On Tuesday, July 18th, for the first time in ten years, protesters arrived on Dr. Joseph Booker’s block in Jackson, Mississippi. They went door to door, ringing bells and telling people that their neighbor, the state’s last abortion provider, is a baby killer. A few weeks before that, protestors showed up at the Raleigh, North Carolina, home of Susan Hill, the owner of the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the clinic where Booker works. Soon the death threats started coming. “There is a feeling that things are ramping up,” Hill says. “The protestors that we see in various places are more vocal, screaming, not just protesting.” In her experience, clinic violence is often preceded by just this kind of heightened rhetoric.

The last abortion clinic in Mississippi is under siege. In mid-July, Operation Save America—previously known as Operation Rescue—held a week of protests outside the Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The next week, another anti-abortion group called Oh Saratoga! commenced its own seven days of demonstrations. Impatient for a change in the Supreme Court, anti-abortion forces are determined to make Roe v. Wade functionally irrelevant in the state, and they believe they’re getting close

A decade ago, there were six clinics in Mississippi. Yet the combination of constant harassment and onerous regulations led one after another to shut down, and since 2004, Jackson Women’s Health Organization has stood alone. Closing it would be the biggest victory yet in the anti-abortion movement’s long war of attrition. This makes Mississippi an alluring target.

Operation Save America is not what it used to be and on the surface its Mississippi sojourn certainly didn’t look victorious. There were at most a few hundred demonstrators in Jackson. That meant that women coming to the clinic had to brave a gauntlet of shouting people, many holding massive photos of aborted fetuses. But this was a far cry from the days when Operation Rescue brought tens of thousands of protestors to cities like Wichita and Buffalo during the early 1990s, where they tried, and sometimes succeeded, in physically shutting clinics down.

Clinic blockades are far less frequent these days, due largely to both a public backlash and a legal crackdown. Not long after Operation Rescue’s most high-profile demonstrations, a number of abortion providers were murdered, and their deaths sent the militant wing of the movement into disrepute. Then in 1994, partly in response to the killing of Florida abortion doctor David Gunn, President Bill Clinton signed the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act. FACE makes it a federal crime to use “force, threat of force or physical obstruction” to block access to reproductive health services, and imposed prison sentences and fines up to $250,000. The law also allows clinics and health care workers to bring civil suits against violators.

“We’ve been sued for millions and millions of dollars,” says Flip Benham, the head of Operation Save America. A Texan with ruddy, sun-cured skin, and short brown hair, he has the hearty manner of a high school football coach. “Thanks to the media, we’ve been painted with the broad brush stroke of being violent folks because of a few loose cannons, who aren’t even Christian, who blew up abortion mills and killed abortionists. So what happens is, folks are afraid. There are new laws in place now that weren’t there in the 1990s, like FACE.”

The result has been a drastic decline in Operation Rescue’s fortune and its clout. As legal judgments piled up, Benham, who took over the group’s leadership in 1994, changed the group’s name to Operation Save America in an attempt to get out of paying. It didn’t work. “Planned Parenthood came into our office and confiscated every computer, every file, every piece of paper, every pencil that we had,” he says.

Yet Benham and his crew can still make life difficult for reproductive health workers in Mississippi. The protests create a constant, low-level state of emergency among the clinic’s staff, intimidate many of the patients, and add to the tension that plague doctors already living with the omnipresent threat of violence.

Hill owns five clinics throughout the country, and she has to be on constant alert. Over the years, her facilities have been subjected to 17 arsons or firebombings, as well as butyric acid attacks and anthrax threats. One of the doctors who was murdered, David Gunn, worked for her. “Fortunately we’ve been safer in the last few years for whatever reasons,” says Hill. “Thank God there haven’t been the shootings.”

By and large, the people who showed up in Jackson so far are not nearly as belligerent as their rhetoric. Historically, though, the doctors who’ve been targeted by protests—especially protests that demonize them personally—are the most likely to be assaulted or killed by extremists. “All we can say is, when protests at a clinic go up, that’s when there tends to be a shooting,” says Eleanor Smeal, president of the Feminist Majority Foundation. “There seems to be some link.” Many of the abortion providers who have been shot, including George Tiller in Wichita, Kansas, Dr. George Patterson in Mobile, Alabama, Gunn and John Britton in Pensacola, Florida, and Barnett Slepian outside Buffalo, New York, were first the subject of repeated demonstrations and threats. Their names were put on hit lists and wanted posters, and information about them circulated throughout the violent wing of the anti-abortion movement.

Even if the movement’s extreme wing wasn’t represented in Jackson, it has some support there. The most faithful of the Jackson clinic demonstrators is a local man named C. Roy McMillan, who sees protesting abortion as his full-time job and says he’s been arrested 65 times. McMillan is one of thirty-four signatories to a 1998 statement that calls the murder of doctors who perform abortions “justifiable…for the purpose of defending the lives of unborn children.” He describes the late Paul Hill—the murderer of gynecologist Dr. John Britton and his escort, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett—as a friend.

So Dr. Booker has reason to worry. He’s long been one of the gynecologists singled out by militant anti-abortion forces. He’s been stalked repeatedly, and during the 1990s, he was put under the protection of federal marshals. “We were very fearful he was going to be killed,” says Smeal. He had a police escort during the recent protests, but if he’s fearful, he won’t admit it. A 62-year old black man with a trim, white-streaked mustache and goatee, and a stud in his left ear, Booker says anti-abortion harassment has been increasing but he dismisses the protesters as “more bark than bite. If you don’t get intimidated, they get frustrated and don’t show up as much.” A Pittsburgh native who was educated in San Francisco, he describes himself as “a Yankee, pro-choice, outspoken, and black. And that’s a bad combination in Mississippi.”

Race is an omnipresent issue at the protests, though it shows up in unexpected ways. The clinic’s staff and most of the patients are Black; the majority of the protestors are white. Still, the demonstrators see themselves as the heirs of the civil rights movement — they carry pictures of Martin Luther King, Jr., compare the prochoice movement to the KKK and call abortion “black genocide.” What they generally refuse to do, though, is support government measures that might ease the burdens of poverty in the state’s poor, Black communities—or help women better control their reproductive lives. Mississippi’s high rate of unplanned pregnancies, says McMillan, is due to the “moral degeneration of the black culture, and I submit it’s caused by the welfare mentality.”

The protests are just one side of the vise that the Jackson Women’s Health Organization and the women it serves are caught in. Both are also being squeezed by an ever-expanding panoply of antiabortion legislation that’s made Mississippi the most difficult state in America in which to terminate a pregnancy. Even as the Jackson Women’s Health Organization hangs on, the state offers the country’s clearest view of the religious Right’s social agenda in action. It’s a harbinger of what a post-Roe America could look like.

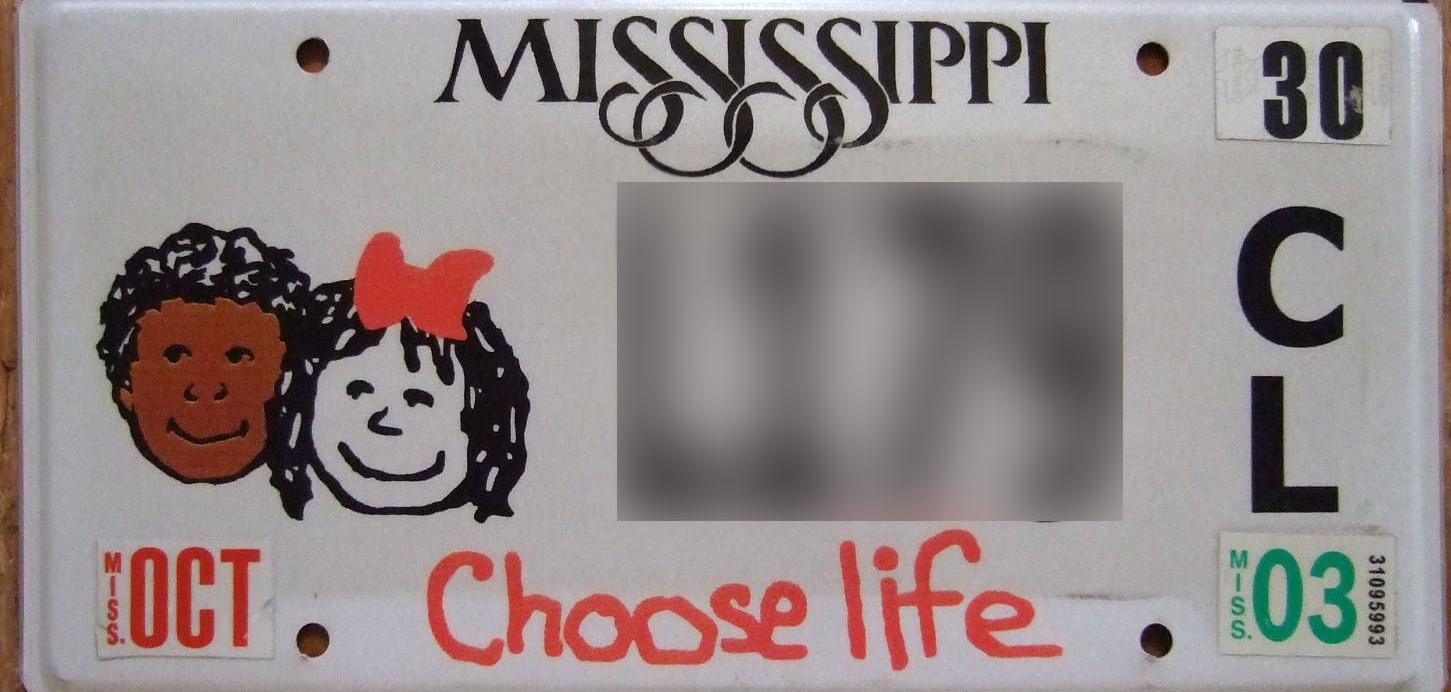

On July 19, a white taxi that says “Choose Life” on its side pulled into the parking lot of the Jackson Women’s Health Center. Out jumped one of the clinic’s surgical technicians. Her boyfriend is a cab driver, and his boss, the owner of Veterans Taxi, has emblazoned the anti-abortion message on every car in his fleet. Opposition to abortion is everywhere in this state—more than an ideology, it’s part of the atmosphere. Recently, Mississippi came close to following South Dakota and banning most abortions; many expect it will do so during the next legislative session. The local government leads the nation in antiabortion legislation. Mississippi is one of only two states in America where teenagers seeking abortions need the consent of both parents, forcing some mothers to go to court to help their daughters override a father’s veto.

Many cars have “Choose Life” license plates; the state gives much of the proceeds from the plates to Christian crisis pregnancy centers. More than two-dozen such centers operate in the state. They look very much like reproductive health clinics, and they offer free pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, but they exist primarily to dissuade women from having abortions. Like other crisis pregnancy centers nationwide, those in Mississippi tell their clients that abortion increases the risk of breast cancer, infertility and a host of psychiatric disorders, none of which is true. And although the women who come to them are virtually all both sexually active and unprepared for motherhood, they also counsel against contraception, believing that abstinence is the only answer for the unwed. At Jackson’s Center for Pregnancy Choices, which gets around $20,000 a year in money from the Choose Life plates, a pamphlet about condoms warned, “[U]sing condoms is like playing Russian roulette…In chamber one you have a condom that breaks and you get syphilis, in chamber two, you have an STD that condoms don’t protect against at all, in chamber three you have a routinely fatal disease, in chamber four you have a new STD that hasn’t even been studied…”

According to Barbara Beavers, a former sidewalk protestor who now runs the Center for Pregnancy Choices, as many as 40 percent of the pregnancy tests the center administer come back negative. Some of the women who take them live with their boyfriends, making a commitment to abstinence unlikely. But Beavers is unapologetic about her opposition to birth control, in part because she thinks a woman whose contraception fails might feel more entitled to an abortion. “They think, it wasn’t their fault anyhow, so let’s just go ahead and kill it,” she says.

Already, places like the Center for Pregnancy Choices are leading public dispensers of reproductive health advice in Mississippi. The schools teach either abstinence or nothing at all. Besides private physicians, the only places that provide birth control prescriptions are the Jackson Women’s Health Organization and the offices of the State Department of Health.

For women seeking to avoid pregnancy, there are other hurdles. According to a survey by the Feminist Majority Foundation, of 25 pharmacies in Jackson, only two stock emergency contraception (EC). Even when the pharmacies do carry EC, individual pharmacists may refuse to dispense it; Mississippi is one of eight states with “conscience clause” laws protecting pharmacists who refuse to dispense contraceptives. Dr. Booker says he has written several EC prescriptions, only to find his patients unable to fill them.

Not surprisingly, Mississippi has the third highest teen pregnancy rate in the country, and the highest teenage birth rate. It is tied with Louisiana for America’s worst infant morality rate. According to The National Center for Children in Poverty, more than half of the state’s children under 6 live in poverty. The immiseration of Mississippi’s women and children isn’t solely the result of diminished reproductive rights, of course. But it’s clear that enforced ignorance and lack of choices play a major role. “You would be surprised what they don’t understand about their own bodies,” Betty Thompson, the former director of the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, says about the clinic’s patients.

For the antiabortion movement, though, Mississippi isn’t lagging behind the rest of the nation. Rather, it’s the vanguard. “We’re not waiting for the president, we’re not waiting for the Congress, we’re not waiting for the Supreme Court to be packed,” says Benham, the head of Operation Save America. “This issue can’t be won from the top down. When you’re on the streets and you see these battles won over and over again, when you see the statistics of abortion dropping, you begin to realize hey, this battle is being won.”

Indeed, the same strategy at work in Mississippi is being used all across the country. According to the National Abortion Federation, 500 state-level anti-abortion bills were introduced last year, and 26 were signed into law. The number of abortion providers dropped 11 percent between 1996 and 2000, and almost 90 percent of U.S. counties lack abortion services.

Abortion rights won’t disappear in America in one fell swoop, and they can’t be protected by a single Supreme Court precedent. Congress’s ban on adults taking a minor who is not their child across state lines for an abortion, and South Dakota’s attempt to ban abortion outright, are making headlines. But the more gradual erosion of rights often escapes people’s view. Through a combination of militant street actions and punitive legislation, Roe v. Wade is being hollowed out from the inside. The right to an abortion doesn’t mean much if there’s no way to get one.