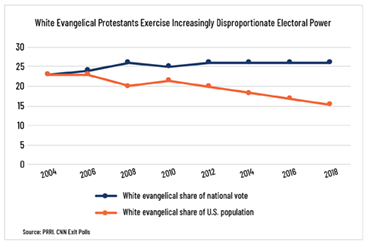

Meanwhile, the Christian Right’s approach to the long game of electoral power politics has resulted in the Christian Right minority, led by White evangelical Protestants, exercising electoral power vastly disproportionate to their numbers. From 2006 to 2018, the White evangelical Protestant share of the national vote increased from 23% to a steady 26%, even while its share of the population declined from 23% to 15%.31

The Power Is Not in the Polls; It’s in the Organizing

There is no analogous organizing on the moderate-to-liberal/left part of Roman Catholic or Protestant Christianity—or any other elements of the religious community—with the broad political and electoral vision and ongoing development of related skills and practices that define the Christian Right.

On the plus side, the million-member United Church of Christ maintains a voter education program around its many issues, which includes but does not necessarily prioritize reproductive justice. They offer an elections tool kit to guide congregations in how to conduct voter registration drives and candidate fora without running afoul of the nonprofit tax laws.32 Likewise Reform Judaism has sought to mobilize their voters (with an aim to 100% voter participation in 2020), combat voter suppression, and engage student voters—but are not highlighting issues.33 And Interfaith Alliance (although it has no position on abortion) produced a helpful guide for voters, churches, and what candidates for public office need to know about religious diversity for the 2020 elections.34 These piecemeal approaches, however, highlight the difference with the Christian Right’s comprehensive, long-term approach to building for political power.

The Parachurch View

Parachurch ministries within modern evangelicalism helped make what we now know as the Christian Right possible, and there are lessons to be learned from them. These are trans-denominational organizations with a religious mission that operate outside of, but not necessarily in conflict with, and often in cooperation with denominations. Among the best-known are Youth for Christ, Focus on the Family, Youth with a Mission, and Campus Crusade for Christ (now rebranded as Cru).35 Such organizations helped pave the way for political parachurch organizations such as the Moral Majority led by Jerry Falwell Sr. and later the Christian Coalition led by Pat Robertson.

These organizations included political and not just religious elements, and in the case of Focus on the Family, they created a national network of public policy and electorally focused organizations, now known as the Family Policy Alliance. The Alliance operates in three dozen states, and its members are also affiliated with the Family Research Council and the legal network, Alliance Defending Freedom.36 Later parachurch organizations brought a maturation of the concept to meet contemporary life, notably the Promise Keepers. This group holds a deeply political vision while maintaining an (arguably disingenuous) public stance of being apolitical.

A 2019 report by Political Research Associates, Playing the Long Game: How the Christian Right Build Capacity to Undo Roe State by State, observed, “Creating organizational infrastructure around a long-term vision of the future was necessary to launch the kinds of political assaults on government and governmental policies that are currently shocking the system.”37

It may be surprising to some that parachurch organizations are not always led by clergy. For example, James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family, was a pediatric psychologist, and Bill McCartney, founder of Promise Keepers, was a college football coach. Clergy are not always the obvious or natural leaders for large organizations that are not religious denominations. But there are exceptions. Another interesting characteristic is that these and other parachurch organizations draw on individual members of conservative denominations, while remaining entirely separate from them.

Parachurch organizations evangelized, recruited, and trained people in theologies, skills, and ecumenical organizing activities that denominations could or would not. They paved the way for the more aggressive political operations that have emerged, matured, and gained real political power in recent decades.

The multi-faith, multiracial Poor People’s Campaign led by Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, has the stirrings of a possible political movement outside of traditional religious denominations. It’s Mobilizing, Organizing, Registering, and Educating (M.O.R.E.) project planned three stops in 22 states between September 2019 and June 202038 before it went online due to the COVID-19 crisis. Beginning in September 2020, the Campaign also sought to turn out 1,000,000 voters for the November election.39

There may be much to be learned from this initiative even though reproductive rights, access, and justice are not a formal focus. Instead (as discussed below), the Campaign argues that the Christian Right and the antiabortion movement use the issue to mask a racial and economic agenda that they say is inconsistent with Christian teaching and is undermining democracy.40

That said, the multi-faith and multiracial nature of the prochoice community makes organizing generally more complicated than for the Christian Right. For example, the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), housed at Harvard University, found Republicans are both racially and religiously more homogeneous than Democrats. The study found that 70% of Republican primary voters in 2016 were White Christians, while Democratic voters were much more diverse: 31% were White Christians, 22% were non-White Christians, and 12% belonged to non-Christian religious groups (Jews, Muslims, Hindus, etc.) or said that their religious affiliation was “something else.”41 This reality underscores how greater religious diversity means promoting greater religious literacy and a deeper grounding in historic notions of religious freedom, religious pluralism, and separation of church and state. Although it may sometimes be challenging, it is a necessity, not an option.

Avoiding False Equivalences

It is important not to engage in false equivalences between the Christian Right and the Religious Left. The visibility of a few activists and liberal politicians who happen to be articulate about the way that they link their faith to their values and political agenda is not necessarily evidence of a Religious Left (some prominent commentary notwithstanding). Neither is the existence of some politically active liberal religious leaders necessarily evidence of a Religious Left. There have always been politically progressive people who are religious and religious people who happen to be progressive. But that is not the same thing as having a large-scale, sustained, well-resourced, and perennially renewed religious and political movement analogous to the Christian Right.42

Some may argue that the Religious Left is differently organized and operates differently than the Christian Right. To whatever extent that may be true, it then must also be true that this Religious Left has been overwhelmed at almost every juncture by the sheer organizing capacity and electoral power of the Christian Right, and it needs to reconsider its approach. This is certainly true on matters of reproductive rights, access, and justice.

But it does not have to be this way.

What is perennially ballyhooed as an emergent Religious Left by some media, pundits, and interest groups is not necessarily prochoice.43 In fact, prochoice religious people and their concerns have been largely marginalized in public life generally and the electoral arena in particular.

One remarkable example of this played out at the 2020 Democratic National Convention. Although reproductive choice and justice received the requisite mentions one would expect from an officially prochoice party, there was nothing from an explicitly prochoice religious perspective. However, Fr. James Martin, a liberal Jesuit priest, closed the convention with a prayer in which he asked God to “[o]pen our hearts to those most in need.” On his list was “[t]he unborn child in the womb.”44

Three days later, Roman Catholic Cardinal Timothy Dolan opened the Republican National Convention with a prayer in which he also listed those for whom we must pray, including “the innocent life of the baby in the womb.”45 Speakers throughout the RNC linked their antiabortion views with their vision of God and country.

While the GOP has sought to solidify its base, the Democrats chase antiabortion religious voters on the margins, and both parties ignore the vast prochoice religious community in the United States.

Beyond the parties, prochoice religious people may be working alongside those with whom they agree on such matters as immigrant, criminal, and racial justice—but have to set aside matters of reproductive choice and justice and work on those things elsewhere, in some other way.

A decade ago, Carlton W. Veazey, an African American Baptist minister and then-president of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC), highlighted this problem: “A Religious Left that is unwaveringly committed to protecting religious freedom and enabling religious pluralism to flourish,” he wrote, “should speak with one voice against all attempts to violate church/state separation, including in areas of reproductive decision making.”46

“The current and prospective Religious Left faces a significant challenge,” Veazey added, “in how and even, for some, whether to address reproductive justice.” He posed a choice that remains as true today as it was then: “The options are clear. We can continue to give lip service to the issues of reproductive justice, rejecting these issues as too divisive. Or we can directly address them because they are of the most profound concern to women and men throughout the world.”47

A prospective Religious Left, or sectors of a Religious Left with unambiguous views on reproductive rights, access, and justice, need not ape the structure and methods of the Christian Right—although it could probably take some lessons from it.48 Whatever organizations it might develop would need to be consistent with its own values in its organization and methods. Some such organizations might be affinity groups within or outside of denominations. They might be ecumenical or multi-faith. They may be local, regional, or national. They might even be loosely modeled on evangelical parachurch organizations. There may be no right way or wrong way, except to begin. (See strategic considerations, below.)

Meanwhile, there may be a historic shift underway among some progressive evangelicals. The Poor People’s Campaign, a contemporary revival of the Poor People’s March on Washington, launched by Martin Luther King Jr. prior to his assassination, does not have a position on abortion. However, its leaders argue that the antiabortion politics of the Christian Right are part of a long-term effort to sustain White supremacy as well as social and economic injustice in the United States.49 Campaign co-chair Rev. Barber says, “You know where they actually started? They actually started being against desegregation and when that became unpopular, they changed the language to be about abortion.”50 Author Katherine Stewart agrees, and in her 2020 book, The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism, she details the way that abortion was developed as a rallying issue for the nascent Christian Right in the 1970s, partly out of a recognition that old-time racial politics was no longer going to work.51 Noting that the 2020 March for Life featured Donald Trump—the first president to address the event—the Campaign’s Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove wrote, “The ‘pro-life’ movement is killing democracy in America.”52

The shift in the view of the Poor People’s Campaign is one, but far from the only, way that the prochoice religious community, like the rest of the prochoice population, is ideologically more diverse than anything that would fit neatly into a Religious Left.

Therefore, for purposes of building a prochoice religious movement of any kind, it is important to note that a wide swath of the prochoice community is not necessarily progressive. Many are moderate, conservative, or libertarian. Pew reported in 2019:

Conservative Republicans and Republican leaners are far more likely to say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases than to say that it should be legal (77% vs. 22%). Among moderate and liberal Republicans, 57% say abortion should be legal, while 41% say it should be illegal.

The vast majority of liberal Democrats and Democratic leaners support legal abortion (91%), as do three-quarters of conservative and moderate Democrats (75%).53

The implications of this are important, as the various elements of the prochoice religious community look to one another to figure out how to achieve their common purposes, rather than looking first to opponents in search of elusive “common ground.”

Indeed, the conversations that most need to take place are within the prochoice religious community itself. One effort to realign the moral narrative without having to capitulate to antiabortionism in the name of common ground is underway in Texas. Sonja Miller of the Just Texas project of the Texas Freedom Network says that antiabortionism is “actually not the majority opinion; it’s the loudest, most dominant voice. So it’s absolutely essential that people of faith who fully affirm women accessing their own moral agency and making their own decisions step up and speak out affirming that.” Just Texas is designating “Reproductive Freedom Congregations” in the state. They report that twenty-five congregations have received the designation as of August 2020, with more in development.54 Similar projects are underway in several other states as well.

Since there is real ideological (and not just religious) diversity in the prochoice religious community, one of the lessons is, as Jean Hardisty and Deepak Bhargava said in their influential 2005 essay, “Wrong About the Right,”

We ought to tolerate a diversity of views and think strategically about how to align them to common purpose rather than seek a homogeneity we falsely ascribe to conservatives.55

Don’t Get Buried Under Common Ground

The problem of the marginalization of reproductive rights, access, and justice is illuminated by election-year efforts by the Democratic Party and related interest groups that are not as inclusive as they may appear.56

One faith outreach effort in 2020 has gone so far as to say it is “teaching Democrats how to speak evangelical”—as if evangelicals were the only, or at least the most important, religious demographic worth reaching.57 The initiative echoes the past when it argues that Democrats should focus their message to evangelicals on efforts to reduce the number of abortions rather than criminalization of abortion.58 This is the same argument that antiabortion figures in the Democratic Party have been making since at least the 2008 election, with little to show for it.

The reason for this failure may be that it is a funhouse mirror image of the central strategy of the antiabortion movement since the 1990s. This is when it began to focus on legislative efforts intended to reduce the number of abortions by restricting access to abortion services59—while ignoring or opposing the things that actually do so, such as sex education and access to contraception and reproductive health services. The Christian Right’s incremental approach to shrinking access to abortion services has led to numerous restrictions in the states, particularly since the Republican landslide of 2010, which created antiabortion legislative majorities in many states.60 Meanwhile, the abortion-reduction argument fell flat in the Democratic Party.

Continuing and compounding this problem is that those Democrats looking to get a bigger slice of the pie of religious voters in election years are not necessarily looking for prochoice voters. This is particularly so since “faith” became so conflated with “White evangelicals” and “White Catholics.” Democratic strategists have been targeting them, with little success. The values and programmatic ideas related to reproductive rights, access, and justice are often downplayed out of fear of alienating ostensibly “gettable” members of these groups.

Daniel Schultz wrote, “trying to make the Democratic Party more ‘faith friendly’ in order to draw in ‘persuadable’ social conservatives is, frankly, a waste of resources … there is no need to water down the identity of a nascent Religious Left by soft-peddling core social beliefs in order to reach swing voters.”61

Schultz’s point is important, in part because there are few sustained efforts to increase the size of the electoral pie by registering and engaging voters across the election cycle, let alone identifying, registering, and mobilizing a specifically prochoice religious electorate.62

“A truly progressive Religious Left will need to stand its ground on abortion,” Schultz has also written. “A truly faithful movement will need to seek hope and freedom for women beyond medicalized regulation of their bodies. Only when we understand that women must be empowered as a principled matter of justice will we be able to break new ground on this social, political, and religious dead zone.”63

In the religious community, there has been a temptation and a tendency to seek common ground with opponents. As worthy as those conversations may be, of far greater importance to the future of reproductive rights, access, and justice are conversations among those who already agree that when to have a child or terminate a pregnancy is a moral choice that people make all the time, taking into consideration their life situation and the needs of their current and future families. Most of the world’s major religious traditions recognize64 that people are fully capable of deciding when and under what circumstances to make that choice without direction from the state and other uninvited agencies.

Derailing False Narratives, Including the One about the “Nones”

If and when the prochoice religious community, broadly writ, seeks to more profoundly organize to defend and advance its values in public life, blowing up false narratives will be not only necessary but also possible.

First, the existence of a multi-faith prochoice majority or near majority derails the false narrative that “religious” or “Christian” equals antiabortion and that secular means “pro-abortion.” As noted above, the very existence of formal prochoice positions and activities of many of the leading historic denominations of Christianity and Judaism refutes the false narrative. It is also worth noting here that there are many nonbelievers and otherwise religiously unaffiliated who are antichoice. Indeed, the percentage of antiabortion “Nones” is about the same as the percentage of prochoice White evangelicals.

Another false narrative that is derailed by the facts is: just because people disaffiliate from a denomination, or no longer identify with a specific religious tradition to a pollster, that does not necessarily mean that they are not religious or that they hold or no longer hold particular views on matters of reproductive choice.

What about the Nones?

The polling phenomenon of the “Nones” is a trend that has received a lot of media attention, but finding significance can be elusive when trying to make sense of the political landscape for reproductive rights, access, and justice. A 2019 study by Pew found that the category of the Nones—that is, people who say they have no formal religious affiliation or identity—is increasing, particularly among young people, even as the percentage of Americans who identify as Christian has continued to fall.65 The trend that fewer people now claim a specific religious identity is part of the related trend of the steep membership losses experienced first by mainline Protestant denominations and more recently by Southern Baptist and Roman Catholic churches.

Because of the centrality of Christianity in U.S. history and culture, signs of historic declines are certainly newsworthy. However, there may be little going on of any consequence in terms of people’s values or their political or electoral behavior.

Pollsters have observed that the Nones “are far from a monolithic group.”66 Thus, Baylor University religion scholar Philip Jenkins urges caution in drawing conclusions about them. The Pew study “carefully points out,” he stresses, “that ‘None’ does not equal no religion, or no religious belief, and you should dismiss any media report that suggests otherwise.”67 (In 2012, Pew reported that “a third of the unaffiliated” said that religion was very important, or somewhat important, in their lives.68)

“A typical ‘nothing in particular’ None,” Jenkins says, “is a person who believes in God and might pray regularly, but who rejects a religious affiliation. Given the religious breakdown of the larger population, most of the Nones come from Christian backgrounds, so that the religion that they choose not to admit belonging to is Christianity.”

Jenkins says that the recent uptick the number of the Nones tracks with widespread revulsion to the overt greed and harsh politicization of parts of conservative evangelicalism, and to the ongoing Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal. Therefore, he sensibly argues, many would rather not identify with these groups and Christianity in general, even if in earlier years they may have been unaffiliated, but still willing to identify as Christian.69

These caveats are important for purposes of thinking about religious community support for reproductive choice and justice. Pew data show that the Nones are more prochoice than society as a whole, and that their numbers are growing. However, the Nones are not any more explicitly organized on matters of reproductive rights, access, and justice than the broad prochoice religious community; what’s more, a significant fraction—about a quarter—are not prochoice.

It is also important to note that while the decline in religious identity and institutional membership is real, less well recognized and reported is that the decline in organizational identity and membership is not unique to religious institutions. In fact, there have been long-term declines in membership organizations across the board for decades, as detailed by Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam in his 2000 book Bowling Alone. “For the most part,” Putnam wrote, “the younger generation (‘younger’ here includes the boomers) are less involved both in religious and in secular activities than were their predecessors at the same age.”70

While most popular reporting on and, unfortunately, political analysis of the data is framed in terms of the decline of religious belief and membership, the same data looked at from an organizing perspective tells a different story—a story of opportunity in the midst of social and demographic change. To be sure, the opportunity is not without challenges, but a clear-eyed understanding of both the opportunity and the challenges makes planning to organize possible.

Yet it is the organizing piece that is typically missing from published news, opinion, and analytical discussion of these trends. Of course, a prochoice religious movement would not be electoral alone. It would be rooted in a broader religious and political culture in which these values are central. The point is that the absence of any vision or practice of electoral democracy in this sector illuminates the necessity of having the power to make much of a difference.

To build a broader religious and political culture in which prochoice religious values are central, it will be important to set aside the assumption that demography and polling are necessarily political destiny. The Christian Right has proven that demography is not political destiny. An important reason for the success of the Christian Right has been the absence of meaningful counter-organizing that contends in the democratic marketplace and encourages the development of relevant political knowledge, skills, and organizations. This is a problem that can be solved.

The War of Attrition against Prochoice Christian Churches

The prochoice religious community in the United States and the institutions that inform it exist in a context of contending forces. The effects of all this goes unmeasured by pollsters and tends to be ignored by reporters and academics—even among those who attribute dismay about the “culture wars” as a reason for the decline in church membership.

Leading mainline Protestant denominations—all of which are prochoice—have been the target of a decades-long war of attrition waged by outside conservative evangelical and Catholic-led organizations working in consort with conservative and antiabortion factional dissidents. This multifaceted effort has sought to degrade and divide the historic communions of mainline Protestantism—largely for the purpose of diminishing their positions on economic and social justice generally, and reproductive choice and justice in particular—and reducing their capacity to advance their views in public life. The right-wing organizations behind the attack are still active and are a relevant part of the religious/political landscape.

The leader of this war of attrition has been the Institute on Religion and Democracy (IRD), based in Washington, DC, and underwritten by some of the same conservative foundations that helped found and sustain such organizations as the Heritage Foundation and the Ethics and Public Policy Center (EPPC) in the 1970s.71 (The EPPC, led by Catholic neoconservatives, also hosted the 1996 meeting that forged the strategy of seeking state legislative restrictions on abortion access.72)

IRD for many years organized and caucused with conservative and prolife factions in the mainline denominations under the rubric of the Association for Church Renewal.73 Some of those “renewal” groups were also part of the ecumenical National Pro-Life Religious Council,74 a subsidiary of the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) and long led by Fr. Frank Pavone, the militant leader of Priests for Life. Some are members to this day.75 The NRLC in turn was founded in 1967 as a project of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. It was separately incorporated in 1973 in response to Roe v. Wade. It became ostensibly independent and ecumenical out of the desire to attract Protestants.

One telling project of the National Pro-Life Religious Council was a 2003 book-length critique of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC), an interfaith organization founded in Washington, DC, in 1973 in the wake of Roe v. Wade. (The founding members included several major institutions of Protestantism and Judaism.) The authors arrogated to themselves the role of judging what is and is not authentically Christian, concluding, “RCRC does not represent the Christian faith in the matter of abortion.”76 RCRC never claimed that it did—being an interfaith coalition of prochoice religious communities, founded by them in the first place. Additionally, Christianity has no one view on these matters. This is unsurprising since Christianity has no central authority and no one orthodoxy. For the authors to imply that it does, and that they speak for it in this way, is hubris and is not to be confused with orthodoxy.

Texas Freedom Network/Just Texas)

The story of the long-term war of attrition against the prochoice denominations of mainline Protestantism is beyond the scope of this essay, but it is important to note that once again, an outside agency sought to pick apart the prochoice religious community: in this instance by inflaming differences of views among the members of RCRC and the organization of the coalition itself. Due in part to such efforts, RCRC is no longer a coalition, but it remains a freestanding organization, continuing to work with a wide swath of prochoice religious community.

As happens with any broad movement, there is at once greater ideological diversity than sometimes meets the eye, and overlap among groups and individuals. In this instance, it is important to see that there is sometimes a relationship between conservative and progressive antiabortion figures that animate religious antiabortionism.

Illustrative of this seeming paradox is that the late Richard John Neuhaus, one of the endorsers of the anti-RCRC book, was also a founder of IRD. Some other of the endorsers are members of the more progressive Consistent Life Network,77 formerly known as the Seamless Garment Network. This group grew out of the “Consistent Ethic of Life,” views of the late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago who held that a prolife view must not be limited to opposition to abortion, but must include opposition to capital punishment, economic and social injustice, euthanasia, and militarism in terms of Catholic principles of valuing the sacredness of human life. The Consistent Life Network, like the National Pro-Life Religious Council, also includes some progressive evangelicals and mainline Protestants.

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church has sought to silence prochoice dissidents for decades. Throughout the 1970s and mid-1980s, some priests, nuns, and theologians publicly argued that the Catholic values of conscience and discernment created space for a prochoice Catholicism. Furthermore, they argued that in a pluralist society, Catholics had no right to impose their values through the legislative process, likewise creating space for prochoice Catholic public officials. These Catholics were largely silenced beginning with the papacy of Pope John Paul II—most famously in 1984 after some 100 signed a statement in The New York Times stating that Catholics could be prochoice.78

While working to silence prochoice Catholics, conservative elements of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops openly came alongside the Republican Party to signal that practicing Catholics could not vote for prochoice candidates. Catholic parachurch groups, such as Catholic Answers, EWTN (Eternal Word Television Network), Catholic Vote, and Priests for Life have issued voter guides that reflect this view.

These groups have been active in broader ways as well. Priests for Life conducted campaign skills trainings during the 2016 election, for example, on behalf of Ohio Right to Life.79 Catholic Vote, run by prominent pro-Trump Catholics, in 2020 tracked the cell phones of people who attend Mass in order to gather data about their voter registration status and voting history. The goal was to develop profiles for targeted outreach in swing states. This method, called “geofencing,” has also been used to identify and track White evangelical churchgoers as potential voters.80

Meanwhile the stakes in the decline of the prochoice Christian churches are not limited to reproductive rights, access, and justice. As Robert Putnam observed in Bowling Alone, the trend of overall decline in membership organizations, including churches, raises concerns about the loss of opportunities for people to learn and practice relevant knowledge and skills for engagement in democracy. He observed that churches “are one of the few vital institutions left in which low income, minority and disadvantaged citizens of all races can learn politically relevant skills and be recruited into political action.”81

The decline of prochoice religious institutions with democratic polities (in which people choose their own leaders, develop their own theologies, and make public policy choices that flow from them) has allowed more authoritarian, conservative, and patriarchal institutions to gain in influence at their expense, and arguably at the expense of the culture and practice of democracy itself.

Inside the Organized Prochoice Religious Community

Even as these mainline Protestant denominations are in some sense bastions of support for reproductive choice and justice with long histories that predate Roe v. Wade, some are internally divided, due in part to the gridlock generated by internal factions with the assistance of outside interests. This leaves many frustrated.

“[M]ost of the statements supporting a woman’s right to a safe, legal abortion are several decades old,” writes Episcopal priest Kira Schlesinger in her 2017 book Pro-Choice and Christian: Reconciling Faith, Politics, and Justice. She notes that it’s “almost as if the mainline position has thrown up its hands and ceded this ground to the Roman Catholic Church and more theologically and politically conservative evangelical and fundamentalist churches.” She explains,

It’s so personal, so morally ambiguous and fraught, such a third rail, that it’s rarely discussed even in more progressive Christian circles. I attended a notoriously liberal divinity school [Vanderbilt] that prided itself on a commitment to social justice, but there was virtually never a mention of abortion or reproductive rights except in passing.

She concludes,

Even as mainline denominations make statements in favor of other social justice issues, like LGBTI rights, an end to the death penalty, sensible gun legislation, and support for racial justice organizations like Black Lives Matter—they remain remarkably silent on issues of reproductive justice.82

Nevertheless, the voices of the traditional advocacy for reproductive choice and justice have not been silent, even if they have not always been heard. Tom Davis, a minister in the United Church of Christ and one of the founders of the Clergy Consultation Service, wrote in his 2005 book, Sacred Choices: Planned Parenthood and Its Clergy Alliances, “no prophetic faith can leave a group behind. It is, in fact, the very essence of prophetic religion to seek justice for the very group that is left out.”83

This situation is not limited to seminaries and denominations. Books about religious social justice often fail to incorporate reproductive justice, perhaps for the reasons Schlesinger identifies. Alternatively, it may be because reproductive choice, access, and justice are just not part of their vision. This omission is matched by secular books on the politics of reproductive rights that fail to even mention the prochoice religious community.

Whatever the reasons, the result has been to cede the religious argument to the Christian Right and to ignore the reality of the vast prochoice religious community in the United States.

It needn’t be this way.

Christian author and theologian Rebecca Todd Peters spoke to this in 2019:

While outspoken evangelical and Roman Catholic leaders continue to promote the idea that Christianity is anti-abortion, this belief is both a misrepresentation of Christian history and a misrepresentation of what many committed Christians today believe. According to a 2018 PRRI poll, only 14 percent of people hold that abortion should be illegal in all cases. Moreover, mainline Protestants like Presbyterians, Methodists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and the UCC are most opposed to making abortion illegal in all cases with only 5 percent of that group supporting a total ban on abortion.84

Peters added that anyone considering the future of reproductive choice and justice in the United States must take to heart the idea that religious freedom belongs to everyone and not just to religious conservatives. She wrote,

refusing to codify traditionalist, conservative religious beliefs into law isn’t a violation of anyone’s religious freedom. In fact, it not only protects a large majority of people in this country from the tyranny of patriarchy, it actually protects their religious freedom.85

Carlton Veazey similarly argued in 2009 that religious freedom is essential. (This was also the year that leaders of the Catholic and evangelical wings of the Christian Right formally joined forces to hijack the idea in the form of a manifesto titled the Manhattan Declaration86).

The opposition to comprehensive sex education, HIV/AIDS prevention that includes condom education, emergency contraception and legal abortion comes from religious groups that claim these violate religious beliefs—the underlying message being that the only valid religious beliefs are theirs.87

He also suggested that this was not being addressed by non-Christian Right political and religious leaders.

The failure to appreciate and articulate religious pluralism as a powerful value, often leads to capitulation and compromise on reproductive issues with factions that do not honor the differing value systems inherent in our religiously plural society, as well as the value of religious pluralism itself.88

Jews have also not been silent in the face of assaults on access to abortion and their religious freedom to say when life begins and the nature of choice according to their traditions. “It makes me apoplectic,” Danya Ruttenberg, a Chicago-based rabbi and author who has written about Jews’ interpretation of abortion,89 told USA TODAY in the face of the attempts to criminalize abortion in several states in 2019. “They’re using my sacred text to justify taking away my rights in a way that is just so calculated and craven.”

“This is a big deal for us,” Ruttenberg continued. “We’re very clear about a woman’s right to choose. And we’re very clear about the separation between church and state.”90

Yet many religious and nonreligious people have been boxed into the conservative framing of pitting secular vs. religious values. Scholars at Columbia Law School have argued that this unwittingly reinforces the views of the Christian Right. “We should reject a ‘religion vs. LGBTQ/reproductive rights’ framing for religious liberty claims,” they declared. “For many, religious freedom does not conflict with reproductive justice and LGBTQ equality.”91 Indeed, religious freedom and reproductive rights are not necessarily a mutual contradiction for a majority of the population and maybe even a majority of the religious community.

The fact is that many Americans derive their support for reproductive choice and justice, and LGBTQ equality, through their religious values, not despite them. They find it an affront to their religious freedom to face laws that allow businesses, health care organizations, and others to refuse to recognize the legal and moral legitimacy of their members’ marriages, performed by members of their own clergy, and access to medical care and adoption and foster care services, among other things, that are—or ought to be—equally available to all, without exception. It is also an affront to their religious freedom to be compelled to make moral decisions compromised by the unwelcome assistance or interference from the government and people of different religious views.

Conclusion

The prochoice community is now considering the future in light of what has been lost92—and what more will have been lost when Roe v. Wade is overturned. This essay highlights a powerful source of hope and possibility whose time has come.

There is a vast prochoice religious community with a vibrant history and world changing potential. The customary public platitudes about “faith” notwithstanding, this enormous sector of American society is under-recognized, under-reported on, and under-organized. Because this is so, it is also a virtually untapped source of power and hope for the future of reproductive freedom, access, and justice. Any new long-term strategy will increase the possibility of success by recognizing that this is an opportunity to imagine—and to achieve—a far better future than many may now think possible.

The successes of the Christian Right—won with its Roman Catholic and evangelical wings united—are the result of decades of institution building and theological and political work by a well-resourced numerical minority operating with a strategic vision and theocratic intent. It is of no small historical consequence that they have twisted and abused the idea of religious freedom to establish the right to infringe on the rights of others. The Christian Right has done this in considerable part by employing the tools of electoral democracy to achieve its public policy goals. It has also waged a long-term war of attrition against prochoice religious institutions that continues to this day, bleeding members, churches, and regional groupings in the face of conflict stoked from the outside by politically and religiously motivated actors.

All this has contributed to obscuring certain stubborn facts. Polling shows that both the religious and nonreligious general public is increasingly prochoice. Polling also reveals the vastness and diversity of the prochoice religious community, comprising individuals of varying religious affiliations and identities, and varying degrees of support for the right to choose. But polling is not the whole story. There are also historic prochoice religious institutions and activist networks with profound experience, demonstrated commitment, and the capacity to facilitate access to reproductive health care at a time when both the right to receive and to provide such care is under sustained and systematic attack.

Indeed. Power is not in the polls, it is in the organizing. If it is true, as a 2019 NPR-PBS Marist Poll had it, that 77% of respondents think the Supreme Court should uphold Roe v. Wade93, then it is also true that this reality is not well reflected in politics, policy, and media coverage. This is the challenge and the opportunity for the prochoice religious community to rise to moral and political leadership. The Christian Right has an ideological, cultural, and electoral strategy designed to accomplish their ends, and the prochoice religious community does not. This needs to change. And it could.

There is a potentially powerful cohort of prochoice religious activists and voters, who could be organized both inside and outside of their institutional homes—beyond traditional secular prochoice or religious social justice groups, and also in considered relationship with them. This prochoice religious community could draw upon a vast institutional infrastructure that still exists at the center of American religious life in many communities, in all parts of the country.

Acknowledgments

A project of any significant length of time and text usually benefits from the good thoughts and wise counsel of others, and this essay is no exception. And as always, there are too many who came before to whom I owe debts I cannot repay except to honor them by taking the work forward as best I can. To those who can be named for this project, many thanks go to those who have read, commented, advised, and edited along the way. These include Cari Jackson, Lisa Weiner-Mafuz, Elaina Ramsey, Katherine Stewart, Trishala Deb, Abby Scher, and my colleagues Tarso Ramos, Greeley O’Connor, Patti Miller, and Tina Vasquez.

Building the Cultural and Political Power of Prochoice Religious Communities: Strategic Considerations

The above analysis argues there is a vast prochoice religious community, but that it is marginalized within religious and political organizations and broadly in public life, and is thereby easily divided and kept from becoming politically powerful. Together with the nonreligious prochoice community, they constitute an overwhelming majority of the population and, potentially, the voting population. Taken together, they could become powerful. But the prochoice religious community first needs to discover itself. (To that end, PRA’s “An Annotated Directory of the Prochoice Religious Community in the United States” may help.94)

To politically empower itself, the prochoice religious community needs to create organizations outside of traditional religious institutions. A significant part of the historic success of the Christian Right,95 in both its evangelical and Catholic wings, has come through the organizations and actions of what are called parachurch organizations, operating across denominations—which is to say, outside of, but not necessarily in coordination or in conflict with, denominations. There are certainly already small-scale organizations and projects, but to meet the current challenges, new entities will need to be considered, developed, and scaled up to be culturally and politically significant.

The prochoice religious community needs to envision what trans-denominational organizations of its own might be like. The Christian Right has had the benefit of being more religiously and racially homogeneous. However, organizations of the prochoice religious community will necessarily be religiously and racially more diverse, and the nature of the diversity may vary, depending on locality and region. Navigating differences while building greater unity may be challenging, but the call to do so is at the core of the values of most religious communities—and this usually includes the commitment to the values of religious freedom, religious equality, and separation of church and state.

For these reasons, creating one big national organization may be an unworkable goal, at least in the near term. A more promising series of possibilities would be the creation of trans-denominational groups as state, local, or regional entities—at least as pilot projects to figure out what works and what doesn’t. Although such groups would be separate, they would all need to have some common understandings about their mission at the outset. They would need to be dedicated to finding people who share a vision of creating a politically strong prochoice religious community. Some of these groups may need to be specific to a certain tradition, Roman Catholicism, for example. They might be ecumenical, involving various strains of Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, and others. They might be multi-faith. Most American communities are racially and religiously diverse to varying degrees, so creating such groups ought to be possible. In the spirit of ideological diversity, some may be more oriented to a choice point of view, others with a justice point of view. Still others may want to consider a multi-issue approach, in the manner of what Religious Left organizations might be like if reproductive choice, access, and justice were part of the agenda. All should be considered, encouraged, supported, and understood to be part of a greater whole with a common mission.

An important consideration will be whether these groups would be more or less single issue, or have a more integrated, multi-issue view. For example, are reproductive rights and health care actually separate from human and civil rights and health care in the broadest sense of those ideas? These questions are already foundational to the conversation on reproductive rights and access, and they are likely to become even more so as religious organizations and leaders that have existing, deeply considered social visions begin to more fundamentally engage the politics of all this.

The mission of the groups, whatever their composition, must be grounded in the basic values of religious freedom, religious pluralism, and separation of church and state. Without this grounding, it is difficult to relate to the constitutional and legal issues, and to explain how a variety of views on abortion can or even should be accommodated in a pluralist society—even as the prochoice religious community strives to regain what has been lost, and hold to a vision of improving on what used to be.

This brings us to the second main type of multi-faith organization: political organizations, whether state, regional, or national, that are able to develop an electoral constituency not only as a voter base but also as a permanent source of skilled political workers, candidates, and officeholders. In this vision, the knowledge and skills necessary for electoral politics must be foundational to building for power sufficient to regain what has been lost and to move beyond it. Such organizations will understand that the political education and outreach activities they engage in are ongoing processes across election cycles, and thus they need not be reinvented each election cycle or organized solely around a candidate or party.

A movement based on democratic values necessarily requires a deeply held vision and a profound knowledge of the skills it takes to sustain it and to make it so.

It is important to distinguish between this kind of political organization and traditional educational interest groups, lobbies, and coalitions. What would be different would be that these organizations would have a set of unambiguous moral principles (not policy goals) toward which they are working in the post-Roe era, and will rally people who agree with these principles; who want to culturally and politically pursue them; and seek the resources and skills to infuse them into culture, government, and law. This means creating lasting institutions and organizations to carry this forward.

To sustain a vision of building for power, it is essential not to wait for permission from existing national organizations (whether religious institutions, political parties, or advocacy groups) to begin to act. There is also no need to wait for a national organization to engage in “faith outreach” efforts. Independent entities can set their own priorities and make their own decisions, albeit in consultation with friends and allies, as appropriate. In that spirit, it will be important, for example, for groups to keep their own contact lists and ask that candidates and consultants share information and not hoard it. A predatory culture of political consulting and egocentric politicians has contributed to getting us to where we are.

All this may require creating or repurposing a third kind of organization, a clearinghouse, and a strategy and training center, to create or to point people to appropriate resources and to conduct ongoing organizer, campaign, and candidate schools. Once established, trainings can be conducted anywhere, especially as a cadre of experienced trainers is developed. These trainings would not necessarily be a substitute for existing training schools (although they could be) but perhaps more as a supplement to fill in the missing elements of what is needed for the prochoice religious community.

Creating a culture of learning will be essential. This will not only include education in connecting religious values to prochoice public policy and politics, as is already commonly practiced, but ongoing education on the history and nature of the Christian Right, the antiabortion movement, and the ongoing evolution and evaluation of strategy, tactics, and campaigns, as well as the history of the prochoice religious community and the lessons learned. As in any endeavor, the competition changes and adapts to new circumstances, and all sides learn from their experiences, or risk repeating their mistakes. The prochoice religious community must have the capacity to integrate political lessons into ongoing tactical and strategic thought.

In support of such efforts, for example, the prochoice religious community may want to develop—sooner rather than later—short, well-produced educational videos aimed at highlighting prochoice religious leaders in politics instead of allowing them to be marginalized. There should be a recommended reading list. And if the existing literature is insufficient (which it probably is), the literature will need to be created by underwriting and commissioning books and articles, and their distribution for maximum impact. There should also be remote online education and training programs.

The prochoice religious community should also have its own mission-oriented online magazine. Such a publication could be located either within another publication as an incubator/fiscal sponsor, within the center, or as a freestanding startup. Similarly, it may require a specialized publishing house or imprints from several publishers to meet the needs of a vigorous new movement. Encouraging, supporting, and promoting writers in this area will be important. Arguably, the many topics related to the prochoice religious community could and should also be foci for any number of existing outlets.

These things could be underwritten by traditional philanthropies and developed and incubated through nonprofit organizations. But they merit the attention of religious and political philanthropists as well. And while some of these things could happen quickly, most will take time, planning, and development.

In the interests of time, establishing such a center within an existing institution to serve as an incubator and fiscal sponsor might be a consideration.

This center should not be located in Washington, DC, where there is too strong a centrifugal pull into the details of policy, legislation, and the courts. The development of a prochoice religious community of sufficient cultural and political power to restore and advance what has been lost cannot afford to be mired in the contemporary details of government and related political culture. This is necessarily a matter of both grassroots political development as well as traditional publishing, think tank, and training center type activities. The location of a center might be better in a city or state with a supportive prochoice religious community, such as Cleveland, Ohio, headquarters of the United Church of Christ. New York City is home to The Episcopal Church, United Methodist Women, and many prochoice Jewish organizations. Chicago, Illinois, is headquarters to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Chicago Theological Seminary. Boston is home to the headquarters of the Unitarian Universalist Association, Episcopal Divinity School, and more.

These are just ideas and are not intended as a plan, although obviously some or all of them could become part of a plan going forward.

The Power of Parachurch: A Response

By Rachel Tabachnick

This response is an elaboration on the power, possibilities, and challenges of parachurch from the perspective of observing decades of successful organizing of the Christian Right and its coordination with other conservative infrastructure.

One definition of parachurch is a “voluntary, not-for-profit associations of Christians working outside denominational control to achieve some specific ministry or social service.”96 Parachurch organizations usually pursue IRS nonprofit designation as 501(c)(3) public charities. They have paralleled and sometimes exceeded the dramatic growth in the total number of nonprofits in the United States over the last forty years.97 Parachurch organizations fall into numerous categories: evangelism, relief and development, education, publishing and broadcasting, advocacy, and more. The advocacy sector only includes about 5% of the larger parachurch world but includes many powerhouses of the Christian Right.

Bypassing Traditional Institutions

Parachurch growth also has paralleled that of conservative think tanks, which began to have dramatic growth in the mid-1970s. Self-described “free market” think tanks were founded in almost every state and networked by national organizations as a way to circumvent the existing traditional political and academic institutions to bring about cultural and political change.98 Decades of direct marketing to both political elites and the public has increasingly empowered this conservative infrastructure to now work inside the system, rebuilding institutions in their image.

In his book Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite, D. Michael Lindsay describes parachurches as the “fulcrum of evangelical influence.”99 Lindsay calls business leaders the “principal agents of change,” functioning as donors, directors and leaders of parachurch organizations. He describes some donors as preferring to bypass the “deliberative democratic process” of church boards to work with parachurch organizations that operate more like modern corporations.100 One result, Lindsay notes, is that it is possible for these leaders to be “religiously active for years without interacting with a poor person in a religious setting.”101

While some parachurch organizations work in coordination with denominations, many can be described as ecumenical, transdenominational, or nondenominational. This has created space for unprecedented partnerships, including between Protestants and Catholics and interfaith alliances between Christians and Jews, for example, as well as alliances with secular entities.